The Obama Administration continues to insist that it would like to see a diplomatic solution to the civil war in Syria. But this desire flies in the face of everything we’ve learned about how civil wars have ended over the last 70+ years. Here are four things that President Obama should keep in mind as he considers the feasibility of pushing for a negotiated settlement in Syria.

- Civil wars don’t end quickly. The average length of civil wars since 1945 have been about 10 years. This suggests that the civil war in Syria is in its early stages, and not in the later stages that tend to encourage combatants to negotiate a settlement.

- The greater the number of factions, the longer a civil war tends to last. Syria’s civil war is being fought between the Assad government and at least 13 major rebel groups whose alliances are relatively fluid. This suggests that Syria’s civil war is likely to last longer than the average civil war.

- Most civil wars end in decisive military victories, not negotiated settlements. Of these wars governments have won about 40% of the time, rebels about 35% of the time. The remainder tend to end in negotiated settlements. This suggests that the civil war in Syria will not end in a negotiated settlement but will rather end on the battlefield.

- Finally, the civil wars that end in successfully negotiated settlements tend to have two things in common. First, they tend to divide political power amongst the combatants based on their position on the battlefield. This means that any negotiated settlement in Syria will need to include both the Assad regime and the Islamists, neither of whom is particularly interested in working with the other. Second, successful settlements all enjoy the help of a third party willing to ensure the safety of combatants as they demobilize. This means that even if all sides eventually agree to negotiate (i.e., due to a military stalemate or increasingly heavy costs), it’s unlikely that any country or the U.N. will be willing to send the peacekeepers necessary to help implement the peace. The likelihood of a successful negotiated settlement in Syria? Probably close to zero.

48 comments

I wonder if there is an average difference in length or intensity of civil wars backed by external parties, as the Syrian war is reported to be, versus those which are not. It seems to me the former variety could go on for a very long time since military success or failure would not affect viability of the combatants. I’m thinking of the Contra war in Nicaragua as one example; Angola would be another. Externally-backed wars would also usually require different kinds of resolution involving the intervening powers and, most likely, very different issues than those motivating the in-country combatants.

Research suggests that wars with third-party interventions (including external support) last longer, on average, than wars in which there are no external backers for either side. However, when the international community picks one side–where there is uniform backing only for the rebels or the incumbent government)–civil wars tend to be shorter than when different international players back different parties (as in Syria). See: http://jcr.sagepub.com/content/46/1/55.refs.

Thanks for this. PVG is doing an excellent job in connecting quantitative conflict literature to current-day issues on a regular basis! Extremely useful.

On quick thought, though: #3 is a bit misleading, at least to me, but correct me if I am wrong: Syria is likely to end on the battlefield not because a majority of all the other civil wars that have been fought also ended on the battlefield, as the post suggests. Rather, Syria is likely to fail to reach a negotiated settlement as a consequence of the underlying factors that push it towards an end on the battlefield; factors Syria shares with the other cases that didn’t end in a settlement either. In terms of your theory, this underlying factor would be (the lack of) external security guarantees for the belligerents to enforce an agreement, (lack of) a military stalemate, costs. This becomes a bit more clear in #4, but #3 sounds a bit off. It’s not the fact that most civil wars have ended in victories, but rather the factors Syria has in common with these cases that suggest that Syria is unlikely to end in a negotiated settlement. Or am I missing anything?

If a war is largely driven by external parties, as the war in Syria appears to be, then it is unlikely to end before the external parties lose interest in it. That may have little to do with conditions inside the country. Both (or all) sides have in effect great strategic depth. However, the fact the the U.S. president could not obtain Congressional backing for a more explicit venture into Syria suggests that the U.S. may be losing interest, which can be expected to affect the policies of its allies or satellites in the region.

With Saudi Arabia’s recent decision to spurn the Security Council position (to the apparent shock of even its diplomats) I don’t think Saudi Arabia is going to forget it any time soon.

The Saudi move is as yet obscure. It may be the surface manifestation of some kind of falling-out among the U.S. ruling class, with some parties electing to go private in response to the failure of the Administration to get behind the recently-proposed overt military intervention. That sort of thing has been observed before. There are important Americans with close ties to the Saudi regime.

There is a fundamental flaw in this analysis: the conflict in Syria has never been a “civil-war.”

One armed belligerent is a domestic actor with popular support. The other armed belligerent is a foreign funded, foreign-dominated entity with a foreign ideology & foreign political aims – portrayed in the west as having popular domestic support and duplicitously conflated with a legitimate protest movement calling for reform. This latter militant entity holds hardly any support within the Syrian population, and what support it did have has decreased rapidly as the true nature & ideologies of it have been exposed.

Without years of policy planning & fomentation (thank the Saudis for the foreign Wahhabi ideology) massive foreign funding, thousands of foreign militants, arms, logistical and political assistance there would be no armed “opposition”, ergo: no “civil” war.

The conflict in Syria is a foreign-funded, and foreign instigated sectarian insurgency with the aim of destroying a state that refuses to bow to western/GCC demands & has acted as the “keystone” to regional resistance to western/Saudi/Israeli hegemony: not a civil war. The “rebels” are not only alien to the masses of Syrians that support their government and army, they are also alien to the majority of Syrians that dont support the Assad regime.

