By Erica Chenoweth for Denver Dialogues.

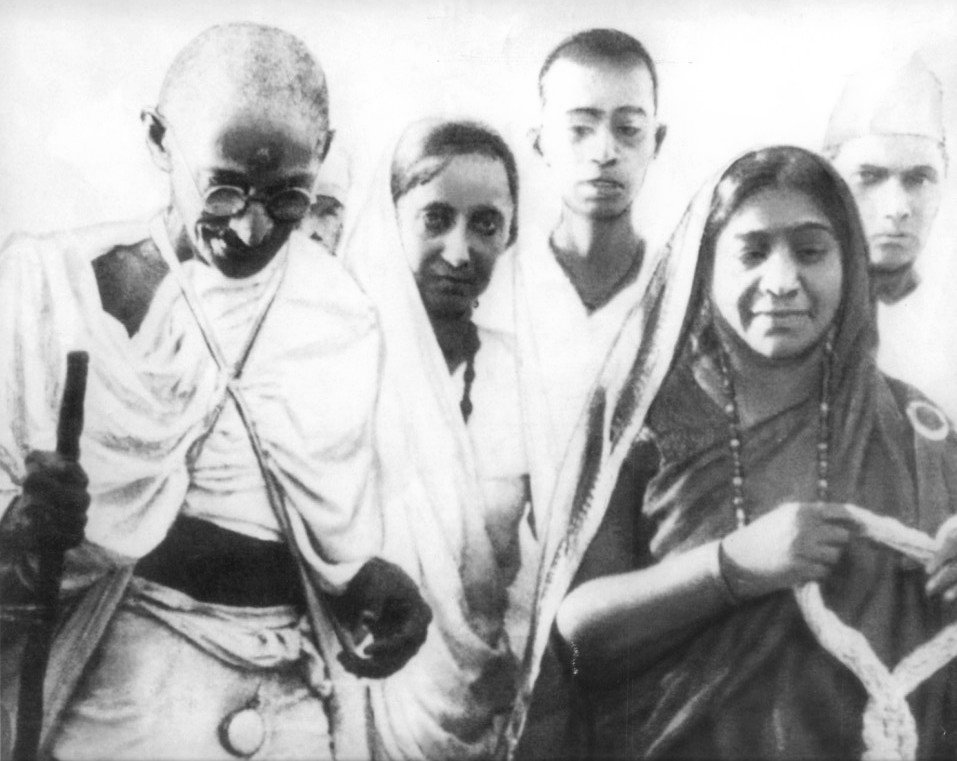

Today is Gandhi’s birthday, which the United Nations now annually celebrates as the “International Day of Non-Violence.” Early this morning, the UN Tweeted one of the better-known quotes from Gandhi’s autobiography:

“There are many causes that I am prepared to die for but no causes that I am prepared to kill for.”

In this simple expression, Gandhi captures one of the main advantages of nonviolent resistance when it comes to mass mobilization – that, like himself, most people are willing to become victims or martyrs rather than to become perpetrators of offensive violence. Indeed, moral clarity about victim and perpetrator can be a powerful framing mechanism in the context of mass movements – both in terms of motivating individual participation and in terms of the ability to win legitimacy for a movement as a whole.

With regard to individual participation, Wendy Pearlman shows the enduring power of “moral identity” in creating protest cascades during the early days of the Syrian uprisings, despite (and/or because of) escalating brutality against nonviolent protestors by the Assad regime. She finds that early risers in the Syrian uprising conjured moral ideals to motivate people to participate as a matter of self-respect and personal agency. She also finds that the willingness to sacrifice oneself activated the sense of obligation among other Syrians to continue the struggle. This case echoes insights from previous studies of social movement building and effectiveness. In identifying successful movements, for example, Charles Tilly identified the acronym “WUNC”—short for collective worthiness, unity, numbers, and commitment—as essential elements.

Recent studies tell us a bit more about when early risers are able to make these compelling or “worthy” moral appeals, and their willingness to rely on nonviolent methods is key. Indeed, the lower moral barrier to nonviolent resistance is a key reason why nonviolent movements tend to have a higher rate of mass participation than violent ones. When movements remain nonviolent more generally, observers are better able to arrive at moral clarity about injustice.

Gandhi learned this consistent pattern from his own “experiments” while organizing, mobilizing, and planning for mass civil disobedience in South Africa and India. Indeed, it was Gandhi who coined the term “civil resistance”—a concept used widely today. Others who emulated and extended his methods—in the United States, South Africa, and beyond—have likewise recognized the power of dramatizing injustice in a way that provokes a moral crisis within the polity.

Recent scholarship also confirms this pattern through surveys (see here and here, for example) and quasi-experimental research. When people observe dissent and repression, they tend to empathize with nonviolent resistance at much higher rates than violent resistance taking place in identical circumstances. And this empathy among observers often translates into changes in attitudes and beliefs about minority groups, public opinion about rights to protest and freedom of expression, legislators’ behavior, election outcomes, and direct participation in nonviolent resistance. These changes, in turn, can have profound long-term benefits for economic well-being, equality, justice, and democratic institution-building.

Of course, moral crises (and the nonviolent actions that often provoke them) are not always enough to produce mass mobilization or meaningful change for aggrieved populations, especially in deeply-divided societies. Systems of power and oppression, like white supremacy and racism, patriarchy, and imperialism, are remarkably enduring structures that also seek to justify their persistence on the basis of moral claims, however unjustifiable those claims may seem to all but the privileged few. For instance, Omar Wasow finds that respondent race affected baseline attitudes regarding whether civil rights was a superior moral claim to “law and order” during the U.S. civil rights movement. Similarly, a recent study by Christian Davenport, Rose McDermott, and David Armstrong shows that racial difference between protestors and police can lead respondents who are racially similar to police to question whether protest is morally justified. (Several of the excellent articles in a recent issue of the Journal of Global Security Studies further display these patterns.)

It is no accident that many perpetrators of violence and beneficiaries of oppressive systems take such great pains to describe themselves as victims, and why they tend to characterize violence as self-defense from grave threat. It’s because they know the power of the moral argument.

Gandhi recognized that these political realities placed an unfair burden on oppressed populations to maintain the moral high ground in the face of excessive brutality. And although achieving the moral high ground does not guarantee success, the ability to win the battle for legitimacy by making more compelling moral appeals nevertheless appears to be a necessary process in achieving meaningful change and overcoming systems of oppression. Ultimately, success occurs not by converting or persuading the oppressors, but by dividing their allies and building new systems from below. Such arguments speak to the necessity of expanding participation in movements to include a cross-cutting base of supporters, which creates divisions within the oppressive system or group. And, as this expanding body of literature shows, a commitment to nonviolent methods often make it easier for this cross-cutting base of supporters—and potential defectors—to join the struggle.

Much of the current literature about nonviolent resistance remains deliberately detached from the moral dimensions of the technique, opting instead to focus on strategies of civil resistance. But it is always worth recalling the simple yet powerful fact that the basic foundation of the strategy of civil resistance is usually a moral one. On the day inspired by the man who gave civil resistance its name, this remains a crucial lesson for scholars and practitioners of resistance alike.

— This post was updated from the original at 5pm EST to reflect some revisions and further detail. —