By Page Fortna

Oliver Kaplan recently posted about the prospects for reaching a peace deal in Colombia when formal negotiations open later this month in Oslo. Reaching an agreement is the first hurdle, but over half of all attempts to end civil wars falter within the first few years. If peace is reached between the Colombian government and the FARC, will it stick?

I recently had the chance to visit Bogota (all too briefly) to talk about the implications of my research on the durability of peace in Colombia, and to learn a bit more about the nascent peace process. Here’s my assessment.

In a Nutshell: Structurally, this is a tough case, but there is a lot that can be done to make peace last. My strongest recommendation is to invite peacekeepers to help.

The Bad News

The decks are stacked against stable peace. The four most important structural predictors (by structural, I mean things that policy makers can’t do much about, at least not easily or in the short term) of durable peace are:

- A clear military victory for one side

- A relatively low death toll

- The absence of contraband (e.g., drugs or diamonds) financing for rebels

- War duration

Three of of these four structural predictors bode ill for lasting peace in Colombia:

- While the FARC has been seriously weakened militarily in recent years, it is by no means defeated.

- The Colombian civil war is certainly not the deadliest civil war the world has had the misfortune to see (wars in the Sudan, Afghanistan, and Rwanda have been much worse), but with a death toll estimated between 50,000 and 200,000, it is up there.

- While the extent of the FARC’s involvement in the drug trade is debated, it is clear that both it and right-wing paramilitaries — remnants of which are probably the most likely spoilers of a peace deal — have used narcotics money. Colombia has been a poster-child for drugs fueling war and war fueling the drug trade.

There is one (perverse) bright spot:

4. The silver lining of Colombia’s tortured history is that the very length of its war may help it achieve durable peace.

The implications of other structural factors (whose empirical influence is less clear-cut) are mixed: it’s not a war driven by identity divisions, and Colombia enjoys (relative to other war-torn places) a developed economy and a democratic political system. On the other hand, there has been a history of failed attempts to make peace, and Colombia’s jungles and mountains make renewed insurgency easy.

So structurally, things don’t look so good. That’s the bad news. The good news is that we know there are things policy makers can do to make peace more durable. And for some of these at least, there is serious discussion in Colombia of how to do that.

The Good News

- The conversation in Bogota is all about reaching a cease-fire and whether to do so at the beginning of talks as the FARC wants or the end as the government wants. (This is the reverse of the normal pattern, since governments defend the status quo and usually want a cease-fire as the price of negotiating over political issues, but that’s another story.) But what is really being discussed is a peace treaty that entails agreement between the Government and the FARC on the key political issues of land and agricultural policy, political participation, and the problems of the drug trade. These are agenda items 1, 2, and 4 agreed to during “talks about talks” earlier this year in Cuba. Peace treaties that settle the underlying issues are, not surprisingly, much more stable than cease-fire agreements. Of course, such an agreement might not be reached, but the parties do seem serious about it.

- The parties also seem to be thinking seriously about the types of confidence-building measures, disarmament and demobilization, and dispute resolution mechanisms that can help prevent uncertainty, mistrust, misunderstandings, and accidents from taking a country back to war.

A Recommendation: Bring in the Peacekeepers

On the other hand, my impression was that there wasn’t (yet?) much serious discussion of asking outsiders to help with these sorts of things, or with verification and implementation of the peace more generally. Norway is hosting the talks, while Cuba and Venezuela (both friends of the FARC), and Chile are all involved, but I got mostly skeptical looks when I raised the issue of international peacekeeping. To be fair, the government official leading the negotiations seemed much more open to the idea, but the framework agreement refers only vaguely to implementation and verification mechanisms “composed of representatives of the parties and society.”

