By Steven T. Zech for Denver Dialogues

“Art is not what you see, but what you make others see.” ― Edgar Degas

Research on internal armed conflict focuses on insurgent groups and state security forces. However, in recent years, scholars have started to investigate the important role that other non-state actors play during and after violent conflict. Civilian groups, labor unions, businesses, NGOs, and journalists are just a few examples of non-state actors that affect security outcomes tied to conflict. One particular category of actor that merits additional attention is that of artists. How can art affect the trajectory of armed conflict? What role does art play in “post-conflict” societies? How can art affect change in contemporary social conflicts? During recent fieldwork in Peru I had the opportunity to speak with painters, artisans, musicians, and theatre groups to investigate the intersection of art and politics.

Art during and after conflict

Art is a form of creative expression that requires interpretation and invites contemplation. Art might serve as a mobilizing force and facilitate violent action during conflict. States and militant groups alike use propaganda to articulate ideologies and communicate political objectives. Collective actors can use artistic expression to define and reinforce particular social identities. Art can facilitate violence when it helps foster nationalism or dehumanize an enemy. For example, in the case of Peru, the Shining Path painted graffiti and murals in public spaces to share political messages. Shining Path militants used theatre and folk songs in remote Andean villages to indoctrinate and mobilize community members in the early years of the conflict.

Art can also serve as an important tool for peace and can foster nonviolence during and after armed conflict. Underground music movements in Lima criticized Sendero violence and denounced state human rights abuses. Painters organized exhibitions to champion peace and reconciliation. Armed conflict and increasingly authoritarian politics in Peru eventually gave way to memory and truth projects during the early 2000s. Art helped to articulate experiences in war and served as a tool of remembrance.[1] The Peruvian Truth and Reconciliation Commission (CVR) encouraged the public to revisit the past and confront the horror and atrocity from the conflict period of 1980 to 2000. As part of this process the CVR collected thousands of testimonies as well as photographic materials. The Commission released a final report and established a permanent photography exhibition at the National Museum in Lima called Yuyanapaq (to remember).

Artists, activists, and academics collaborated on other projects to invite reflection and to increase public awareness about the violent period. Installations like the “Eye that Cries” and the soon-to-open “Place of Memory” commemorate victims of violence. The Peruvian government, NGOs, and artists also encouraged communities to investigate and remember their own experiences through ethnographic drawings or traditional artistic media like tablas, retablos, or arpilleras. These works of “folk” art depict massacres and other attacks perpetrated by militants and the state security forces. Art helped to facilitate public engagement with the recent national trauma.

The renowned Yuyachkani theatre group also engaged with important political and social themes during the conflict. Members later accompanied the CVR to remote communities to help collect testimonies and communicate the Commission’s findings in “post-conflict” settings. After a recent performance of Yuyachkani’s critically acclaimed Sin Título, Técnica Mixta (Untitled, Mixed Media), I asked long-time director Miguel Rubio Zapata about the role of art in conflict and social change. He responded, “This is a question we always ask ourselves. In those years everyone thought the revolution was just around the corner, so we worked in coordination with parties at strikes and demonstrations. However, over time we began to think a little differently about power and started to work in micro-political spaces. We maintain a critical stance, responsive to individual communities, and the theatre itself was a means to change.”

Art and contemporary social conflict in Peru

The Vichama group in Villa el Salvador also worked with themes related to the conflict. At the height of violence near Lima, the Vichama theatre served as a positive force for change. During a conversation with director César Escuza Norero, he described the group’s work in the community alongside his close friend and nonviolent social activist Maria Elena Moyano. She was later murdered and blown up with dynamite in front of her children by Shining Path militants. Just days prior to Moyano’s death the director reluctantly promised Moyano that he would write a play about her efforts if anything happened to her. He recalled, “I told her I wouldn’t do it because she wasn’t going to die. She insisted and I made her the promise that I would do it. Days later they murdered her. We went through a very difficult period. The theatre was attacked two times. Many of my friends were arrested or wounded. It was hard, but we did the play. We followed through on the promise. I’ve never met a woman, a human being, so unafraid of death.” Today, Vichama continues to perform theatre that engages with pressing contemporary themes. The group’s most recent production raises awareness about the dangers of extractive industries, the exploitation of natural resources, and environmental degradation.

