Guest post by Jennifer M. Dixon

Last Friday marked the 100th anniversary of the Armenian Genocide. The anniversary was a focal point for commemoration and activism, and ratcheted up pressures on Turkey and others to recognize the genocide as such. As the date approached, a flurry of new books was published, and so many academic conferences were convened that experts on the genocide declined many invitations and yet still had an exhausting and stimulating past few months. At the political level, countries such as the United States and Germany were faced with renewed pressures to recognize the genocide, while the Turkish government sought to minimize criticisms of its narrative of the “Armenian question” (Ermeni sorunu). (On the Turkish government’s efforts along these lines, see here, here, and here.)

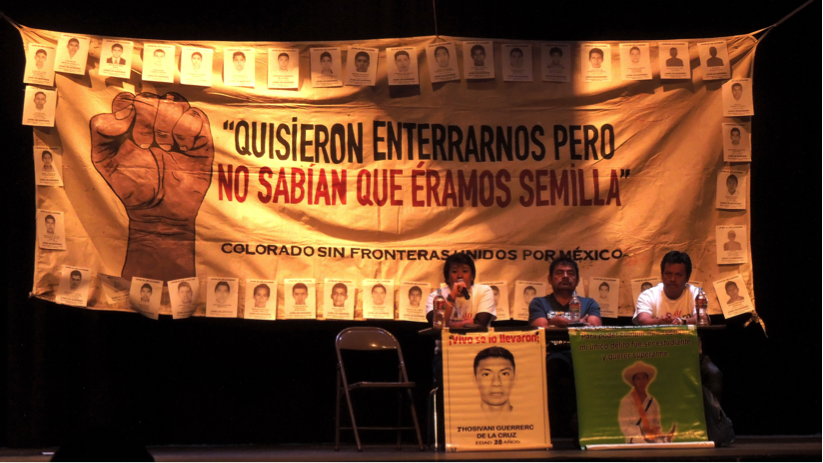

In the end, the anniversary prompted some important shifts. The most notable were Pope Francis’ recognition of the genocide, the German Federal President Joachim Gauck’s remarkable acknowledgement of the genocide and Germany’s share of responsibility in it, and the unprecedented set of coordinated protests and commemorations organized in Istanbul by Turks and Armenians from Turkey and around the world.

And yet, despite this heightened scrutiny, Turkey’s position did not change. On the one hand, the Turkish prime minister Ahmet Davutoğlu offered “deep condolences” to the descendants of “the innocent Ottoman Armenians who lost their lives.” However, statements by President Erdoğan and other officials conveyed a very different impression. For example, President Erdoğan declared: “It is out of the question for there to be a stain or a shadow called genocide on Turkey.” Similarly, the Turkish Foreign Ministry issued a press release condemning the European Parliament’s resolution acknowledging the genocide as a mistaken repetition of “the anti-Turkish clichés of the Armenian propaganda.” Taken together, these and other statements were largely consistent with Turkey’s narrative over the past decade.

This lack of change in Turkey’s position – while relatively unsurprising – raises two questions. First, why has Turkey been so reluctant to acknowledge that what happened from 1915-17 was a state-organized genocide? And second, when and why do states change the stories they tell about dark pasts such as this?

My own comparative research into the trajectories of Turkey’s narrative of the Armenian Genocide and Japan’s narrative of the Nanjing Massacre offers answers to these questions.[1] Comparing across these two cases, I have found that the higher the perceived costs of acknowledgment, the less likely a state is to change its narrative.

In Turkey’s case, the perceived costs of acknowledgement are quite high. Officials have long worried that acknowledging the genocide could expose the state to demands for territory and compensation, and could undermine the legitimacy of the founding narrative and key political institutions in Turkey. These material concerns were made clear in a 1990 speech by the Turkish prime minister, Yıldırım Akbulut. In the speech, he explained that “leaders of Armenian communities … have declared … at every opportunity that these resolutions will constitute the basis for their future claims for compensation and territory. … In view of these facts, Turkey has come to the conclusion that efforts to make the international community accept and confirm the so-called Armenian genocide must be stopped. … Consequently, it is out of the question to make concessions from our fundamental position.”[2] Despite the fact that territorial claims are unlikely to gain traction in the post-World War II international system, this concern continues to be central for Turkish officials. (For other scholars who make this point, see Akçam, Ulgen, and Ulgen again.)