If I have a single recommendation for those who want a lasting peace in Colombia, it is that peacekeepers be invited in. Peacekeeping works in myriad ways — it can help monitor the cease-fire, monitor and manage the disarmament and demobilization process, serve as a dispute resolution clearing house, take temporary control of territory demilitarized by both parties to prevent remnants of the paramilitaries or other nefarious groups (what some in Colombia refer to as “New Illegal Armed Groups”) from taking over coco production, and keep pressure on both sides to live up to the terms of the agreement. The mere fact of agreeing to and then cooperating with a peacekeeping mission sends an important signal of benign intent.

Peacekeeping doesn’t necessarily have to be done by the UN, though the UN has the most experience with it. It could be done by the OAS, it could be done under the auspices of the relatively new UNASUR, it could be done by an ad hoc group of states, or as is often the case, it could be some sort of hybrid of the UN, regional organizations, or interested states.

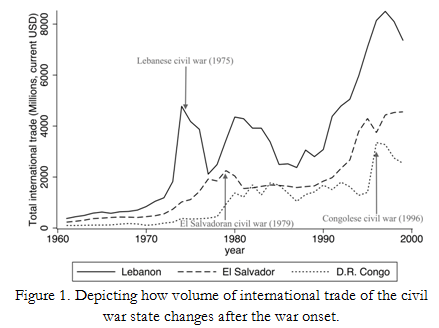

Peacekeeping is not a silver-bullet of course; it by no means guarantees that peace will last. But we know that peace is much more likely to last, all else equal, when peacekeepers are deployed than when former belligerents are left to their own devices after civil war. My research shows that peacekeeping reduces the risk of another war by up to 75-85 percent. Here’s a visual (see my book for the details):

Peacekeeping doesn’t necessarily have to entail a very strong military force, or a robust “Chapter VII” type mission. A more modest “Chapter VI” mission is often just as effective. Often peacekeepers don’t even need to be armed to make a big difference (in some cases, it’s better if they aren’t), but it is important that at least some of the peacekeepers be military personnel with the knowledge and experience that entails, and the respect that earns from government and rebel soldiers. And it would help to have enough peacekeepers to deploy throughout contested territory. But peacekeeping is perennially under-funded, under-equipped, and cobbled together in an often absurdly dysfunctional way. And yet, empirically, it still works.

I’m sure that the Colombian government would rather not have peacekeepers infringing on its sovereignty, and the FARC probably doesn’t much want monitors sticking their noses into its business. The citizens of Colombia are justifiably wary of anything that smacks of armed intervention. But it is the fact that agreeing to peacekeeping is costly that makes it a credible signal of willingness to abide by a peace agreement. And surely these costs are worth it if stable peace can be brought to Colombia.

So, to the government and FARC negotiators headed to Oslo, I say, bring in the peacekeepers, and peace be with you.

5 comments

Based on what I heard on a recent trip to Colombia, I’d say: 1. OAS already has a monitoring mission there, and it is highly regarded. I could see this being expanded under a new peace deal, but an armed PKO presence seems far fetched: Colombian officials think of their state as a capable one that has more than enough capacity to handle implementation and integration of the FARC should they agree to end fighting. The OAS monitoring mission could serve, as it has, to shore up confidence. 2. It doesn’t seem that ex paramilitaries are the most likely spoilers. Given their engagement in other more lucrative activities it seems that they couldn’t care less is FARC signs a deal with the government so long as their is no interference with their “business” operations. Most likely spoilers would seem to be dead ender guerrilla factions.

Nice analysis. I have two questions. First, I was wondering what both sides have learned from previous negotiations and how those lessons might contribute (or detract from) to the prospects for peace this time around.

Second, I imagine that the regional community should be a strong influence on both sides. You already mentioned the possible introduction of peacekeeping forces. How about the role of ALBA and other left-leaning governments in the region? Surely the international environment, at when it comes to the number of successful leftist governments in the region, is a factor that should weigh heavily on the minds of FARC leaders.

Make that three questions. Where is the US in all this? This could be the most important event in quite some time in Latin America.

Thanks