There has been a fair amount of recent discussion (see here, here, here, here, and here), inspired by President Obama’s call to debate publicly the possibility of a US intervention in Syria, considering whether the US ought to declare war on Syria. Despite the fact that the US has been engaged in many major military actions since 1945 the US has not issued a single formal declaration of war since World War II. Moreover, as I show in a recent paper, this is a global trend. In addition to debating the merits of intervention, it may be worthwhile to consider what the resuscitation of declarations of war as an instrument of foreign policy would mean:

- Domestically, a formal declaration of war activates a number of statutes that vary by country. In Georgia, one consequence of declaring war is that the president cannot be impeached. Among other things, in the US the president gains special powers with respect to sanctions, treatment of enemy aliens, and surveillance when there is a declared war. Additionally, until the passage of the 2006 Military Commissions Act, private military contractors could not be court-martialed unless their operations occurred during a time of declared war.

- Internationally, a formal declaration of war unambiguously obliges states to comply with international humanitarian law (IHL). International lawyers might respond by saying that IHL applies regardless of whether a war is declared. As a matter of law, they would be correct. From a more strategic perspective, however, states might prefer to create as much ambiguity as possible regarding the applicability of this body of law to their conflicts, especially given the growth of IHL in the past century or so. Declarations of war also activate the rights and obligations of neutrality.

- Both domestically and internationally, declarations of war could provide reasoned arguments and justifications for war, as well as a statement of war aims. Eric Grynaviski makes this point in arguing for the resurrection of declarations of war. However, as Brien Hallett has shown, US declarations of war became shorter and less well-argued before they disappeared altogether. In other words, this last function of declaring war became less relevant even when states were still declaring war.

While I agree with Obama’s call to debate the possibility of intervention (who among us does not?), I doubt that we will see a Congressional resolution declaring war upon Syria. Such a declaration would tie the hands of an administration that prefers to maintain as much legal wiggle room as possible by, for example, arguing that the War Powers Act did not apply in Libya because US airstrikes did not constitute hostilities, as well as holding back from labeling the Egyptian military’s overthrow of Mohammed Morsi a coup because doing so would affect aid the US can offer Egypt. To be clear, the Obama administration is not alone in this regard – the Clinton administration famously refrained from labeling the events in Rwanda in 1994 genocide because doing so might trigger obligations via the Genocide Convention. Indeed, the world over, heads of state appear reluctant to step over legal bright lines when it comes to the use of force. So while we might have a debate, we should not expect a declaration.

3 comments

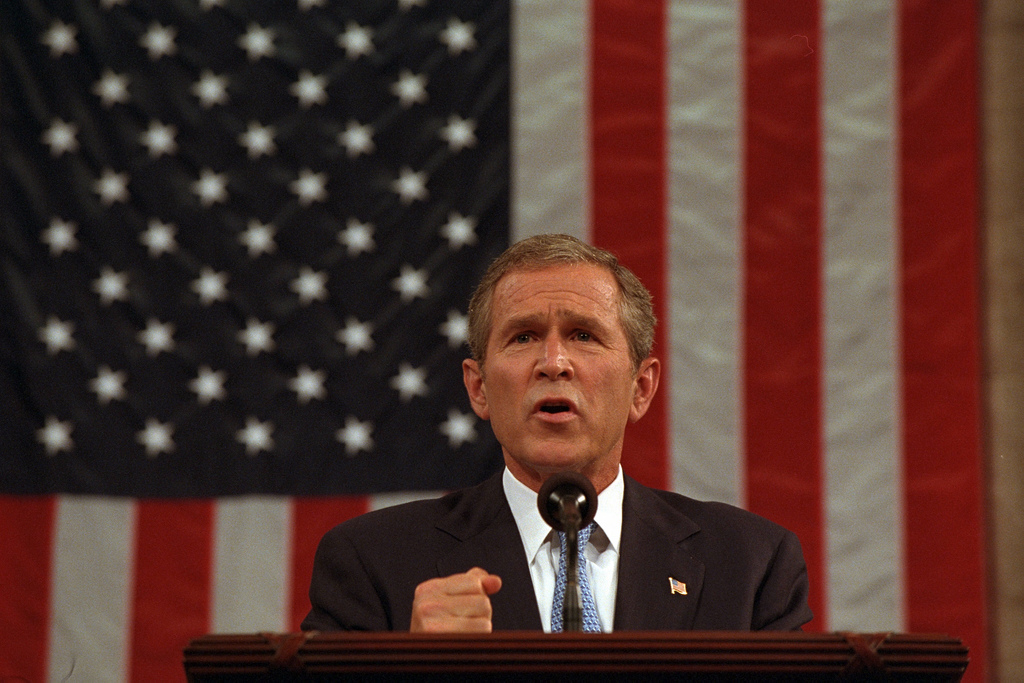

I take that statement back. If Bush even HINTED at intervention with Syria those things above would happen and whatever he hinted would be taken out of context by the media.