Guest post by Mike Allison

A recent article at fusion.net offers an interesting account of how protestors used social media to galvanize large public protests in Guatemala. It is fairly in depth, and thus has little space for historical and contemporary context. I offer such context here.

Guatemala suffered one of the longest (1960-1996) and most intense (200,000-250,000 dead and disappeared) civil wars of the Cold War-era in Latin America. During the bloodiest 1981-1983 period, the US-backed Guatemalan government and military killed an estimated 100,000 Mayan civilians. A United Nations truth commission determined that the State committed acts of genocide during this period. (Two years ago, former dictator Efraín Ríos Montt was found guilty of genocide in a Guatemalan court before the ruling was annulled on a technicality.) After the strategic defeat of the guerrillas in the mid-1980s, four administrations entered into on-again, off-again negotiations with the leftist Guatemalan National Revolutionary Unit (URNG) guerrilla group. These negotiations ultimately led to an internationally-brokered comprehensive peace settlement, some would say a negotiated surrender (Ryan 1994), in December 1996.

Guatemalans and the international community hoped that the peace agreement would pave the way toward political, economic, and social prosperity. Unfortunately, a number of the reforms that had been agreed to in the Firm and Lasting Agreement were defeated in a May 1999 constitutional referendum. The failure of the proposed reforms undermined efforts to recognize Guatemala as a pluricultural, multiethnic and pluri-lingual nation-state. The failed implementation of many components of the peace accords (Stanley and Holiday in Ending Civil Wars) also allowed “hidden powers” (Peacock and Beltrán 2003) to capture the “democratic” state.

During the 1970s and 1980s, the military’s counterinsurgency program became increasingly difficult to distinguish from organized crime. Civilian populations were displaced and/or massacred, not necessarily in pursuit of counterinsurgency goals, but in order for military officials and local and national elites to profit from the land of the displaced (e.g., the Chixoy Dam). Military and former military, high-level government officials and members of the private sector were linked to all sorts of criminal activity, including trafficking in humans, drugs, weapons, automobiles, exotic animals, and art. These individuals were said to comprise hidden powers:

“…an informal network of powerful individuals who use their positions and contacts in the public and private sectors to benefit economically from illegal activities and to avoid prosecution for any crimes they commit. It describes an unorthodox situation where legal authorities of the state still have formal power, but, de facto, members of this informal network hold much of the real power in the country. Although its power is hidden, the network’s influence is sufficient to tie the hands of all those who threaten its perceived interests, including state actors” (Peacock and Beltrán 2003).

The presence of these hidden powers led to the establishment of a unique partnership between the government of Guatemala and the international community. Since 2007, the United Nations-sponsored International Commission Against Impunity in Guatemala (CICIG) has worked with Guatemala’s Public Prosecutor’s Office, National Police and other state institutions to tackle impunity in one of the world’s most violent countries as measured by homicides per capita. CICIG has launched over 200 criminal investigations and legal proceedings against 150-plus public officials. CICIG and Guatemala’s Public Prosecutor’s Office have worked to arrest several high profile drug traffickers and corrupt police and politicians, and to craft legislation to better tackle impunity. It even solved a murder, which turned out to be a suicide, which almost took down President Alvaro Colom (there’s a movie). While CICIG demonstrated some very important successes, it sometimes was criticized for failing to make sufficient progress on tackling the hidden powers for which it was originally intended. That has recently changed.

In April, Guatemalan authorities arrested some two dozen individuals, including the country’s current and former tax chiefs, for their alleged involvement in a tax fraud and contraband organized crime ring. The extent of the fraud easily surpassed $100 million. Investigators allege that the private secretary to the country’s Vice President Roxana Baldetti, a retired Army captain named Juan Carlos Monzón, headed the criminal network. Salvador Gonzalez, the president of one of the country’s newspapers Siglo21, was also arrested. Days later, several defense lawyers were arrested for attempting to bribe a judge to go easy on their imprisoned clients. The arrests and protests led to Vice President Baldetti’s resignation in early May. While no formal charges have been filed against her, she has been ordered not to leave the country, her properties have been searched, and her assets have been frozen.

