By Devin Finn for Denver Dialogues

Today marks the six-month anniversary of the massacre of 152 Pakistanis–133 of them children–at the Army Public School in Peshawar, in the Northwest Frontier province. On December 16, Taliban gunmen went from class to class, firing at students’ heads. Approximately 120 people were injured in addition to the casualties. The remarkable brutality of the targeted attack spurred attention to the security of the most vulnerable.

On Friday, April 24, 2015, unidentified gunmen shot activist Sabeen Mahmud, who had just hosted an event called “Unsilencing Balochistan” in T2F, her bookshop café in Karachi and a rare space for discussion of social and political issues. In Pakistan, talk of forced disappearances and human rights abuses in the huge and embattled province of Balochistan is off-limits, and Sabeen paid with her life.

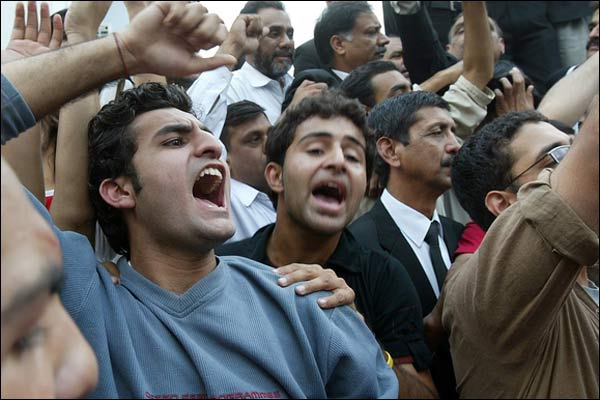

In a plural, fractured nation where mass social movements are unusual, some Pakistanis are investing in a kind of “everyday rebellion,” organizing within a space that is distinct from the work of foreign-funded NGOs and the countering violent extremism agenda. Nonviolent organizers and protestors claim that state institutions, the military, and political parties have failed to protect citizens and hold non-state actors accountable for their involvement in violence. Pakistani activist and lawyer Jibran Nasir demands that the Pakistani government make its list of banned terrorist outfits public and enforce it–shut down the offices, rallies, and hate speech of these extremist groups. Organizers argue that institutions must be held accountable for their “collective silence” in the face of terror and violence against civilians and are working to catalyze this civil rights movement.

The movement’s explicit political content sets it apart, as does the objective of making ordinary citizens aware that terrorist groups have made inroads in society, relying on religious invocation to persuade supporters. Nasir’s aim is to make it known who the terrorists are, including publicizing violent groups’ links to electoral contestation and direct support for political parties. This requires building a civil society that can generate awareness among ordinary people.

There are real obstacles to achieving the movement’s goals: the formidable level of risk that individuals’ participation in street activism entails; false propaganda circulated against civil rights activists; and the movement’s limited resources to counter disinformation.

I asked an activist and a researcher to provide their insights on the politics of nonviolent activism and violence in Pakistan. You’ll find excerpts of my conversation with contributors Syed Ali Abbas Zaidi, founder of Pakistan Youth Alliance and executive director of HIVE [Karachi], and Mubbashir Rizvi, Assistant Professor of Cultural Anthropology at Georgetown University, below, and a complete transcript here.

FINN: What is the nature of resistance to violence led by civil society and domestic activists in Pakistan? Is this a concerted, coordinated effort, and what does participation in these efforts by ordinary Pakistanis look like?

Ali Abbas Zaidi: Resistance to violent extremism in Pakistan has many forms. It includes a broad set of activities like protests, online campaigns, workshops, study circles, cultural events, seminars, and so forth. It also includes intellectual and theological resistance to extremist messaging as well.

It is not a concerted or coordinated effort. After 9/11, due to heavy foreign funding, a lot of NGOs have sprung up in Pakistan. Each organization brings with it its own interpretation, interests, and methodologies. A broad-based social movement representing the different strata of civil society has not yet sprung up, which proves the point.

[The] ordinary Pakistani is aware of how violence affects him/her and society but ideological confusion, obfuscation by the media, the political process, and personal commitments prevent them from joining a focused movement challenging extremism. The “foreign funded” NGO- conspiracy theory also runs rampant in the masses which prevents them from owning many organizations and their ideas.Mubbashir Rizvi: Historically, there have been few coordinated and concerted efforts by civil society to tackle violence at the national level. This is due to the fact that Pakistan has been ruled by military dictators and unelected bureaucrats in its formative years (1947-1970) and in every subsequent decade. This ruling elite distrusted mass-democracy and socialist alternatives that were popular with civil society activists and leftists at the time. The Army’s shadow continues to hang over key governmental policies and priorities.

