Do the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) and Inter-American Court of Human Rights (IACHR) actually improve the human rights performance of the countries under their jurisdiction? Given the human rights abuses documented in news sources one can hardly blame the reader for rolling his or her eyes and muttering “please” with a furrowed brow. Social scientists who study human rights are a bit less circumspect, but they are hardly Pollyannaish about the impact these courts have. Conventional scholarly wisdom about the two courts suggests that, due to the assistance of domestic judges in Europe, the ECHR has influence, but that the IACHR is a largely toothless institution. Interestingly, a recently completed dissertation turns this wisdom on its head.

Research on the impact of adverse ECHR/IACHR rulings upon governments has focused exclusively upon compliance with the ruling in that case. There isn’t a great deal of work on the topic, and interestingly, a recent study found that in the Americas country’s compliance with IACHR rulings is higher than had been believed. Yet research had yet to explore what we really care about: not whether a government responds to a judicial ruling by providing remedy in that specific case,[1] but whether it responds by improving its respect for the right abrogated in that case generally, which is to say, in its future interactions with the people in the country.

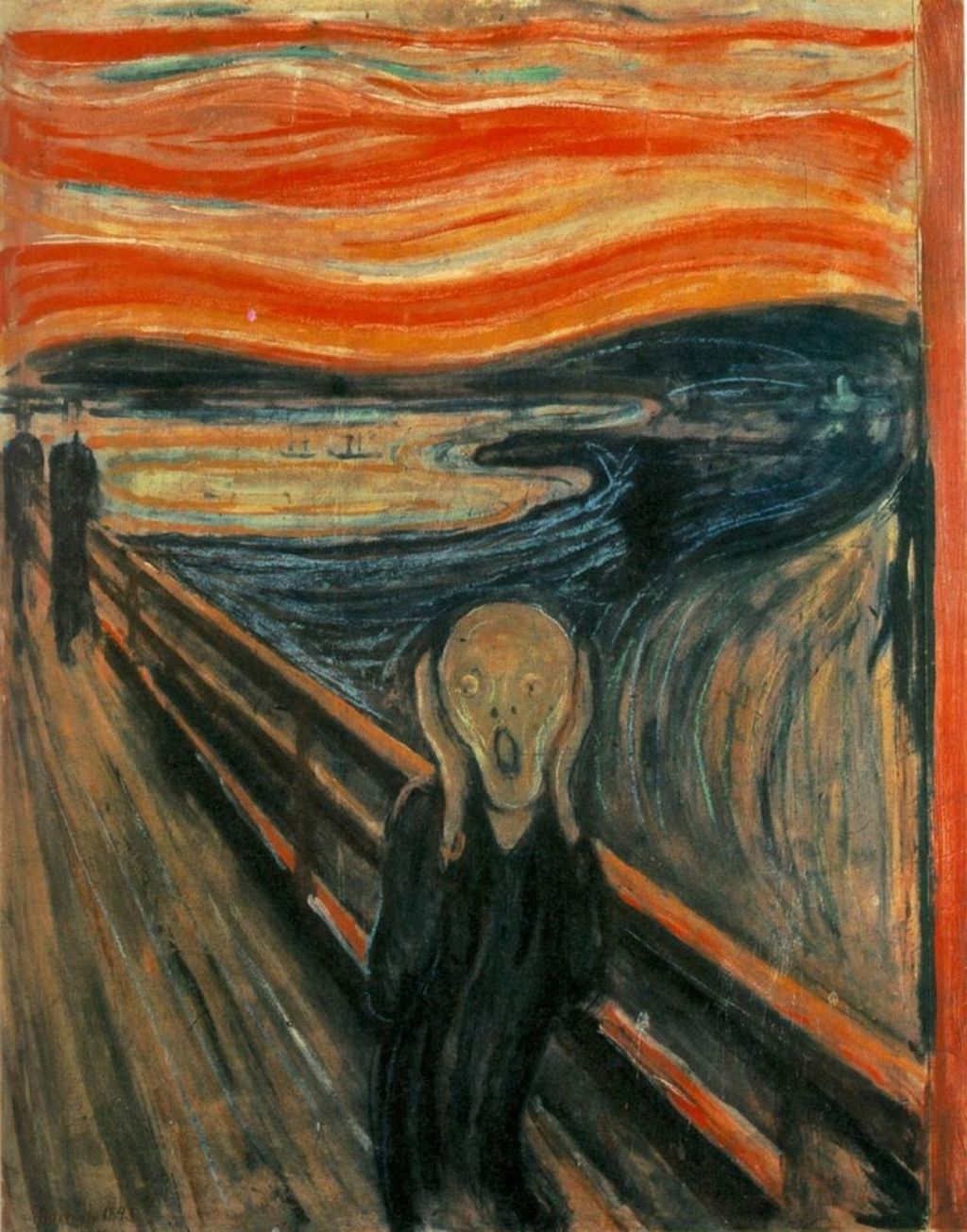

In “Domestic Implementation of Supranational Court Decisions: The Role of Domestic Politics in Respect for Human Rights”, Jillienne Haglund finds that both of these courts do positively influence country’s respect for rights, especially so when the country has a strong domestic constitutional court. Further, the impact of the IACHR is considerably larger than that of the ECHR. The figure below depicts this result. Rather than assume that the effect is constant across the countries in the region, Haglund assumes that states respond differently to court rulings, and that is why each country has its own estimate.

The figure plots the estimated impact of a ruling by the IACHR against a country for a violation of someone’s physical integrity rights (the dot indicates the average of that effect), holding all other variables constant.[2] An estimate of 2 indicates that, for a country with a very powerful domestic court, a ruling against the state by the IACHR will increase that country’s future score on the CIRI Physical Integrity scale (which ranges from 0-8) by two points (22% of its range).[3] As the figure indicates, these results are quite large, with a value of 2 or more for 18 of the 21 countries in the IACHR’s jurisdiction.

Haglund also studies the impact of rulings by the ECHR, and also finds that country’s with powerful courts respond to adverse ECHR rulings by improving their future respect for physical integrity rights (between 1981 and 2006). However, and importantly, the size of the impact of ECHR rulings is notably smaller than IACHR. Thus, in addition to finding that negative rulings by regional human rights courts have large effects upon respect for rights in countries with strong judiciaries, Haglund has also found that—contrary to expectations of the literature—those effects are larger in the Americas than in Europe.[4]

