By Erica Chenoweth for Denver Dialogues

On Sunday, the Monkey Cage ran a piece by Matthew Baum and Phil Potter suggesting that the policy of “democracy-promotion” has gone out of style.[1] I think they’re right that in many circles democracy-promotion is politically passé and that, more broadly, democracy advocates are really having a tough couple of years. In the midst of pushback against democracy agendas within democracies themselves, they are also dealing with the “comeback” of authoritarianism. [2] Setting aside the debate as to whether the recent resurgence is overstated, it does appear to be the case that while democratic countries are questioning the wisdom of promoting republics abroad, authoritarian regimes are pushing back against civil society, activists, and oppositionists, seeing them as a direct threat to their established orders.

In May, the Korbel School had the pleasure of hosting one of the world’s foremost thinkers on this topic, Maria J. Stephan (Senior Policy Fellow at the U.S. Institute of Peace, Senior Fellow at the Atlantic Council, and my sometimes co-author) as a practitioner-in-residence. In some of her recent work, she articulates a nuanced rebuttal to democratization skeptics. While she was in town, we hosted a launch event for her co-edited (with Mat Burrows) book, Is Authoritarianism Staging a Comeback? You can watch the full video here.

We didn’t have time during the event to get to all of the questions I wanted to ask, so Maria graciously agreed to expand upon her views in writing. Here’s what we discussed:

Chenoweth: Recently, democracy-promotion and the good governance agenda have been getting a lot of flack. In recent weeks, Gordon Adams skewered the State Department’s quadrennial report for its focus on democracy-promotion in Foreign Policy Magazine, and Stewart Patrick & Isabella Bennett wrote an article with the blunt title “Geopolitics is Back—and Global Governance Is Out” in The National Interest. Lots of people are saying, “Look around—the world is falling apart. Stop talking about democracy and start talking about restoring global stability and order.” So why should democracy-promotion still be on top of the U.S. foreign policy agenda?

Stephan: Well, I’m not sure if the world is falling apart. But it is precisely because bad governance is fueling protracted violent conflict around the world that support for democratic development should be atop the US foreign policy agenda. We know historically and empirically that democracies don’t tend to go to war with each other. They tend to be better governed, have institutions and mechanisms for resolving conflicts peacefully, and make more reliable strategic partners. Furthermore, the credibility of the U.S. is enhanced globally when we are seen to advance values of dignity, human rights, and democratic freedoms that so many ordinary people around the world risk life and limb every day to defend.

The question should not be whether the U.S. should support democratic development—including here at home. The question should be how to do it more consistently and effectively. Notably by standing behind local democrats, by discouraging governments from responding to nonviolent challenges using violent force and repression, and by making long-term investments in civil society and democratic institutions. Fortunately, the new Quadrennial Diplomacy and Development Review (QDDR), the strategic roadmap for the U.S. State Department and USAID, mentions good governance and accountability over fifty times and makes the point that good governance underpins all other strategic priorities. It’s time to have a robust conversation about what that means in practical terms.

Chenoweth: Why is authoritarianism making a comeback?

Stephan: There’s obviously no single answer to this. But part of the answer is that democracy is losing its allure in parts of the world. When people don’t see the economic and governance benefits of democratic transitions, they lose hope. Then there’s the compelling “stability first” argument. Regimes around the world, including China and Russia, have readily cited the “chaos” of the Arab Spring to justify heavy-handed policies and consolidating their grip on power. The “color revolutions” that toppled autocratic regimes in Serbia, Georgia, and Ukraine inspired similar dictatorial retrenchment.

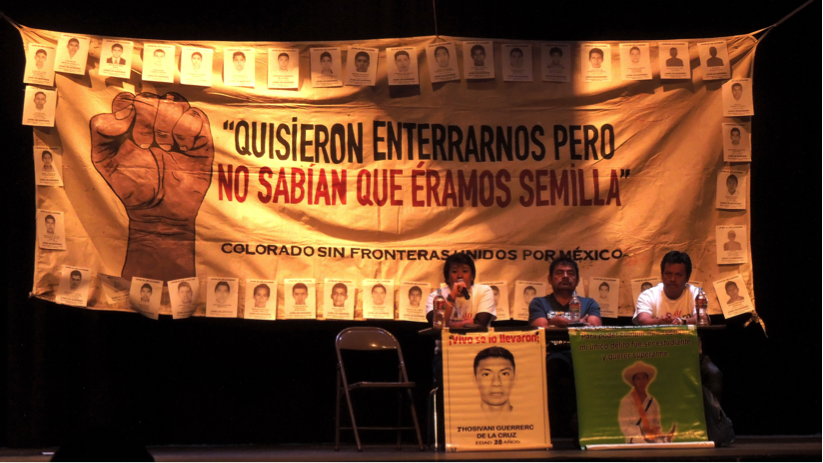

There is nothing new about authoritarian regimes adapting to changing circumstances. Their resilience is reinforced by a combination of violent and non-coercive measures. But authoritarian paranoia seems to have grown more piqued over the past decade. Regimes have figured out that “people power” endangers their grip on power and they are cracking down. There’s no better evidence of the effectiveness of civil resistance than the measures that governments take to suppress it—something you detail in your chapter from my new book.

