By Joseph Young

For casual observers, the recent dust-up over the delisting of the Mujahedeen-e-Khalq, or MEK, from the State Department’s Foreign Terrorist Organization (FTO) list may seem a bit like much ado about nothing. However, the debate provides a good opportunity to assess this list, how it is made, and what it should be. Importantly, why have such a list? What is its purpose?

The list is at its core a legal distinction. To qualify for potential inclusion, a group must be foreign, they must engage in terrorism as defined by the US State Department, and the group must threaten the US, its citizens, and/or its interests.

There are three immediate implications of being placed on the list:

- It provides legal justification for prosecuting someone who provides support or trains with any of these groups.

- It allows the US to deport or keep out any group member or affiliate.

- It establishes the power of the US Department of Treasury to freeze assets associated with the group.

How then does a group get on the list? The list currently has about 50 groups (give or take a few). Recent large studies of terrorist organizations list the existence of at least 600+ to over 2,200 groups that employed terrorism since the late 1960s or early 1970s. It is fair to assume that not all of these hundreds of groups threaten US interests, but 50 is surely an underestimate. Given this fact, it is quite likely that not all groups that fit the State Department’s criteria are on the list. As a side note, it is unclear what threatening US interests actually is when our interests can be very broadly defined. If we take it at the most basic definition — a group that is likely to target US citizens — again 50 seems too small. So why is the list incomplete?

As I previously argued, labels matter as they help us group alike things and hopefully explain the world a little better. The FTO list and the FTO label should help identify potential threats and give the USG the necessary tools to intervene. Instead it feels like an arbitrary tool that can be updated or amended based on the current political climate.

Related, there was also a good deal of hand-wringing over whether to include the Haqqani network, a group closely allied with the Pakistani intelligence agency, the ISI, on the list. While there is little debate over whether this network actually uses terrorism, the concern is how Pakistan will respond to the designation. “One man’s terrorist group is another man’s drug-running, al-Qaeda linked, Taliban supporting militant organization?”

Let’s reform the list. Let’s include all foreign groups that use terrorism. Let’s take groups off the list that don’t use terrorism or have renounced this form of violence. Make this a list that is based on a consistent application of the letter and spirit of the law and that is a tool for reducing violence and not a tool for rewarding or punishing groups for political purposes.

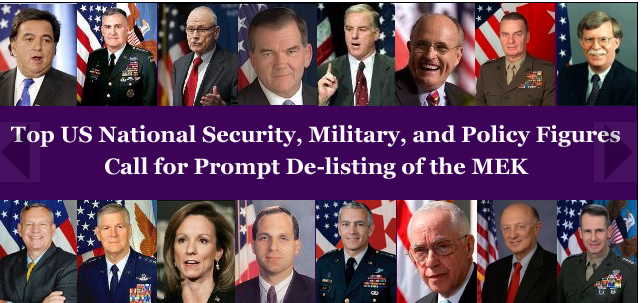

Image taken from the DeList MEK website.

1 comment