It used to be that the United States liked to take its enemies alive — at least most of the time, or at least so it seemed. After WWII, the US did not hand over any of Hitler’s inner circle to the Russians and certain death. Had the Western Allies been able to capture Hitler, he would have stood trial at Nurenberg and not been delivered to a mob. Over the last five years, however, this commitment to capturing enemy leaders alive appears to have changed. The US deposed Saddam Hussein and then handed him over to the new interim govenrment of Iraq — which was dominated by Hussein’s sectarian enemies — knowing that they would almost certainly kill him. The same could be said about Gaddafi, who was toppled as a result of NATO assistance to the rebels in Libya. The day Gaddafi was killed he was the target of French airstrikes that then allowed Libyan rebels to capture him, before brutaly and publicly killing him. Osama bin Laden’s death was even more direct. The United States sent in a team of SEALs with orders to kill on sight.

It could be that the United States had no control over the final fate of Saddam Hussein or Muammar Gaddafi, and that there really isn’t a pattern to how the US has been removing its enemies. But the fact that three of our worst adversaries have all died in the last few years either at our hands or in the hands of our allies suggests that we are sanctioning this behavior. So the puzzle I’m posing today is: why does the US suddenly want its enemies dead, not alive?

Best Answer to Our Last Puzzler:

Two weeks ago I posed the question of why CVS would still sell Walkmans when the technology has been obsolete for over twenty years. There were lots of interesting theories about who might use this antiquated technology — hipsters, old-schoolers, deployed service members, alien fear-mongers — and why they might use them. But the best and most plausible answer came form Pauline, Taylor Marvin and Squarelyrooted.

It’s true: I live in a wealthy community north of San Diego. The median income is above the national average, and certainly high enough for most families to afford a personal computer. But wealthy families in the community are serviced by a large group of immigrant Mexican families who also live in the area — often within walking distance of shopping areas. These families may not have the money to afford a personal computer. They are also less likely to use the public libraries that offer free access to computers. This means that if this subset of the population wants to listen to mobile music, the ONLY option they have is to buy a Walkman or a Discman. What this experience brought home to me was the huge and growing gap between those who have the money to access technology and those who don’t. If you can’t afford a personal computer, you can’t access all the information and knowledge the web has to offer. You also can’t even move beyond the Walkman. Having no access to a PC leaves you behind in every dimension.

12 comments

It’s because our alternatives have been narrowed. It is impossible to imprison these people under our jurisdiction because of the lawfare waged by all of the self-appointed human rights groups. It’s just too much of a headache and disruption. The legal entanglements today are enormous. We still haven’t started KSM’s trial nine years after his capture. It’s why the Obama administration stepped up the pace of drone attacks. We can’t capture these folks anymore, it’s simpler to kill them even though there may be significant intelligence value in capturing them. It is for this reason that I predict that American military actions in the future will be much shorter and much more violent and employ disproportionate force. The longer you stick around in these situations the more likely it is you’ll be emeshed in the human rights legal quaqmire.

For the Nuremberg trials we were able to detain defendants indefinitely, use testimony extracted under threat, have hearsay and other evidentiary rules that were much looser than those under today military tribunals, and have the rulings of the trial judges unreviewable by any other court. You can’t do that today.

I echo Marks’ comments that the preference for killing is derived from issues with the legal system. I differ, however, in how the legal system presents barriers to its use by US leaders and argue that the barrier has more to do with public scrutiny than with laws of evidence.

The reason for pursuing the “better off dead” option is in part due to the more stringent evidentiary guidelines (in contrast to the Rules of Engagement for pulling the trigger) and a reduced certainty about obtaining a conviction. More importantly, though, the legal option represents a public check on the decision making of the executive branch – from the President to the Soldier. Trials threaten to allow the light of day to reach the process of identifying and punishing enemies of the state, and subject this process and these officials to public review.

A final piece of the preference for military based killing is audience costs. It is less costly (nationally and internationally) to execute someone via a military strike than it is to put that same person to death via the legal system’s normal means of prisoner execution. Imagine the churn of a lengthy trial and then state execution of Bin Laden.

Drone strikes and covert operations are preferred because they provide a means to deny transparency.

I think it’s because our system of imprisonment became a driver of insurgent recruitment. I think the detainee mistreatment scandals, not to mention the outright instances off torture by waterboarding and the like,are at least on par if not possibly more inflammatory than the deaths in a similar situation. Digital pictures of course are a multiplier there.