A few weeks later, over a dozen individuals, including the president (another former military official) and vice president of the Social Security Institute (IGSS) and the president of the country’s Central Bank, were arrested for their alleged involvement in a separate healthcare corruption case. They fraudulently awarded a $15 million contract to a Mexican company, Pisa, to provide dialysis treatment and medicine to kidney patients. However, the company neither had the experience nor the staff to handle the contract. At least 13 Guatemalans died as a result. The president of the IGSS had served previously as the President Otto Perez Molina’s private secretary. Perez Molina himself is a retired general. In the days following these scandals, the Interior Minister (a former army lieutenant colonel), Environment Minister, Energy and Mines Minister (the second one in two weeks), and State Intelligence Secretary (a retired army Kaibil) also resigned under clouds of suspicion surrounding yet additional allegations of corruption.

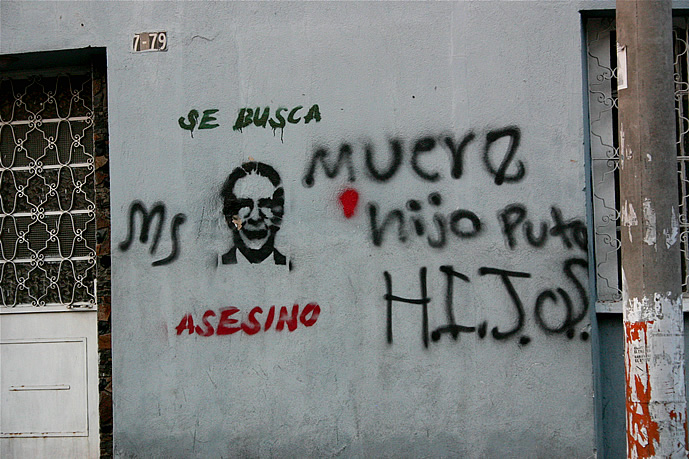

While CICIG and the Public Prosecutor’s Office are using the courts to tackle corruption in the executive branch, private sector, legal system, and the bureaucracy, the social media campaign discussed by Tim Rogers at Fusion has driven a diverse cross-section of Guatemalan society into the streets calling not only for the president’s resignation and but for deeper structural reforms. The unprecedented protests have been driven, in part, by Facebook and Twitter (#RenunciaYa, #RenunciaYaFase 2). Every Saturday for the past two months, thousands have protested in front of the presidential palace in Guatemala City. An estimated 60,000 turned out on May 16th and another 15,000 on June 13th. They were joined by protesters in Antigua, Quetzaltenango, Jalapa and other Guatemalan cities. While indigenous-led protests have occurred quite frequently outside the capital over the last few years, these protests joining people from such diverse socio-economic backgrounds are the first sustained protests of their kind in 60 years.

CICIG and the Public Prosecutor’s Office have begun to attack the illegal clandestine networks linking former military intelligence personnel and the current government, in many ways the original purpose of establishing CICIG. Their legal maneuverings have provided space for Guatemalans to take to social media and the streets to demand change, so much so that there is now talk of a second Guatemalan spring. CICIG now provides a model for other countries, not just Honduras and El Salvador, to tackle entrenched corruption.

In Guatemala’s case, it’s difficult to predict how the ongoing mobilization against corruption will end. Hundreds of citizens took to the streets on Saturday for the ninth peaceful protest. While President Perez Molina has stated that he has no intention of stepping down before his term expires in January, Guatemalans on Facebook and Twitter are calling for another massive protest on July 4th. For good reason, they are not content to simply wait until his term expires.

Mike Allison is associate professor of political science at the University of Scranton in Pennsylvania and maintains the Central American Politics blog. You can follow him @CentAmPolMike.

1 comment