Guest post by Javier Argomaniz and Orla Lynch

Last June, the UN General Assembly carried out their latest review of the UN Counter-terrorism Strategy. During the discussions, Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon reminded attendants in a personal statement that ‘far too often, victims are left to suffer in silence as the world around them moves on’. Mr. Ban’s intervention is telling: it shows how ensuring support for victims of terrorist acts has become a growing priority for the organisation.

Regardless of this development, victims of terrorism remain peripheral to the academic research on terrorism. We believe that the exclusion of victims impacts on our ability to understand terrorism as a complex phenomenon; due to a lack of understanding of the process of victimisation itself, but also due to the significant implications for post-conflict initiatives. In recognition of this we have recently published an edited volume that focuses on how best to understand the needs of the victims of terrorist attacks and whether/how these needs are or can be adequately met. Based on the work of two multidisciplinary research teams based in Spain and UK, our project involved an in-depth comparative analysis of the experience of victims of terrorist violence in these two European states.

The choice of these two cases is far from arbitrary. Both countries have had a long history of ethno-nationalist violence and have also suffered the impact of high-profile jihadist attacks on their soil. The legacies of violence in both states have created a large population of victims, many of whom have become a formidable political and social force both nationally in the UK and Spain and regionally in the EU.

In effect, victims organisations in the UK and Spain are a product of the context to the violence they suffered. What we found in our research is that diverse socio-political trajectories in these two European states have led to different notions of victimhood, different representations of their experience and a different relationship between types of victims. They have also resulted in two distinct models of victims support, what we have described as micro and macro-frameworks. A micro framework relates to the treatment of victims at the local level, using a victims-centred approach where the individual experience of the victim takes centre stage. Meeting needs in this instance is a bottom-up project that uses local resources but is backed up at the national level by financing and legislation. This approach is predominant in Northern Ireland.

On the other hand, the macro framework is characterised by having a strong overarching political dimension. We witnessed this in Spain where victims groups, after decades of being ignored by the political establishment, have created a rich network of associations to protect their rights. By publically campaigning and lobbying Spanish and Basque authorities for the recognition of their needs, they have pressurised public bodies to gradually develop an institutionalised, top-down and relatively well-funded system of support. Importantly, in this instance there is a dominant narrative that unites the major victims organisations and this narrative prioritises the innocence of victims, their pro-rule of law stance and their rejection of violence in any form.

