Guest post by Pearce Edwards and Patrick Pierson.

In Venezuela, the rule of President Nicolás Maduro appears increasingly fragile. Dozens of nations have recognized opposition leader Juan Guaidó as the country’s legitimate president, and protesters took to the streets by the tens of thousands in recent weeks to protest Maduro’s claim to power. Despite the unrest, Maduro is more resilient than he appears. Here’s why.

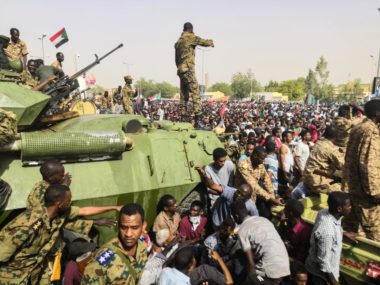

Research shows that authoritarian rulers confront two potential threats to their rule—those emanating from other elites and those that emerge from the masses. Coverage of the unrest in Venezuela has paid close attention to the first of these, especially the military’s ongoing support for Maduro. But what about the second?

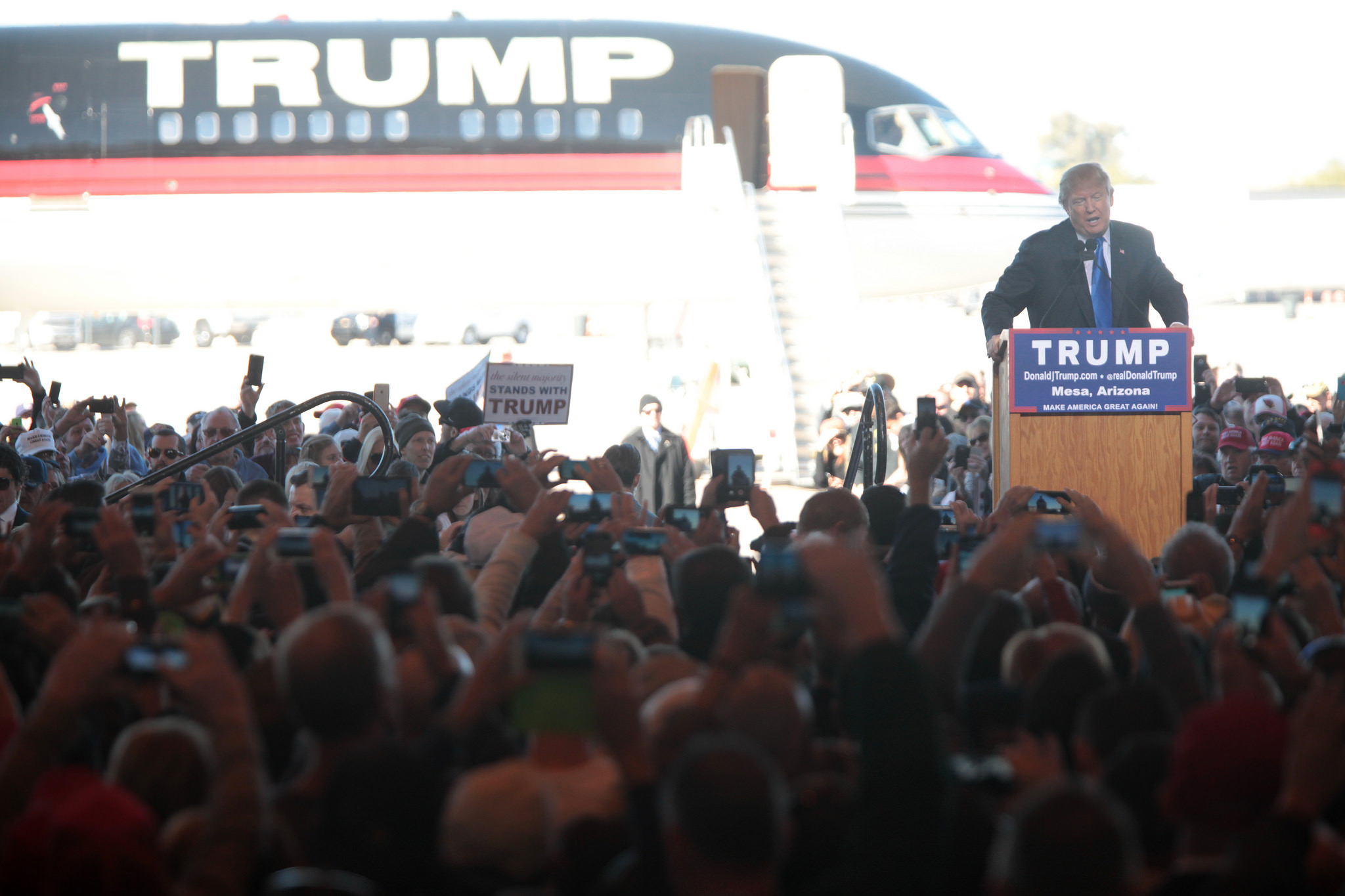

Lacking sway over the military, opposition leaders are encouraging mass protests and street demonstrations in an effort to force the government to the negotiating table. How will Maduro respond? So far, the government has refrained from large-scale, indiscriminate repression of protesters, a response that can incite anti-regime backlash among citizens and may provide a pretext for foreign powers to intervene in domestic politics—something the Trump administration has not ruled out.

But violence is not the only tool dictators use to counter mass threats. As our research shows, government’s rely on carrots—as well as sticks—to stabilize their rule.

Service Provision and Authoritarian Control

More than a decade ago, the Venezuelan government started working with ZTE, the telecom company responsible for China’s vast network of government surveillance. In 2017, Venezuela rolled out the Carnet de la Patria (Fatherland Card), a move to ostensibly streamline the provision of state-administered welfare, including goods such as pensions, housing bonds, healthcare, and food subsidies.

According to state officials, more than 18 million Venezuelans, or 55 percent of the population, have registered for the card over the last two years. The government then launched a brigade of pro-regime loyalists to help verify citizens’ information in the Fatherland system in an effort to “optimize the scope and advancement” of the country’s social programs. Nearly 400,000 Maduro loyalists have joined the brigades, visiting 3.5 million communities in the past two years.

