By Steven T. Zech for Denver Dialogues

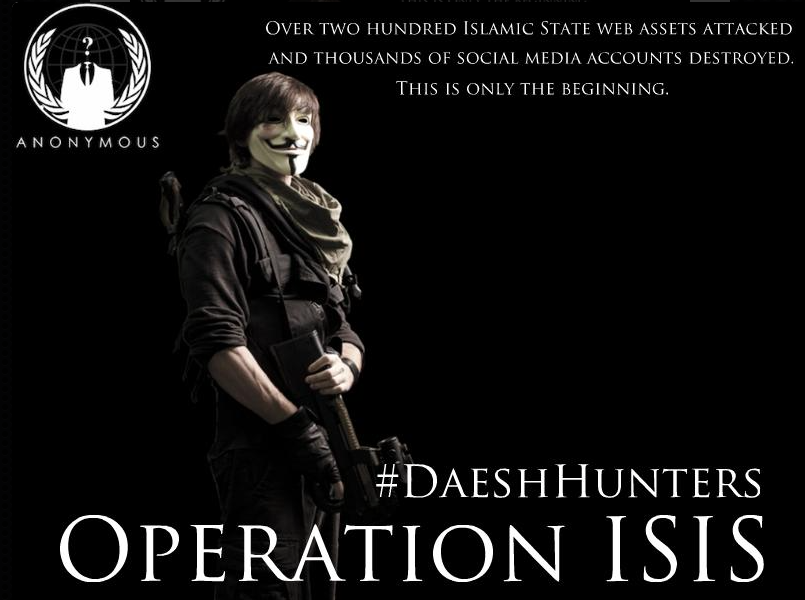

This past month the “hacktivist” collective known as Anonymous intensified its cyber-attacks against the Islamic State. Anonymous affiliates (or “Anons”) coordinated with other hacker groups to identify and track online support for the Islamic State. Over one hundred hackers helped to compile and release a list of thousands of Twitter account names as part of #OpISIS, a campaign to disrupt the Islamic States’ virtual presence. What is Anonymous? Why are its affiliates targeting the Islamic State? And is it a good idea?

The many faces of Anonymous

Anonymous is a hacker collective that dates back to 2004. Academics and journalists have described Anonymous as a “shape-shifting subculture” or a “series of relationships,” rather than an organization or unified movement. Anonymous affiliates include both “merry pranksters” and sophisticated social advocacy networks. Its ranks have taken action against targets ranging from the Church of Scientology, for perceived efforts at censorship, to large financial services companies like MasterCard, Visa, and PayPal, for complicating donation efforts to WikiLeaks at the behest of the U.S. State Department. Other examples of Anonymous operations include support for large-scale social movements in Tunisia, Libya, and Egypt.

Some operations demonstrate the contested nature of the Anonymous label. For example, in Ferguson, Missouri some Anonymous elements organized a “National Day of Rage” that sought to overshadow a previously planned protest calling for a “National Moment of Silence.” In another case a group of hackers claiming to operate under the Anonymous banner released a video threatening Israel with an “electronic Holocaust.” Significant differences in priorities and ideological tenants exist among those who claim affiliation. In an online YouTube video, a Guy Fawkes mask explains:

You cannot join Anonymous. Anonymous is not an organization. It is not a club, a party, or even a movement. There is no charter, no manifest, no membership fees. All we are is people who travel a short distance together, much like commuters who meet in a bus or tram. For a brief period of time we have the same route; share a common goal, purpose, or dislike; and on this journey together we may well change the world. Nobody could say you are in or you are out.

“Anons” come from all religious, ethnic, and socio-economic backgrounds. Both men and women (i.e. “Anonymisses”) have joined Anonymous operations. Supporters do not act on behalf of a particular nation, nor do they have fixed objectives.

A convergence of interests: From cyber-terrorist threat to (potential) ally

In early 2012 the director of the NSA warned of Anonymous’ growing capabilities and the potential for disruptive attacks against the United States. A genuine fear that Anonymous might have the ability and desire to target the American power grid seemed to take hold within the U.S. government. Many involved in U.S. defense worried that this loose network of technologically savvy civilians might constitute a real threat to national security. However, in light of recent actions against Islamist militants by hackers operating under the Anonymous banner, these fears seem to have subsided.

A tacit alliance appears to have developed between numerous Western states and several Anonymous affiliates based on a shared interest in combating militant Islamist groups. Anonymous began strikes against the Islamic State after a wave of beheading videos appeared on the internet last year and it targeted suspected proponents of Islamist terrorism more frequently after the attack on the Paris headquarters of Charlie Hebdo in January 2015. One Belgium-based group vowed to fight for the “inviolate and sacred right to express opinions in any way” after the Paris attacks and started to target accounts on social networking sites linked to Islamist terrorism. Anonymous affiliates prepared operations aimed at Islamist militants and their supporters, largely driven by moral repugnance.