Finally, and importantly, democracy in this country and elsewhere has taken a hit lately. Authoritarian regimes mockingly cite images of torture, mass surveillance, and the catering to the radical fringes happening in the US political system to refute pressures to democratize themselves. The financial crisis here and in Europe did not inspire much confidence in democracy and we are seeing political extremism on the rise in places like Greece and Hungary. Here in the US we need to get our own house in order if we hope to inspire confidence in democracy abroad.

Chenoweth: We are seeing a dip in the effectiveness of civil resistance. Why do you think this is the case? Why are governments getting better at repression, and why are movements making more mistakes today than before?

Stephan: Good question. The global diffusion of people power movements has surely inspired activists living under repression in different parts of the world. Activists boast remarkable courage but one problem is that they often lack the skills to wage nonviolent struggle strategically, and for longer than a few weeks or months. According to our research, the average nonviolent campaign takes 3 years to run its course. Most activists do not plan for three year’s worth of tactical sequencing, communicating a viable alternative, broadening and deepening the levels of participation, prompting loyalty shifts in the regime’s key pillars, etc. I think this problem is exacerbated by over-reliance on social media, which is facilitating rapid connections and communication—all great—but oftentimes thrusting activists and their movements into primetime before they are sufficiently prepared and organized.

Furthermore, regimes often have huge amounts of resources to dedicate to cyber-suppression, to usurping complete control of the media, co-opting real or potential dissent, preventing fraternization by security forces, and frightening people into supporting the status quo. With the exception of a few brutal leaders in Syria, North Korea, and Uzbekistan, most authoritarians can rely on a “velvet fist” to control populations and suppress dissent. They don’t need mass violence.

Activists are forced to operate in fluid, quickly changing environments. They often lack access to key pieces of information while their movement is ongoing, making it difficult to evaluate what’s working and what’s not and adapting their strategies and tactics accordingly. Their heavily resourced, patient, regime opponents are simply out-performing and out-maneuvering them in many cases.

Chenoweth: What are the ways that dictators are learning? How do we know they are learning?

Stephan: Authoritarian regimes have a learning curve and they are clearly adapting their strategies and tactics. Scholars like you, Steve Heydemann, Daniel Brumberg and Regine Spector have done excellent research on this topic. There are many similarities in regimes’ responses to nonviolent movements, as you note in your chapter on the “Dictator’s Playbook”: they blame opposition activities on outsiders; they characterize the opposition as traitors and terrorists; they coopt the opposition through legislative reforms; they pay off their inner entourage; they counter-mobilize their own supporters; they employ agents provocateurs to foment violence in the ranks of the opposition; they outsource repression to thugs; they master the art of censorship and surveillance; they keep journalists out; they use pseudo-legitimate laws to keep their grip on power; and they assemble a coalition of allies to share techniques and tactics.

We are seeing regimes literally copying legislation (sometimes verbatim) from each other to outlaw civic activity and prevent foreign funds from reaching domestic NGOs. They are investing heavily in cyber-surveillance technologies in order to disrupt democratic organizing. They are bringing in police and security forces from foreign countries, as the Bahraini government does, to discourage fraternization with protestors and to reinforce sectarian divisions. It’s remarkable how systematic their strategic adaptation is. In many cases, they are way ahead of pro-democracy activists.

Chenoweth: What is being done to support democracy? By whom? What further actions can be taken to support democracy?

Stephan: In an era of closing space for civil society and authoritarian retrenchment—both major threats to international peace and security—we need to get serious and innovative about supporting democratic development. External support should be sensitive to the needs and security concerns of local democrats. We should learn from mistakes of the past. For example, we know that “imposing” democracy via military coercion doesn’t work and that focusing excessively on the procedural aspects of democracy, like elections, is insufficient.

Support for democratic development must be a long-term strategy for governments and non-governmental actors, and include sustained support for inclusive institutions, rule of law, countering corruption, and support for civil society. The Diplomat’s Handbook for Democracy Development Support offers a range of tools that diplomats and embassies can use to support civil societies and democratic transitions. Meanwhile, Military Engagement: Influencing Armed Forces Worldwide to Support Democratic Transitions shows the under-appreciated leverage that militaries have to influence the attitudes and behaviors of soldiers and officers in non-democratic societies. There are many tools that governments and non-governmental actors have to support anti-corruption efforts, which is a necessary ingredient to preventing backsliding.