The U.S. Congress’s denying funds transferring prisoners out of Guantanamo to the U.S. mainland has limited our the governments ability to take advantage of the more efficacious federal criminal law system against terrorists. Thus a natural strategy of dealing with that continuing public diplomacy problem is to avoid the addition of new prisoners while slowly decreasing the number of prisoners through working out secure ways to transfer them to home countries.

Essentially the traditional effective tools for handling prisoners: prisoner of war camps or the U.S. civilian system, do not appear to be viable given domestic U.S. politics and the mixed solutions failed badly during the Bush administration. I think the Nuremberg model hasn’t been adopted because there’s no clear victory or end point to the wars. We now see some indictments for leaders in on going international law violations, but we’ve seen relatively little action on that front until the conflicts in question have ended.

(Usual foreign policy caveat: Speaking for myself and not my employer).

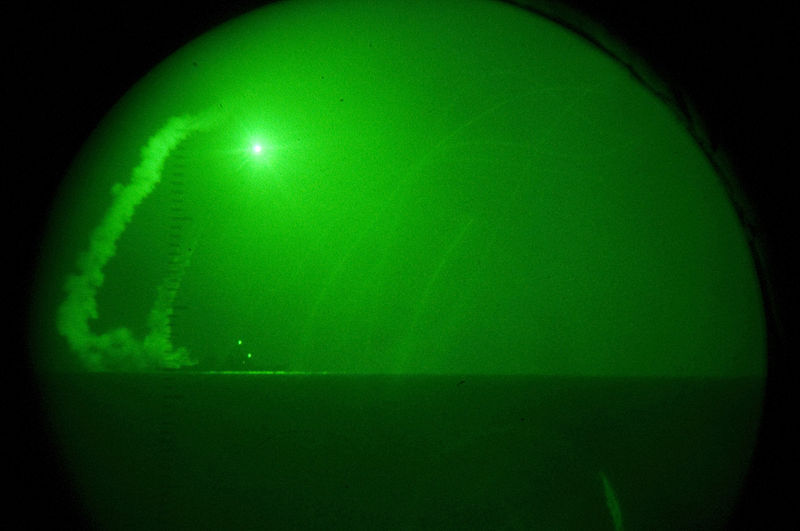

In my mind the most obvious reason for the recent US practice of killing enemies is simply one of capability. The United States only had the option of capturing and subsequently trying bin Laden because he was the target of an enormously complex and risky operation to land Special Operations Forces on his doorstep. Less important targets like al-Aulaqi don’t merit these risks so, from the American’s perspective, the only option for removing them is a drone strike. Gaddafi’s death was a similar story – the French and American air assets far overhead had no real ability to guarantee he survived capture.

ok, I’ll be the realist. the answer is preponderance. trying one’s enemies is the recourse of a power that cares a lot about its image. During the Cold War in the backdrop of a contest between ideological alternatives, image mattered more. This is not to say the US (or the USSR) acted more ethically (as a realist how would one expect this anyway?), but it is to say that image was relatively more important. How one treats their enemies is a part of that equation. Post-cold war, the preponderance of American power, combined with the absence of balancing (don’t anyone say “soft” balancing), means that the US should prefer efficiency over process for the sake of process. In short, the US just really doesn’t need to try its enemies, and if you’d rather not have them wandering around on their own, then….well….

Maybe that’s why the Afghans have started killing our men and it doesn’t take a drone, just a bullet or a woman. I guess they feel they can send us packing-again. If there’s one thing we do well it’s packing up and leaving, mission unaccomplished.

Drones may seem clinically detached, but our guy kills from afar, often including innocent civilians, but hey they all look the same. We don’t. Then the lucky “player” goes home to his or her children.

And it cuts out urinating on the bodies, we shoot from home. What have we become?

More vulnerable, that’s what. So Obama and Clinton’s goodwill tour, sorry about abusing your religion. Why not abuse ours, instead of turning nasty. Cartoons of the Virgin Mary, Or Moses, or even Mr Smith. That’s fair surely? We have more burial services than any other kind, it’s a funny religion, ours.

Technology is such that drones will be a bigger threat than the nuke. With that amount of drugs flooing our market we will pay for the enemy’s drones. So for them, it’s free, uses existing facilities, and it makes War of the Worlds look more achievable.

