Guest Post by Reed M. Wood

The worsening Syrian insurgency pressures the US and its allies to respond. Two commonly debated options include harsher sanctions and military intervention. Neither approach is ideal as both risk doing more harm than good, at least in the short-term. But let’s face it: policy makers are often faced with choosing the best of bad options. To that end, the best (but by no means easiest) option available is impartial multilateral intervention.

Let me first deal with sanctions. Sanctions are often popular at home and help well-intentioned leaders feel that they are doing something “good.” However, they have a mixed record of success, particularly against autocrats. Worse, sanctions often lead to more rather than less repression and abuse. Targeted sanctions might mitigate collateral damage, but there is little evidence of their success in deterring serious abuse.

Military intervention has the best chance of ameliorating human costs. The tricky issue is designing the right intervention strategy. Not all interventions are equal, and the wrong intervention could prove more costly than inaction. Most foreign interventions initially provoke a surge of violence—something the international community should prepare for. Yet, over the longer-term impartial interventions appear better able to mitigate mass violence compared to those that explicitly support the opposition.

The biggest question is how to construct and implement a “neutral” intervention, especially given that Russia is almost certain to block UN peacekeeping. By no means should the US abandon the pursuit of UN peacekeeping—there’s always the hope that Russia abstains, right? Yet, until that unlikely scenario occurs the US, its allies, and other states concerned with humanitarian law and global stability should work toward building a peacekeeping coalition capable of both protecting civilians and establishing the conditions that allow both sides to commit to peace.

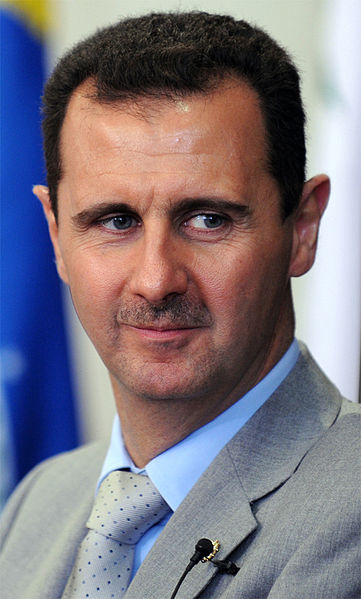

Constructing such a coalition, especially if done on an ad hoc basis, poses a number challenges (legality, perceptions of impartiality, disagreements over troop commitment, etc.). Yet available alternatives look worse. Biased intervention will almost certainly contribute to more violence. True, Western powers could oust the regime, but human costs will rise rapidly until that occurs and probably after as well. It would be dangerous to presume a repeat of Libya will play out in Syria. Gadhafi could muster fewer than 100,000 troops, including mercenaries; estimates of Assad’s forces are closer to half a million. Even a forceful intervention is therefore likely to take time, creating a large window in which the regime will fill thousands more graves. Moreover, existing communal tensions suggest the potential for spiraling violence in the wake of regime collapse. While close parallels to Iraq should be made with caution, recent history is nonetheless instructive.

The point is, direct challenges to the regime might sound appealing, but the political reality is far messier. Any intervention strategy should anticipate and prepare for unintended surges in violence. Moreover, they should include a clear plan for resolving the underlying political conflict. Unbiased interventions stand the best chance of the latter and are no more detrimental to the former.