Concerns about national identity have further deepened the perceived costs of change. The heroic story of Turkey’s founding is premised on the silencing of the genocide and ethnic cleansing that immediately preceded its birth. The founding narrative presents the establishment of the Turkish Republic as a historical juncture that broke with the Ottoman past and created a completely new nation and state. The genocide, however, belies this purported break. The wealth of the new state was based on properties expropriated from Armenians, and the Muslim and Turkish identity of the new nation was made possible by the violent homogenization of the population.

In spite of these strong constraints on change, Turkey’s narrative has shifted somewhat over time. From 1930 through the late-1970s, Turkey’s narrative denied and silenced what had happened to Ottoman Armenians. Starting in 1981, however, the official narrative shifted to include references to the events, but ones that largely involved mythmaking and relativizing Armenian deaths. Beginning in 2001, the state’s narrative came to acknowledge basic facts about the deportation and deaths of Armenians, while at the same time more strongly relativizing those facts.

What explains these changes? My research indicates that sustained international pressures – especially from powerful states – increase the likelihood of change in states’ narratives of dark pasts. Such pressures can challenge the domestic legitimacy of an official narrative and alter the cost-benefit calculus underlying it. Crucially, however, the timing, content, and direction of change are often contingent on domestic political considerations and dynamics.

Thus, a series of terrorist attacks on Turkish diplomats and the beginnings of international recognition of the Armenian Genocide – both in the 1970s – eventually led Turkish officials to break their silence on the issue in 1981. However, when and how they did were shaped by Turkish officials’ abiding concerns and by domestic constraints on discussion of the issue. When Turkey’s narrative again changed in 2001, the triggers were an accumulation of states recognizing the genocide. And yet, as before, the substance of Turkey’s narrative was shaped by domestic discussion of the issue, international normative expectations, and institutionalized interests within Turkish politics.

What do these insights say about the events of the past week? On the one hand, it is clear that the centenary of the Armenian Genocide was an important focal point for protests, commemorations, and renewed discussion of the genocide and its legacy. That said, states’ narratives are “sticky” institutions that change slowly. Thus, to have expected this anniversary to prompt significant changes in Turkey’s narrative, even for an event that is now one hundred years in the past, was unrealistic. Nevertheless, given the importance of international pressures in changing incentives and considerations over the long term, the acknowledgements and transnational activism catalyzed by the anniversary do hold the potential for change in the future.

Jennifer M. Dixon is an Assistant Professor of Political Science at Villanova University.

[1] I define an official narrative as a state’s characterization of an event, including the nature and scope of the event, and the state’s characterization of the role and responsibility of government officials and institutions in the event.

[2] Ankara TRT Television Network, “Akbulut, Party Leaders Address National Assembly: Akbulut Speaks on U.S. Ties,” 21 February 1990, translated and published in FBIS, Daily Report: West Europe, FBIS-WEU-90-037 (23 February 1990), p. 21.

4 comments

Reblogged this on tamarlomidze.

Dear Jennifer, Do you have any idea why Ottoman Empire did not kill them in their land but deported them hundreds miles south to another Ottoman land?

Good article and a good perspective. BUT, why does every historical account omit the 1919 war crimes trial held in Turkey which convicted the 3 architects of the Armenian genocide of a crime and sentenced them ???? It’s a glaring omission from almost all of the coverage. I’m saying the new Turkey convicted the old Ottoman Empire rulers and this was in a Turkish Court. We need to change the narrative from “they’ve always denied it” to the fact that somewhere along the line Turkish courts acknowledged that it was a Crime Against Humanity. And then subsequently decided on the policy of a systematic cover-up of that fact. They still have a century of acknowledgment to go, but I think the Turkish people would be interested to know that historically the government, at least early-on, did the right thing.

Hi Cindy,

Thanks for your comment. It is true that, between 1919 and 1920, trials of a small number of Ottoman officials accused of participating in the genocide were held in Constantinople. These trials were organized and conducted by the Ottoman government, however. The Republic of Turkey (i.e., today’s Turkey) was not established until 1923.

For more on these trials, see:

Gary Jonathan Bass, Stay the Hand of Vengeance: The Politics of War Crimes Tribunals (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2000).

Vahakn N. Dadrian, “The Turkish Military Tribunal’s Prosecution of the Authors of the Armenian Genocide: Four Major Court-Martial Series,” Holocaust and Genocide Studies, vol. 11, no. 1 (1997), pp. 28–59.

Vahakn N. Dadrian and Taner Akçam, eds., Judgment at Istanbul: The Armenian Genocide Trials (New York: Berghahn Books, 2011).

Alan Kramer, “The First Wave of International War Crimes Trials: Istanbul and Leipzig,” European Review, vol. 14, no. 4 (2006), pp. 441–55.

–Jennifer