Performance artist Elizabeth Lino also uses art to call attention to environmental degradation. As a giant mining pit consumes her hometown of Cerro de Pasco, she developed a novel strategy to call attention to the issue. Lino adopted the persona of “Miss Cerro de Pasco” and made numerous visits to her hometown dressed as a beauty queen. She developed a critical marketing campaign, planned a tourist circuit, and has proposed nominating the mining pit as an international wonder. Lino uses art to raise awareness about environmental degradation and exposes broken promises by the state and mining companies. She uses performance art as a strategy that one might describe as “resistance through parody.” When I asked Lino about her decision to engage in this artistic campaign she explained, “I’m an artist, so I use art. I use what I know. Singers will sing. They use their tools and I use mine. Politicians use their own language in the same way. We choose a theme and use what we know to affect change.”

I met numerous painters who have spent their careers engaging with social and political themes in Peru. After working in unison with the CVR, many artists continue to give voice to victims and advance the cause of justice. For example, Mauricio Delgado creates paintings, mixed media, and virtual art projects. He works closely with the National Association of Families of the Kidnapped, Detained and Disappeared (ANFASEP) in Ayacucho. He has drawn dozens of portraits of women who demand justice for their disappeared husbands and children. Delgado explained, “In 1983 these women made demands before anyone started to denounce human rights. They made signs on flour sacks donated by local bakeries and wrote, ‘Alive you took them, alive we want them.’” He paints their portraits on the same type of sacks, sews them together, and displays the work at events in honor of their efforts.