The cyber collective initiated its latest round of offensive operations several days before U.S. president Barack Obama asked Congress to authorize the use of military force against the Islamic State on February 11, 2015. Anonymous took down Twitter handles tied to Islamic State supporters and generated a list of Facebook pages that should be monitored. The hacker collective released a statement that, “The terrorists that are calling themselves Islamic State (ISIS) are not Muslims!” Anonymous promised the Islamic State that, “We will hunt you, take down your sites, accounts, emails, and expose you. From now on, no safe place for you online. You will be treated like a virus, and we are the cure.”

Anonymous continues to release statements with updates related to #OpISIS. After their latest round of take-downs, participants explained the need to raise more awareness about the long list of social media accounts they identified:

The more attention it gets the more likely it becomes Twitter takes action in removing these accounts and making a serious impact on the ability of ISIS to spread propaganda and recruit new members. You don’t have to be tech savvy to contribute, simply clicking retweet or like could mean the difference between almost 10 thousand active accounts or 10 thousand suspended ones. Help us fight.

The goal of Anonymous is to pressure Twitter into removing more accounts linked to Islamic extremism. Twitter has taken action against many accounts, but remains uncertain how to proceed. Twitter co-founder and his employees have received threats that Islamic “lions” would be coming for them in response to their meddling. This case provides an interesting example of the important interactions among civilian activists, government, and businesses, as each plays a role in confronting security challenges tied to religious extremism.

The pros and cons of Anonymous support

In a recent interview, the U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations, Samantha Power, identified crucial factors that should compliment a U.S.-led air campaign in Iraq and Syria. Humanitarian assistance must reach the hundreds of thousands of displaced people that have fled territory now under Islamic State control. Governments should bolster border controls and strengthen legal tools to reduce the influx of foreign fighters. Finally, a comprehensive strategy must include a stronger counter-presence on social media. Could Anonymous provide additional assistance on this front?

Limiting the Islamic State’s ability to share its vision and disseminate directives is a key part of any strategy aimed at halting its expansion. However, U.S. efforts to stop Islamic State propaganda and to generate a convincing and coherent counter-narrative have found little success. Anonymous may succeed where some government offices have not (e.g. the State Department’s Center for Strategic Counterterrorism Communications). In a recent Foreign Policy article, Emerson Brooking argues that the U.S should provide greater support for Anonymous affiliates already combating the Islamic State, perhaps putting them on the government payroll or offering Bitcoin bounties. Increased pressure would push the Islamic State deeper into the web, hindering its communication and coordination capacity. Enabling tech-savvy civilians to attack the Islamic State’s web presence may help to minimize the communicative effects of civilian beheadings and other acts of counter-normative violence. A “cyber-militia” could help to address many of the new technological challenges faced in 21st century armed conflicts.

Alternatively, Anonymous support could prove detrimental to state efforts to combat the Islamic State. Some reports suggest that government investigators would actually prefer that the accounts stay up. Removing virtual trails to suspected militants could hinder investigators’ ability to gather intelligence, map out communication networks, and track down operational cells. For example, one intelligence expert who follows Islamic State tweets described five foreign-born fighters communicating openly over Twitter about a planned meeting in a Syrian cafe. By monitoring, instead of removing accounts, intelligence practitioners can glean information about potential threats to improve existing counterterrorism efforts. Policymakers must evaluate the trade-offs between limiting propaganda and coordination and hindering intelligence collection.

Anonymous interventions may also generate unintended negative consequences, as they have in previous operations. For example, Anonymous affiliates misidentified the person responsible for the shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson. When Anonymous affiliates got involved in a case where two teens sexually assaulting a young girl in Ohio, their actions accidentally revealed the identity of the victim to the public. There is no accountability in place for the allegations and actions of Anonymous activists targeting suspected Islamist militants and those sympathetic to their cause. Without coordinating with investigators and the intelligence community, an Anonymous activist might disrupt an ongoing operation or spark retaliatory actions by the Islamic State.

Ultimately, policymakers must remain mindful of how increased civilian participation could introduce new challenges in the fight against the Islamic State. The involvement of businesses like Twitter in efforts to combat violent extremism complicates policymaker decision-making. Furthermore, cases of direct civilian participation in combat operations have raised important questions about the legality and desirability of involving non-state actors in violent conflict. While the U.S. government has taken steps to keep its former soldiers from joining the ranks of Kurdish security forces, its stance on cyber activism remains ambiguous. Anonymous’ participation might provide an additional tool in the struggle against the Islamic State and violent extremism, but the effects of its participation remain unclear.

7 comments

Reblogged this on The World Around Us.

The purposes of a loose group of anarchists like Anonymous, although doubtless well infiltrated, must be generally very much at variance with the purposes of an imperial state, except by accident. Accidents will no doubt abound, since the imperial state in question, or its satellites, seem to have founded and armed the Islamic State, but they probably cannot be depended upon to the full satisfaction of either party.

it’s the “conscience” at work.

This is a really interesting article – thank you.

I also feel counter presence is important to tackle this issue, by sitting back we are actually loosing hold on bringing up peace to the world..