In a recent book, Emilie Hafner-Burton makes the case for a triage approach within the global human rights regime, arguing that the small impact of the human rights regime will only grow when those working for rights focus their efforts where they are most likely to have an impact. Her argument strikes me as quite sound, but I also believe that the regime has had more of an effect than we yet recognize. Haglund’s research helps illuminate the causal mechanisms that underpin what Kathryn Sikkink recently labeled the global justice cascade, and suggests that optimism about the regime may not as Pollyannaish as we tend to believe.

@WilHMoo

[1] For the victims in the case being litigated the government’s compliance with the ruling has primacy. But for society, whether government respects rights more broadly is more important. [2] The results are estimates from a linear multi-level Bayesian model, and thus the coefficient estimates represent the expected impact on Y of one unit increase in X, holding the other variables in the model constant. The analysis includes all IACHR rulings that involved physical integrity rights violations (new data coded by Haglund) during the period from 1989-2010. [3] Equivalently, we can say that when the IACHR rules against a country, if we then change that country’s courts from very weak to very powerful the future expected level of respect for physical integrity rights (as measured by CIRI) will increase by two points. The coefficient is the multiplicative interaction of two variables, a binary indicator of whether a given court case found in favor of the government (scored 0) or the plaintiff (scored 1), and a continuous measure of the power of the domestic courts that ranges from 0 to 1. [4] Haglund’s study cannot both find such an effect and explain it (except in a post hoc sense). Instead, future studies will have to be designed to explore why the IACHR has had a larger impact on country’s respect for physical integrity rights than the ECHR. Both Haglund and I suspect that the fact that respect for such rights is considerably higher, on average, in Europe than the Americas likely plays some role in the finding (i.e., there is more room for improvement in the Americas than in Europe).

0 comments

As in, for example, Serbia, human rights courts and so on will apply only to those whom the ruling classes of important powers have decided to target. By applying ‘triage’ as suggested above, the human rights activist will simply serve those powers, at least as long as current political arrangements remain as they are. I think this fact should be recognized regardless of how inconvenient it may be.

The whole genocide thing might have had just a bit to do with their decision to prosecute some former officials from Serbia.