The state’s failure to cultivate a coherent and inclusive national identity has prevented a broad national consensus and collective national identity. Muslim nationalism has been used as a unifying symbol for the creation of the nation-state. The ambiguity of Muslim nationalism is highlighted by the state’s use of Islam as a foil against land reforms, democratization, vernacular languages, and recognition of ethnic identities, which created a wide sense of disenfranchisement. Looking back we can see courageous efforts by activists, writers, and intellectuals to redefine Pakistan’s state narrative away from militarism and religious chauvinism.

Currently, there is a small vibrant network of civil society organizations, NGOs, and political organizations dedicated to non-violence, dialogue, and promoting peace in Pakistan. So far these efforts have had little traction in bridging the violent fault lines and healing the historical injuries that exist in contemporary Pakistan. These piecemeal efforts are widely seen as too small, too distant, idealistic, and disconnected from the day-to-day political realities of ordinary Pakistanis.

However, these spaces offer a valuable place for gathering and building a larger community of committed activists. The T2F cafe founded by the late Sabeen Mahmud some eight years ago is one notable example of a cultural space that had a tremendous impact in fostering dialogue and opening up discussion in Karachi, a mega-city of some 20 million people. However, this little space of hope now struggles to carry on after Mahmud’s assassination.

FINN: How do we understand the relationship between the state and citizen–particularly the government and civil society–given the high risks of taking political action?

Ali Abbas Zaidi: The relationship between state and citizens is one of mistrust. The government only encourages CSOs [civil society organizations] that follow the national-religio-political narrative that the state endorses. Any deflection from it causes the government to harass the concerned organization.

Mubbashir Rizvi: Since colonial times the mode of governance of colonial subjects is done through indirect means. The public is slotted within an array of collective identities (ranging across caste, religion, tribe, ethnicity, regional identities), which hardened into politicized categories. These groups are governed by customary rights, and their claims are made by a political representative or an appointed chief.

Citizenship in Pakistan is not a transactional relationship between the individual and the state as much as it is a contestation among ethnic groups, religious groups and regional and linguistic groups. The lines of conflict can erupt spontaneously over a bus accident, a neighborhood spat can turn into city-wide riot as it did in Karachi in 1986. Similarly, people only get by through accommodation, lines of credit, and reciprocity. Here, most of society lives and is governed informally, outside the purview of legibility, and most people do not pay tax.

FINN: How can activists and social organizations build effective campaigns and exert leverage on the government to demand change and accountability, in the face of violent threats and impunity?

Ali Abbas Zaidi: Pakistan has fought state oppression, dictatorship and state violence many times. Brave activists have always stormed through difficult times with compassion. Activists led the ouster of General Musharraf and reinstated the judiciary of Pakistan. The current extremist threat is multi-layered, with sections of society, media, bureaucracy, army, and other state institutions either complacent or incompetent to handle it. The process is in place, but it will take time to de-radicalize the social fabric of Pakistan like it took decades to radicalize it.

Mubbashir Rizvi: The path towards building effective campaigns for progressive change and inclusive democracy requires a slow, protracted campaign to maintain and build the fragile democratic process in Pakistan. Another major ambitious project has to be the widening of social spending through expansion of public education and education-related public works projects that employ young graduates.

The disproportionate rate of national resources that are given to military hardware and personnel can be slowly redirected to larger public works projects. This can be done by slowly expanding the definition of national security to include human security. This is by far the most challenging task ahead for civilian governments to convince the Army establishment to shed its role in the political and lucrative economic sectors.

FINN: What is the role of the judicial and legal system in ensuring an environment in which meaningful resistance can take place? What more must be done?

Ali Abbas Zaidi: [The] judicial system has been breaching human rights of citizens and has been criminal in letting arrested terrorists off the hook. The activists do not trust it and do not engage with the judicial system at all. Lack of resources, corruption, allegiances with extremists, threat of being killed (within the judiciary and activists) gives rise to such an environment.

The entire judicial system needs an overhaul. It should become an independent system within the state structure instead of an instrument of deep state, state, or political forces.

Mubbashir Rizvi: The judicial system in Pakistan does not deliver justice to ordinary Pakistanis who must wade through complex and slow legal proceedings for decades. This can only happen through major tribunals for truth, justice, and accountability that might result in cultural paradigm shifts: for instance, tribunals on traumatic events in recent history of Pakistan like the 1971 war, or the murder of Benazir Bhutto.

Zaidi and Rizvi called attention to the role of the state in promoting extremist ideas and organizations. “When violence is romanticized and extremism becomes a socio-religious norm, it takes a long struggle to counter it and introduce a pluralistic ambiance to the society,” Zaidi stated. A climate of violence and impunity makes the work of activists difficult and dangerous.

1 comment

Very dangerous