Guest post by Lisa Langdon Koch and Matthew Wells.

Seventy-four years ago last week, the United States dropped the first atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Would Americans support the use of nuclear weapons again?

Despite the possibility of talks between President Trump and North Korean leader Kim Jong Un, a shocking percentage of Americans—one-third—say they would support a nuclear strike against North Korea, according to a study published last month in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists.

Nuclear weapons are incredibly devastating. The blast, radiation, and firestorm from a nuclear explosion would cause unspeakable human suffering and environmental damage. Why, then, are so many Americans willing to inflict such harm on North Korean civilians? We have reason to believe that many may be both unaware and misinformed about the horror of a nuclear strike.

Last year we conducted a study with the polling firm YouGov, and results shows that learning about the real-life consequences of nuclear weapons can make a difference in Americans’ attitudes about using them against foreign civilians. We presented our survey respondents with a choice: they could use either nuclear weapons or conventional bombs to strike an enemy foreign country that was trying to develop nuclear weapons that could someday pose a threat to the United States.

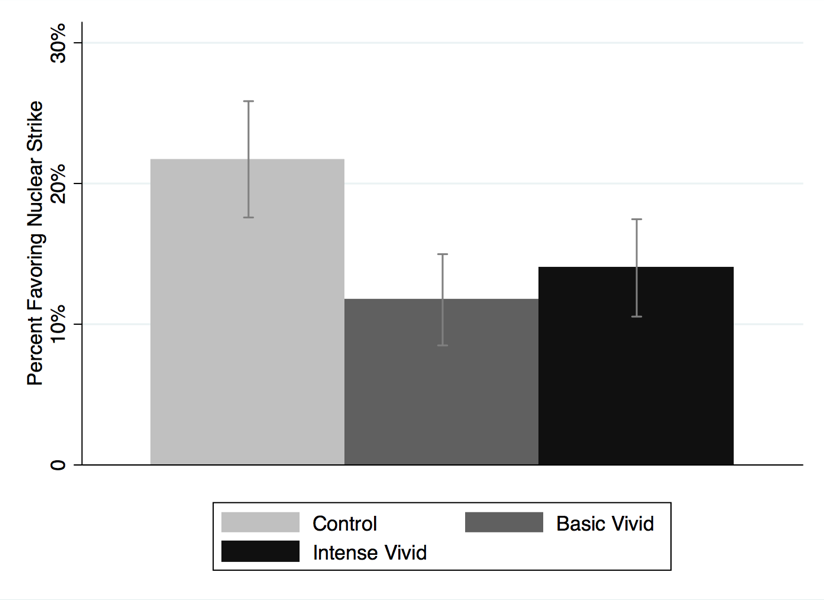

Twenty-two percent of respondents chose the nuclear strike when we simply asked them to choose but didn’t give them information about the aftermath (control condition in Figures 1 and 2). Many of these respondents reported that they believed a nuclear attack had a better chance of succeeding. But there were other reasons, too. One respondent said: “I chose the nuclear option because I would rather people not suffer than to linger on from a cruise missile attack.”

Here’s why this is important. The idea that nuclear weapons will quickly, even painlessly, kill people is a common misconception. In reality, survivors endure terrible burns and other severe and painful injuries—and the effects of radiation continue to do harm to the body long after the war is over.

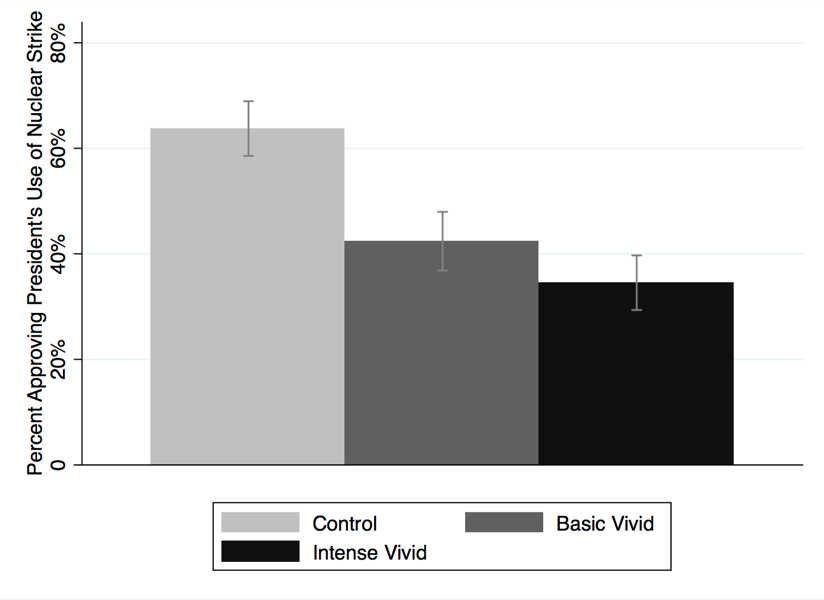

To account for this reality, we also varied the information survey respondents received about the effects of nuclear weapons, as well as those of conventional weapons. Some respondents learned about what would happen to the buildings and surrounding environment in the attacked city (“basic vivid” condition in Figures 1 and 2). Others learned about what would happen to civilians (“intense vivid” condition in Figures 1 and 2).

When we provided real-life information about the suffering and damage that nuclear and conventional strikes would cause, Americans were significantly less likely to support the use of nuclear weapons. The survey respondents who learned about the human suffering caused by nuclear weapons also had higher levels of sympathy for potential civilian victims.

Exactly how much of a difference did this make? Learning about the consequences of a nuclear attack next to those of conventional weapons resulted in a much lower level of approval for a US nuclear strike:

- Fourteen percent of those told of the effect on civilians approved of a US nuclear strike, down from twenty-two percent approval of those without such information;

- Perhaps even more striking, sixty-seven percent of Americans who didn’t learn about the consequences said they would approve of a president’s decision to conduct a nuclear strike.

- But only thirty-five percent of Americans who learned about the harm to foreign civilians said they would approve.

Figure 1. Responses to the question: “If you had to choose between one of the two US military options described in the article, would you prefer the nuclear strike or the conventional strike to destroy the nuclear weapons facility?”

Figure 2. Responses to the question, “Regardless of your decision, would you approve of the president’s decision if he chose to conduct a nuclear strike to destroy the nuclear weapons facility?”

In the months after the United States dropped atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, word began to spread that the residents of those cities had suffered unique horrors. Fearing that public outrage would make nuclear weapons unusable in the future, government officials who supported their development—like General Leslie Groves—worked hard to downplay their singularly devastating effects. That November, Groves even insisted to a Senate committee that radiation exposure was a pleasant way to die.

Our study indicates that Groves was right to worry about how much Americans knew. People’s beliefs about the damage wrought by nuclear weapons matter. If we are to prevent the use of nuclear weapons, it is vital to teach people about the terrible harm they cause. Americans will oppose inflicting horrific suffering on others, even in war—but too few may know that nuclear weapons will cause such harm.

Lisa Langdon Koch is Assistant Professor of Government at Claremont McKenna College. Matthew Wells is Assistant Professor of Political Science at Wabash College. This research was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the authors.

1 comment

And this is why most working class Americans are right to abhor their academe betters.

Dr. David Jacobson