Guest post by Brian J. Phillips

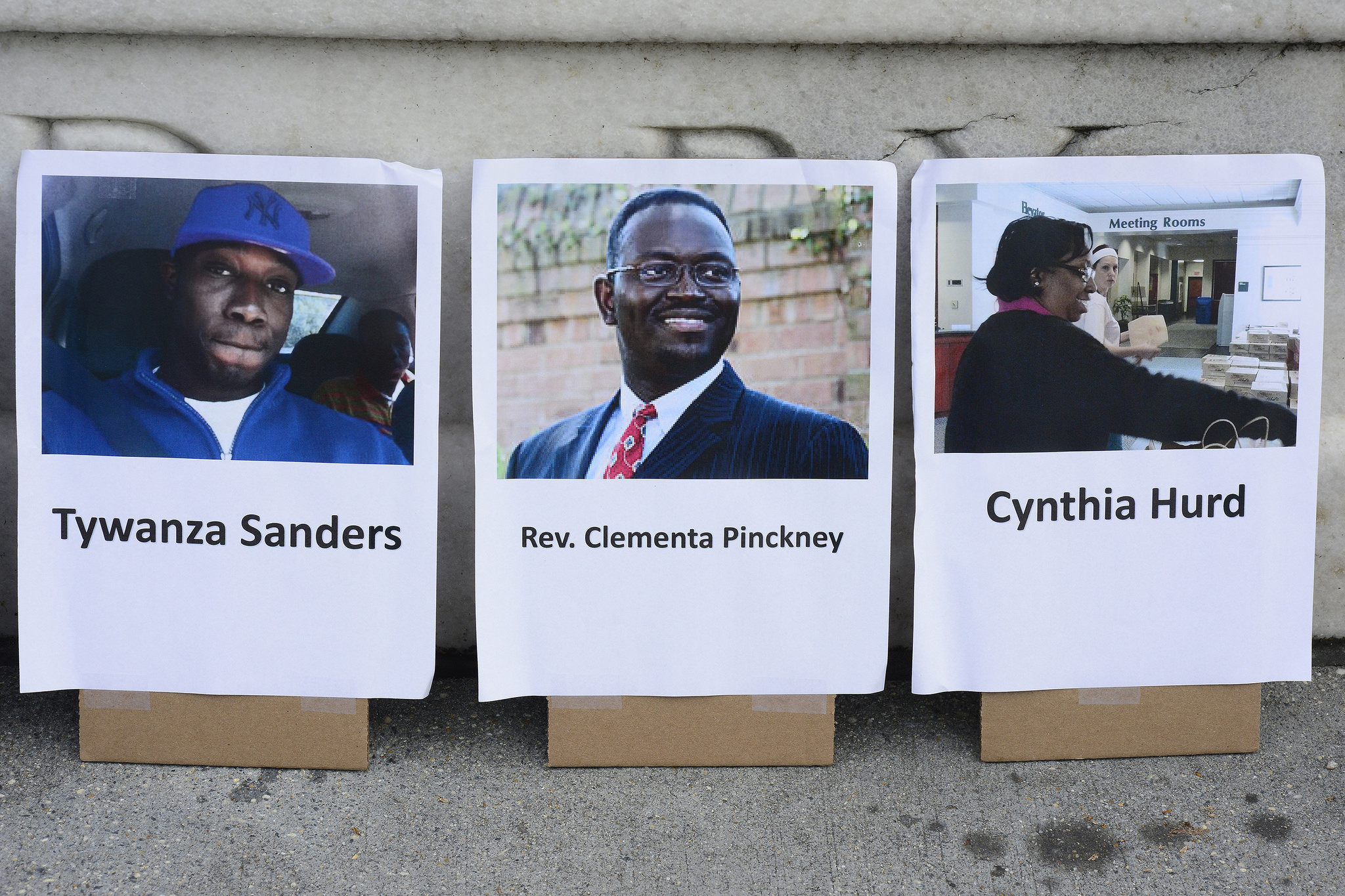

The accused shooter in the Charleston massacre apparently wrote a manifesto, which can be found online various places. Two things jumped out at me when I first read it: First, the shooter was clearly motivated by racism. Some politicians or pundits said we can never understand what motivated the Charleston shooter, but the manifesto is entirely about his racist motivation.

Second, the text contains many elements that are familiar to readers of the academic literature on terrorism, and to those of us who have read other terrorists’ writings. The manifesto adds evidence to the argument that this attack was textbook terrorism.