I see much potential in the Obama administration’s Stand With Civil Society initiative. Launched two years ago, this initiative calls for coordinated international activity in three areas: creating a legal enabling environment for civil society; coordinating diplomatic pressure when governments impose unreasonable restrictions on civil society; and developing new tools and platforms to support civic actors. As part of this initiative, USAID, together with the Swedish International Development Agency (Sida), Agha Khan, and Open Society Foundations, has launched the Civil Society Innovation Initiative. CSII will create regional “hubs” for civil society to bring together closed and open spaces, traditional and non-traditional civil society actors, and governments and civil society. The U.N., which has a Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Freedom of Peaceful Assembly and Association, is increasingly taking the issue of closing spaces seriously. So there is definitely momentum to do something about the global threat to democracy.

My hope is that external actors increasingly embrace a movement mindset and develop flexible means to support non-traditional civil society actors who are in the best position to mobilize people around shared democratic goals. Money matters, particularly when it takes the form of core support to credible local civic actors, as the National Endowment for Democracy and Open Society Foundations have typically provided. But nobody wants to create a marketplace for activism.

Possibly more important than money is for external actors to provide the platforms and convening spaces for activists to learn from each other, to access resources and training materials about strategic nonviolent action, and to provide sustained mentoring. Organizations like Rhize, the U.S. Institute of Peace, and the International Center on Nonviolent Conflict are key actors in in this space. University programs, like the Korbel School, are in a position to provide timely analyses about the closing space phenomenon and generate data that could be useful for activists and policymakers alike.

[1] This is puzzling given the well-demonstrated fact that successful democratization brings relatively more peaceful, stable times to the international community. They suggest that institutional checks protecting whistleblowers and robust, independent media are the main institutional ingredients leading to peaceful democratic behavior. Ultimately, Baum and Potter argue that when it’s done right, democracy-promotion that reinforces these crucial institutions can ultimately stabilize and reinforce peaceful world orders. [2] It’s not settled that authoritarianism is actually on the march, but much of the disagreement stems from definitional and measurement issues

5 comments

Reblogged this on Chrisy58’s Weblog and commented:

I found this article this morning, and am posting it with this article. Is this true?

Reblogged this on bossogwo.

An excellent discussion, with great links. In line with the Diplomat’s Handbook, you might check out the last chapter of my book on democratization NGOs, which has a 12 step program international actors trying to promote democratization. For more see http://www.importingdemocracy.org

It is interesting to see the praise for USAID and the State Department. The role of these agencies in the world is actually a key reason as to why people are losing faith in democracy and why resistance movements are failing. More people and governments see the US is behind many of these color revolutions. While the US says it is acting to bring democracy to countries (Woodrow Wilson used this language to get the US into World War I), in fact they are acting for the geopolitical interests of the United States. Bringing democracy is often cover for the US starting a war.

The Ukraine is an excellent example, where according to US State Department official, Victoria Nuland, the US spent $2 billion to build “civil society” – code for opposition to the Russia leaning government; where she, Sen. McCain and the US ambassador joined the protests in the street. Now Ukraine is a mess and has become a pawn in the US conflict with Russia. The Ukraine government is dominated by the US, Petro Poroshenko the president, is described in leaked State Department Cables as a US informant going back to 2006, Prime Minister Arseniy Yatsenyuk was picked by Newland in a leaked telephone call as her first choice for leader of the country, Natalie Jaresko, is a US born State Department official who was made a citizen of Ukraine by the president on the day she became Finance Minister. Vice President Biden’s son and a John Kerry fundraiser were put on the board of the largest energy company. The coup put in place a US government that is being directed to conflict with Russia for the purposes of US foreign policy.

Venezuela is another example, the US is working with oligarchs “to bring democracy” to a country that is one of the most democratic on Earth. These phony revolts have failed because the country knows the truth about their country and is not falling for US supported revolts.

In Hong Kong, you can find the hands of the US National Endowment for Democracy supporting the protesters, undermining their credibility with the public.

There are numerous examples, so why is resistance failing? It is failing because it has become a tool of US Empire and hegemony. If is bizarre to see praise for USAID which has such a long history as a CIA front and has itself acted to intervene into the internal affairs of countries all over the world in order to cause regime change, when the US does not like the government.

Why is US inspired democracy failing because people, including the vast majority in the United States, understand that US democracy has become a mirage, with rigged elections and elected officials who act on behalf of the wealthy, not the people. If the US wants to spread democracy it would be best to do so by example, fix democracy at home, empower people to make decisions with direct democracy programs like participatory budgeting, encourage democracy in the workplace with worker co-ops where workers make decisions and encourage local assemblies where communities can decide their future. The US has a lot of work to do in creating a real democracy. The US should focus on ixing its internal problems rather than spreading false democracy around the world through wars and color revolutions.