Guest post by Michael Kenney.

Today, two of Britain’s leading extremists go on trial at the historic Old Bailey courthouse in London for allegedly encouraging their followers to support the “Islamic State” in Iraq and Syria. Both men, Anjem Choudary and Mizanur Rahman, are long-standing leaders of the activist network formerly known as “al-Muhajiroun,” which has radicalized hundreds of young men and women into violent extremism since the late 1990s. While the network specializes in organizing inflammatory demonstrations that generate widespread media attention, a number of former associates have been implicated in acts of political violence, within and outside Britain. In recent years, Her Majesty’s counter-terrorism authorities have cracked down on al-Muhajiroun, arresting its activists, outlawing its spin-off groups, and convicting its leaders of crimes related to their activism. This latest trial grows out of a series of police raids targeting network leaders in September 2014, after British officials grew increasingly alarmed about the flow of young citizens to Iraq and Syria to join the newly-declared “Islamic State.” Indeed, one of those arrested in the roundup later escaped Britain with his young family and fled to Syria, where he has since emerged as a leading ISIS propagandist. Back in Britain, al-Muhajiroun has not only survived the crackdown, it has continued its activism. In a new article from the Journal of Conflict Resolution, my co-authors and I explain why.

Applying network analysis to an original dataset of 3,000 news reports on al-Muhajiroun and over eighty interviews with network activists between November 2010 and December 2014, we argue that al-Muhajiroun adapted to government pressure by evolving from a “scale-free-like” network centered around its original “emir” to a more decentralized, “small-world” network featuring multiple leaders who linked different groups or “clusters” of local activists. This structure allowed activists to continue their efforts through two mechanisms. First, the network’s small-world configuration provided multiple connections between clusters that allowed activists to share information and other resources, even when leading activists were removed through police pressure. Second, within the clusters, which often take the form of neighborhood-based study circles or “halaqahs,” activists interacted frequently, coordinated their activities, and recruited new members to replace participants who left the activist network. Al-Muhajiroun’s “small-world-ness” allowed it to survive the departure of previous leaders, including its founder and original “emir,” and will likely do the same should Choudary and Rahman be convicted of providing support to ISIS.

The policy implications of al-Muhajiroun’s transformation are readily apparent. At the most general level, it reminds us that when states engage in “counter netwar” the pressure they exert on their adversaries can have profoundly unintended consequences. In both the war on drugs and the war on terror, government attempts to destroy the largest, most successful illicit networks did not end or even severely disrupt the supply of either transnational commodity. Instead, it led to the decentralization of both as smaller, harder-to-eliminate adversaries emerged to replace the drug “cartels” and terrorist “kingpins” who preceded them. Similarly, al-Muhajiroun responded to state pressure by decentralizing into a more diffuse, small-world form. This structure proved more resistant to the state’s targeted attacks than the scale-free form it assumed during its early years.

The al-Muhajiroun of today is unlikely to be destroyed by the removal of one or two highly connected leaders, including Anjem Choudary and Mizanur Rahman. This suggests that a strategy of leadership decapitation against the activist network will not prove particularly successful. The best authorities can hope to achieve through such an approach is temporary disruption, as targeted activists are replaced by others outside the government’s plan of attack. This finding has implications for other “dark networks.” Recent studies have shown that killing the leaders of underground enterprises often does not work. Instead of eliminating these networks, targeted killings can lead to their revitalization, as other leaders emerge to replace decapitated nodes.

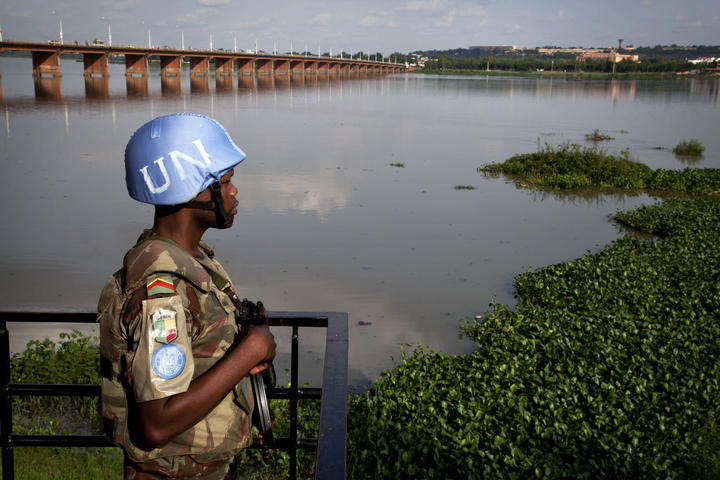

Al-Muhajiroun’s small-world solution has additional implications for dark networks. Illicit actors that operate in hostile environments characterized by state agencies trying to destroy them are likely to benefit from densely-linked clusters and redundant bridge nodes. Small, tightly-connected clusters allow individuals to coordinate their activities while minimizing their exposure to external actors who seek to destroy them. Multiple bridges increase network unity by allowing information and other resources to jump from cluster to cluster through redundant shortcuts. While these structural properties may not be optimally suited to all underground networks, they have provided some illicit actors such as al-Muhajiroun a measure of resilience they lacked when assuming more centralized, scale-free forms. Al-Qaeda experienced a similar metamorphosis in the war on terror when its original, relatively centralized structure (“al Qaeda Central”) transformed into a more diffuse global movement characterized by largely autonomous local clusters linked through shared goals and a common ideology (the “al Qaeda Movement”). ISIS, which already relies on clusters of supporters to recruit fighters from Western Europe and the United States, may eventually experience a similar transformation as Coalition forces and their allies in Iraq and Syria bring their superior resources more effectively to bear on the fledging Islamic State. As the long war continues in the months and years ahead, scholars and practitioners would do well to remember the lessons of al-Muhajiroun’s solution by focusing on the connectivity and cohesion often found in small-world networks.

Michael Kenney is an Associate Professor of International Affairs at the Graduate School of Public and International Affairs at the University of Pittsburgh.

2 comments

“radicalised”, “violent extremism” blah blah

all he is is an Islamic scholar who has taught others orthodox Islam and expressed his opinions

the solution to choudary and his pals is simple, pack them off to Syria

they can get blown up in American airstrikes, whoopie