I’m not sure that in the three cases cited above – Saddam, Qaddafi, and OBL – we are necessarily experiencing a trend whereby the U.S. wants its enemies dead. Saddam was captured alive by U.S. troops and then handed over to Iraqi authorities, who rightly claimed and were given the role of deciding the fate of the dictator. For the Bush administration, the handing over fit well into their self-proclaimed altruistic policies of nation building and democratization. I don’t think the U.S. really cared whether Saddam ended up with a noose around his neck or behind bars for the rest of his life, so long as the decision was made by Iraqi authorities. In this case, I would in fact argue that the U.S. did care about its image, contrary to the argument posited by Anthony. Had Saddam died at the hands of the U.S., the death could have further stoked already intense opposition to the war in the Middle East and beyond. The same rationale could be used to explain the case of Qaddafi, albeit under slightly different circumstances. But again – it would be in the interest of the U.S. and NATO more broadly to relinquish the fate of yet another dictator to those he brutally suppressed for decades. Much like the U.S. decision to hand over Saddam to his own people granted Iraqis a role in determining the future of their oppressive despot and of their country by extension, the decision to allow rebel fighters to capture and kill Qaddafi is concordant with the spirit of the Arab Spring.

The case of OBL is the most disparate of the three, and brings to my mind the debate over the by now well-established U.S. policy of targeted killing. The difference here between how the U.S. dealt with its enemies after WWII and during the Cold War is perhaps best explained by looking at the changing nature of political conflict and the enemy itself, i.e. from state to sub-state. Drones strikes are a predominant counterterrorism weapon in both “hot” and “cold” war zones, and are shrouded in controversy because there is neither an international nor a national legal framework that explicitly justifies such actions. But if the individual in question truly does pose an immediate threat to national security – as individuals such as al-Libi and al- Awlaki have been reported to – what options does the U.S. really have, save relying on the tenuous (or nonexistent) capacities of local law enforcement in places such as Somalia or Yemen? Further, the ensuing rage and violence ignited by a publicized trial of a persona such as OBL perhaps plays a role in the decision to kill rather than capture. In my opinion, and in the context of terrorism, the U.S. wants its enemies dead because it’s just easier, and until now there is no proven legal basis to deny it the right. It’s a tacitly accepted policy, but it certainly carries its risks.

I agree that placing our opponents on trial is no longer as appealing an alternative as it used to be. For example, regardless of whether such fear is warranted, policymakers may wish to suppress a hostage’s ability to make a public statement to his or her supporters during a trial. There may also be less intelligence to be gained in capturing and interrogating a terrorist opponent or the ousted leader of a rogue state than in doing the same to a sitting state official. Third, American policymakers may determine that they are less likely to strike a mutually-beneficial bargain with terrorist opponents or an ousted leader than might be possible in a negotiation with officials who had until their detainment continued to wield power within their state or who could credibly convince their supporters to desist from conflict against the U.S. Fourth, it’s possible that officials worry that, if captured, prominent opponents could suffer mistreatment at the hands of American personnel, which could cause backlash and resentment against the United States. A killing that occurs during a combat situation – such as that of bin Laden – might also be easily explained as the result of an unanticipated escalation in a mission designed to capture the target. If so, it may be less likely to trigger international criticism than the execution of an incarcerated individual.

Capturing opponents also seems intuitively more difficult in situations in which the target is not located in a region where significant American forces can be easily brought to bear. Thus, except in extreme circumstances assassination may simply be more efficient to perform than secure-and-capture raids. It’s also possible that American preferences haven’t actually shifted, but that the ease of targeted assassinations has increased relative to capture. Furthermore, campaigns against terrorist opponents or rogue states may be less likely to end peacefully than conflicts between modern state militaries. If an extended conflict scenario is concluded due to enemy attrition, a larger percentage of the enemy’s leadership are likely to have been killed in the course of the conflict than if it had ended earlier via a peace agreement.

Finally, it’s at least worth considering that President George W. Bush felt personally aggrieved by Saddam Hussein. Similarly, Americans often characterize the 9/11 events as attacks against the nation as a whole. If they feel as though they are retaliating against their own aggressor, policymakers may be more apt to exact retribution through military conflict rather than allow a trial to occur.