When the “International Community” stop funding, facilitating, and turning a blind eye to their regional partners’ efforts to excacerbate and prolong the military conflict, the war will dissipate. But until Saudi & other key sponsors of militant Wahhabi/Salafism are brought to account & stopped, Syria will resemble the other targets of Saudi aggression – the Iraq scenario (a low-level insurgency, again, reliant on foreign funding) is the most likely short-to-medium term outcome in Syria.

Thank for you this reply. I have been studying the conflict in Syria quite intensely lately, all the facts where pointing me somewhere- you just summed them up.

If this was as you describe then I don’t believe we would have seen it last as long as it has across so much of the nation with reports of some Syrian refugees returning to fight against the Assad government. I’m sorry but I can’t use that description any more than I could George W. Bush’s description of the violence in Iraq being caused by foreign Sunni terrorists.

If one side of a war is resourced externally by a large foreign power, it can last indefinitely. A good example is that of the Contras in Nicaragua, who, because they were backed by the U.S. (or parties within the U.S.), were able to keep going for nearly ten years even though they never managed to move much beyond terrorism and never held any territory. This did not mean they were all mercenaries; some of the Contras were no doubt motivated by ideology.

It isn’t easy for even the U.S. to just move the money that would be needed for something on the level of the Contra funding (and remember that details about that leaked by the 1980s) and if the U.S. was funding and supplying any of the Syrian groups to that extent I’d expect to hear about major battlefield successes and the rebels on the road to Damascus again.

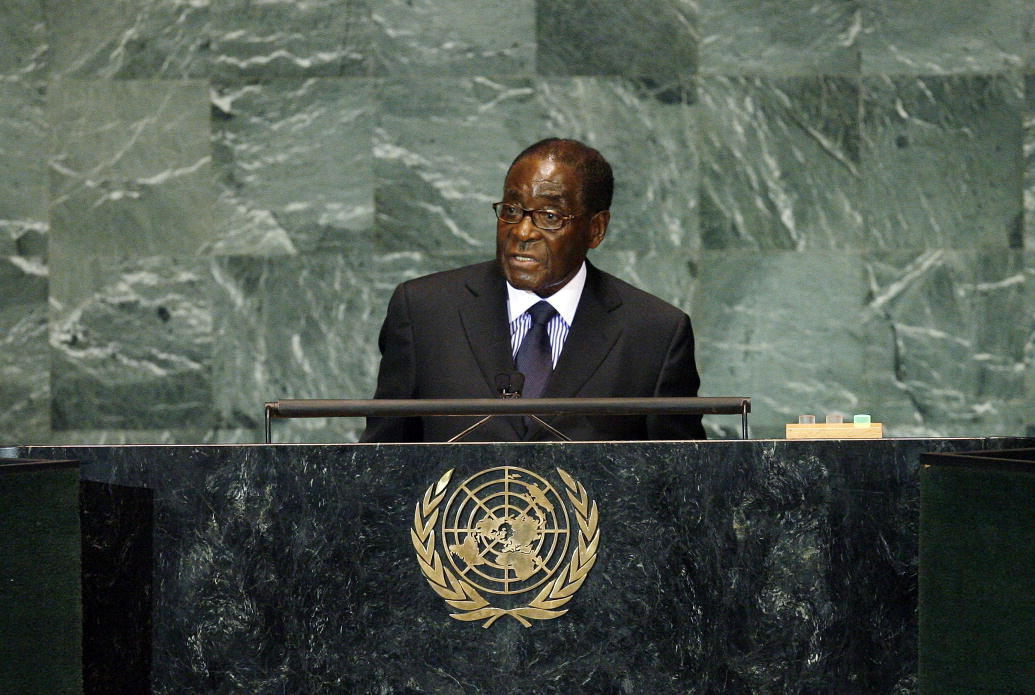

you should get permission and pay a usage fee to the photographer, Narcisco Contreras. His agency is Polaris Images, 212-967-5656

Thank you for your notice. I was unaware that the image was copyrighted, as the source linked through to did not credit the photographer. I have taken down the image.

Thank you again.

-Taylor Marvin

what about Libya? No fly zone = quick end to Qadaffi regime. I know the rebels weren’t divided but neither were the Syrians 2 years ago.

I believe considerably more was done in Libya than the establishment of a no-fly zone.

In Libya NATO (mostly American) planes caused severe damage to Qaddafi’s forces, far more than I personally I would have expected on their own. A no-fly zone is typically understood to be focused around preventing the use of aircraft around a location.

What about the Kurdish element in this equation? All your posts have failed to consider the Kurdish population’s role in the Syrian crisis. By doing so, your analysis is missing a lot and you’re misleading your readers by presenting a the crisis as a battle between Assad v. ’13 rebel groups.’ If you follow the crisis closely, you will see that the Kurds fall neither on the side of Assad nor in the rebel camp.

I’m not sure where you are getting your information, but good topic.

I needs to spend some time learning more or understanding more.

Thanks for excellent information I was looking for this information for my mission.

Reblogged this on مدونة مؤنس.

your article doesn’t say what is the odds the rebels will succeed if they were the large majority fighting a small minority like in Syria. Any studies about that? Thank you

Who would think a black man would become president of the USA. That didn’t accur the last 200 years either.