And while the carnet may indeed expand the scope of the country’s myriad social welfare programs, it also allows the government to gather extensive personal data on citizens, including family information, financial assets, state benefits received, voting history, and social media presence. Our research notes that dictators use this counterintuitive tool—the provision of social services such as education and healthcare—to gather information about potential dissidents and make repression more targeted and efficient. We find that dictators are more likely to use social services as a tool for information-gathering when a society is highly divided between supporters and opponents of the dictator. We also find dictators are more likely to use social services for repression when economic conditions are poor.

In Venezuela, a country politically divided and economically desperate, the government uses social services to overcome one of the primary challenges confronting autocratic leaders in the face of mass unrest—namely, a lack of information about potential dissidents among the populace. This may help to explain the Maduro regime’s willingness to allow mass protests during the current unrest. Compare this to anti-government protests in 2016, when Maduro responded with a heavy-handed crackdown against protesters. So far, the response to the current crisis has been much less overt, with Maduro turning to a recently-created secret police to discreetly carry out his dirty work. With more information about citizens, the government can avoid indiscriminate mass repression and instead use targeted violence to strategically eliminate leading dissidents.

In addition to the troves of information the carnet system provides, the country’s economic collapse has made the card even more invaluable. In 2018, Venezuela’s annual inflation rate hit 80,000 percent—a dozen eggs now costs the equivalent of two weeks’ pay at minimum wage. Under these dire circumstances, mere survival is a daily chore for many. Recognizing this, the government has increasingly relied on the card to manipulate citizens’ access to subsidies on basic goods such as gasoline and flour. While the Maduro regime may not be very popular, it is now the only lifeline for many of the country’s most vulnerable.

What does this mean for Venezuela?

At this point, the near-term future in Venezuela is anyone’s guess. What our research does show, however, is that the regime’s grip on power is sustained by much more than military might and the allegiance of key elites. In Venezuela, even social goods are used for political repression and social control. The political challenge to Maduro isn’t going away, but he might not be either.

Pearce Edwards is a PhD student in the Department of Political Science at Emory University. You can follow him on Twitter @pearceaedwards. Patrick Pierson is a PhD student in the Department of Political Science at Emory University. You can follow him on Twitter @plpierson.