A note: one is hesitant to discuss the manifesto, as it gives more attention to a hate-filled monster. However, as students of conflict it is helpful to understand why individuals carry out their violence, and we do not always get such detailed and direct explanations.

A manifesto: Classic terror behavior

Terrorism was described as “violence as communication” more than 30 years ago, and “propaganda by the deed” (or “of the deed”) more than 100 years ago. Terrorists have generally sought to send out a message, whether claiming attacks with calls to newspapers, or producing videos for diffusion on the Internet. Sending a message is one of the key elements that separate terrorism from other types of violence.

In 1996 the FBI caught the Unabomber – who carried out more than a dozen attacks, killing three people – because the writing style of his recently-published manifesto was recognized by his brother. The Unabomber’s need to communicate his political views, in the end, was what sent him to prison.

Like the Charleston’ shooter’s manifesto, the publication of an explanation on the Internet before attacking was exactly what Anders Breivik did in Norway in 2011. He wanted the world to know why he had killed 77 people. Or, he killed 77 people to get the world to read his political views.

Beyond manifestos, the need to communicate why one is engaging in violence is common among those who use terrorism. Suicide terrorists produce “martyr videos” before their final act, and terrorists have written their own autobiographies, which have been quite helpful to researchers.

Terrorism as a weapon of the weak

It’s an age-old idea that terrorism is tool for those too weak to engage in warfare such as attacking combatants. The shooter seems to suggest that idea in his manifesto, writing, “I am not in the position to, alone, go into the ghetto and fight.” He thought a massacre was his only option to make a statement with violence.

Lone wolves instead of terrorist groups

The author laments that “We have no skinheads, no real KKK.” This is basically an explanation for why he is acting alone. Why is there “no real KKK”? One factor is that U.S. law enforcement and counterterrorism efforts since the 1990s, such as infiltrators and intercepted communications, have made operations difficult for hate groups and other terrorist organizations.

Even in the 1990s, prominent figures in the right-wing movement encouraged followers to act on their own. Organized violence was too risky in a country with advanced counterterrorism capacity. All it takes is one tip to the police to bring down an operation. (This was how a planned attack against black children and President Obama was disrupted in 2008, as Will Moore recently reminded us online.) Jihadist groups have told acolytes in the West in general the same – act on your own.

For a clear history of how lone wolves emerged in the U.S. and other developed countries in part because of counterterrorism pressure on groups, see the beginning of Paul Gill’s book. On the lethality of lone wolves compared to that of terrorist groups, see here.

Even lone wolves have friends

A popular topic in violence research is “radicalization.” Why do individuals start to engage in terrorism? For reasons discussed above, as the lone wolf phenomenon becomes more common in some countries, would-be terrorists increasingly learn about radical ideologies and violent tactics online.

The Charleston shooter apparently acted alone, but his manifesto makes clear that he learned from others online. He describes searching the Internet for information about “black on white crime,” and being captivated by the site of one group in particular, the Council of Conservative Citizens. The Southern Poverty Law Center describes the group as racist. Interestingly, the group has donated to the campaigns of three men currently running for president.

He also expresses disappointment that other white supremacists were only interested in “talking on the Internet.” Did he try to get others involved in his plot?

Beyond the Internet, he apparently told friends that he wanted to start a race war. Others heard about his plans, and did not report them to the authorities. Additionally, who took the now-famous photos of him – including of him aiming a gun? Overall, even lone wolves have a support network to some degree. Interrupting a lone-actor is much more difficult than stopping a terrorist group, but there are steps that other citizens and law enforcement can take.

Ready to die

Finally, he ends his manifesto as some others have, suggesting he does not expect to survive his rampage. He writes that some of his “best thoughts” have been left out, and therefore will be “lost forever.”

When a college dropout in California uploaded a misogynist and racist manifesto just before starting a “war on women” killing spree in 2014, he wrote, “this is how my tragic life ends.” And he did indeed kill himself after killing six others.

The suspected Charleston shooter, however, was arrested without incident, and now awaits a trial. We might hear more of his “best thoughts” yet. But he apparently posted the manifesto just in case he didn’t get the chance to share his propaganda. It was that important to him that we know about his white supremacist views. Violence alone was insufficient. And whether he lived or died, he wanted to spread terror.

Brian J. Phillips is a professor at the Center for Research and Teaching in Economics (CIDE) in Mexico City. His research focuses on the causes and consequences of sub-national political violence.

2 comments