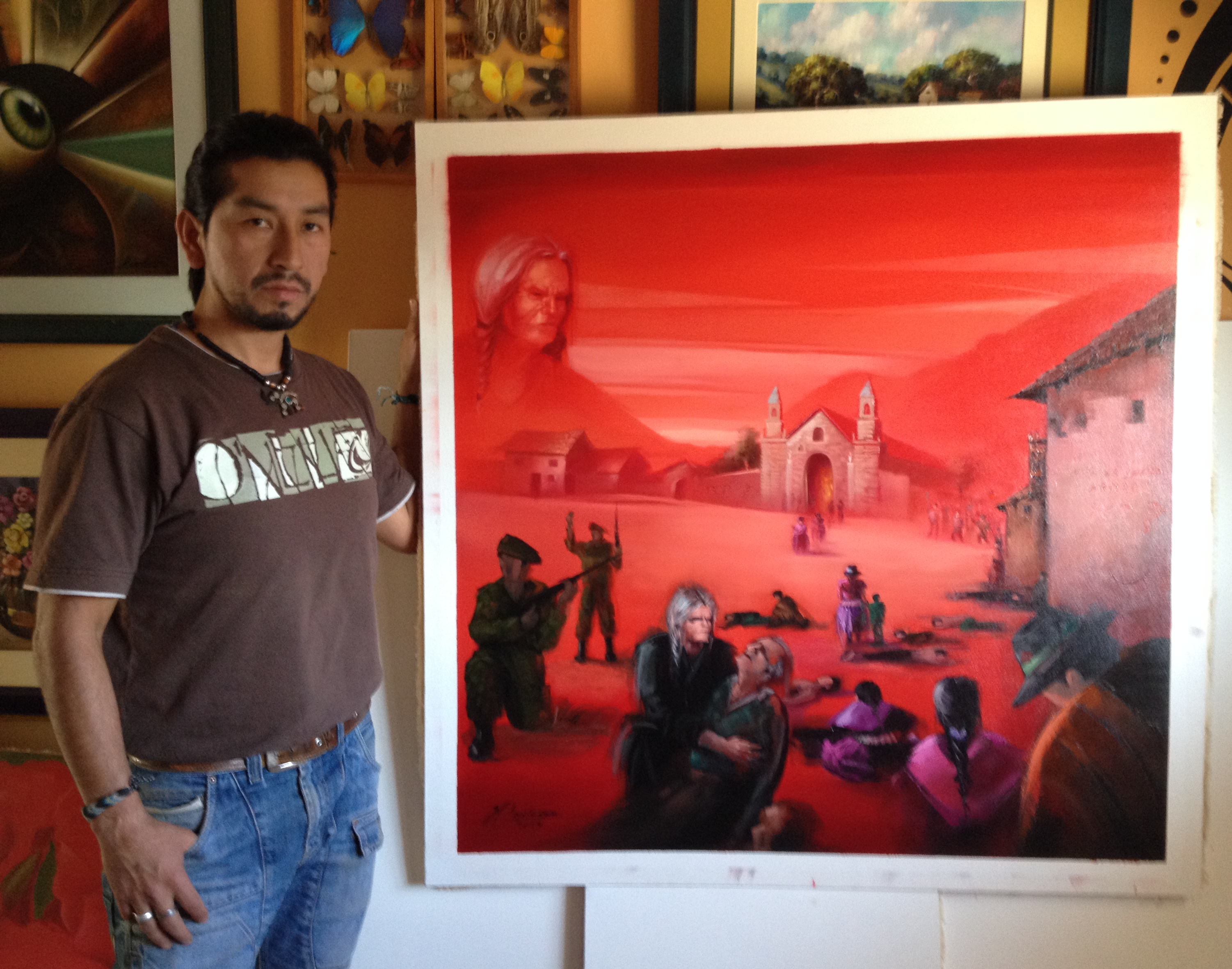

Painter Jorge Miyagui also continues to work with themes tied to the conflict period. I spoke frequently with Miyagui about the role of art in conflict. He views art as an indispensible means to social change. Art is a way to communicate important ideas and reach the people. Art has the power to foster critical awareness and strengthen community capacity to affect positive change. Miyagui, Delgado, and other Peruvian artists work together on collective projects through the Traveling Museum of Memory and the Muralist Brigade. Miyagui explained, “Art has a transformational power and projects like collective murals can open up this potential.”

The Muralist Brigade works with communities to create collective murals that address pressing local issues. For example, members recently traveled to Huamachuco to paint four murals over three days. Artists worked with young community members, self-defense force participants, and local authorities to paint murals that touched on themes of solidarity, the environment, and exploitative mining practices. I accompanied the Muralist Brigade to the San Lorenzo community in Puente Piedra, a neighborhood on the edge of Lima. Delgado, Miyagui, and Elio Martuccelli, along with students from the University of Washington, helped paint two murals that focused on the theme of children’s literacy. The artists were working with a group of children affiliated with the cultural project “Don Quijote y su Manchita.” Miyagui commented, “I believe that [these kinds of collective projects] create emotional ties and critical perspectives that are very important in politics.”

Artists play a critical and understudied role in conflict. Artistic projects continue to influence demands for truth and justice in “post-conflict” Peru and will certainly affect any contemporary movement aimed at social change. Numerous contentious political events came to dominate the Peruvian national news in May and June of 2015. Massive social protests and incidents of state repression related to mining projects in Tia Maria and other locations captured public attention. Art projects like public murals became one important way in which communities articulated their positions and made new demands on the state and private enterprise. As Peru continues to deal with conflict tied to the negative effects of extractive industries, a growing illicit drug economy, and a widespread urban crime-wave in Lima, the artistic community remains at the forefront of public dialog and collective efforts to address these problems.

[1] For more detailed examples see chapters in the edited volume Milton, Cynthia E. 2014. Art from a Fractured Past Memory and Truth Telling in Post-Shining Path Peru. Durham: Duke University Press.