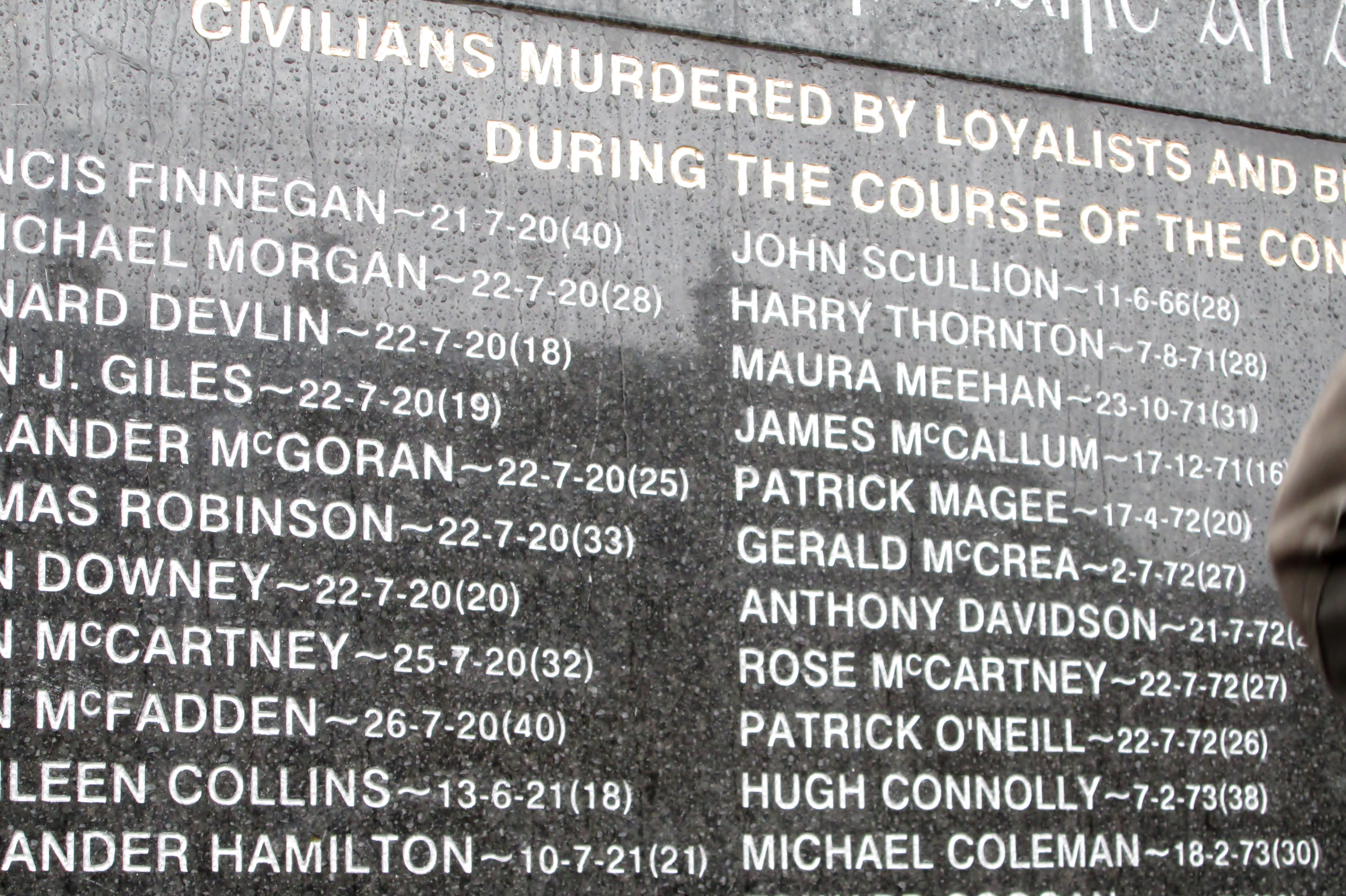

These findings are important for two main reasons. Firstly, because as national and international actors increasingly recognise, victims matter. Not only for moral and ethical reasons but also because of the important role they can play to prevent violence during periods of hostilities and in a post-conflict environment. In essence, victims’ individual stories can serve to delegitimise political violence by making the costs of the conflict visible to combatants and the wider society.

Understanding victims and victims’ organisations is also important as victims of terrorism and political violence are increasingly seen as essential actors in peace and transitional justice processes across the world. We see this in Colombia where reparation for victims has become a central point in the negotiations between the government and the FARC and where victims associations have become deeply involved in the peace process.

Secondly, our study shows that there is no ideal model of victims assistance that would work in every context. The main reason why a micro-framework has emerged in Northern Ireland is due to the persistence of a divided society and the absence of a dominant victim identity. Conversely, in Basque Country the large majority of victims were caused by ETA so this has facilitated a strong single narrative that frames needs according to a distinct political discourse.

So, on the one hand, it is still possible to argue that there are universal needs for victims: both individual (health care, psychological assistance, financial compensation) and public (public remembrance and social recognition of their suffering). On the other hand, our research has shown that understanding victimhood in cases of terrorism and political violence must involve an appreciation of the context to the violence, the politicisation of the conflict and, by extension, its victims; and the national and international narratives that support or supress the victims’ organisations agenda.

Javier Argomaniz is a lecturer in International Relations at St. Andrews University and Orla Lynch is a lecturer in Terrorism Studies, also at St. Andrews.

UPDATE (10/20/2014, 1:08 PM EST): This is a new and significantly altered version of the original post, which was accidentally published before the authors had the chance to fully revise their draft.

1 comment