Guest post by Louise Olsson and Theodora-Ismene Gizelis

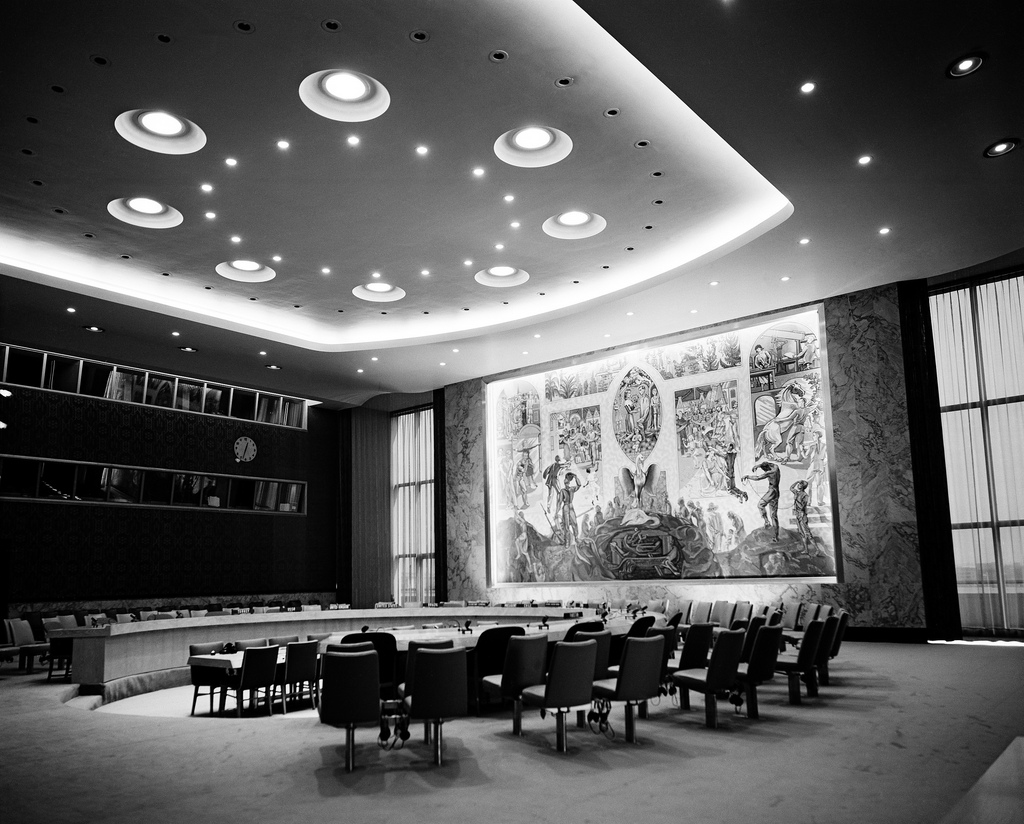

On October 13th, the Security Council will meet to hold its yearly Open Debate on Resolution 1325, the first thematic resolution on Women, Peace and Security. As the resolution celebrates 15 years, expectations are high. The day-long row of statements will no doubt contain all the correct rhetoric on a wide array of topics. UNSCR 1325 and its follow-up resolutions now cover the Council’s entire agenda and then some. As such, the Open Debate will most likely touch on issues such as prevention, mediation, extremism, refugees, peace operation effectiveness, sexual exploitation and abuse, human rights, political decision-making, social and legal reforms, and so forth. Despite this vast range of topics, UNSCR 1325 and its follow-up resolutions are often talked of as the “Women, Peace and Security agenda”. This mix of unity and diversity can prove confusing – do the resolutions encapsulate one cohesive agenda or do they constitute a common platform for a multitude of policy processes with a common long-term goal?

Historically, as Torunn Tryggestad has argued, the resolution was – to a large extent – a concession to the hard work put forth by women’s organizations to receive recognition as actors for peace. But in addition, the resolution included efforts by other actors pushing additional objectives. For example, efforts by the Department of Peacekeeping Operations to mainstream gender in peacekeeping efforts; the recognition of women in the UN system who were fighting for increased participation in peace operations; the work in the humanitarian sector to confront gender blindness; and efforts to address sexual exploitation and abuse by peacekeepers. In October 2000, all processes were merged into one (rather toothless) resolution.

Given that the resolution lacked primacy, an alliance soon formed to push its importance. As we discuss in International Peacekeeping, this alliance consisted of a range of ideologies and viewpoints that are not easily reconcilable, including both radical feminist and liberal approaches. In fact, in 2015, the alliance is still visible in the Global Study. While including the need to make peacekeeping more gender sensitive and increasing the number of women among military peacekeepers, it also emphasizes the need to decrease militarism and increase the role of women as peaceful actors.

Participation, Protection, and Gender Mainstreaming

But when we move from words to actual implementation, the question of what this resolution really is becomes sine qua non, and, hence, the alliance become more uneasy. In our book Gender, Peace and Security: Implementing UN Security Council Resolution 1325, we explore three themes of the resolution – participation, protection, and gender mainstreaming – and find that participation lags behind. A first draft of the Secretary General report correctly notes that “commitments to women’s participation…have remained largely ‘ad-hoc’ and ‘add-on’ rather than as part of a deeper situation analysis” (6/115, point 9). There also exists an unfortunate competition between participation and protection. Policy attention tends to narrowly focus on conflict-related sexual violence, often at the expense of women’s participation, despite the UN Security Council’s renewed commitment to increasing women’s participation in peace processes with the adoption of UNSCR 2122 in 2013.

As Jana Krause and Cynthis Enloe note, women’s inclusion usually results from concerted pressure by women’s civil society groups. Such activism is increasingly transnational and involves local women’s groups and international feminist NGOs (such as the January 2014 Geneva II peace talks for Syria). Participation therefore requires a different form of enforcement compared to either protection or gender mainstreaming; a bureaucratic process seeking to ensure that the central work for peace and development benefits both women and men. The latter is not least important because women’s empowerment might help lower the risk of recurrent conflict. And while the Secretary General’s draft report calls for “gender mainstreaming across all mandated tasks” (68/115, points 240 & 243), Duflo finds that there is very limited understanding on how – and under what conditions – gender mainstreaming policies can be successfully implemented.

The Secretary General’s draft report comes to the sobering conclusion that “[d]espite a robust normative framework for the advancement of Women, Peace and Security, many impediments stand in the way of the full implementation…”(67/115, point 239). Given the diversity noted above, we would argue that a significant impediment is the continued promotion of the resolution as one cohesive agenda. This engenders the idea that we can address it in one Open Debate or enforce it through one implementation plan, both placed outside of the regular work of international peace and security. This squeezes the entirety of ongoing work into a Procrustean bed – instead, we must find a way to celebrate diversity without losing common direction.

Theodora-Ismene Gizelis is a Professor in the Department of Government at the Univeristy of Essex. Together with Louise Olsson, Head of Policy and Research and Gender, Peace, and Security at the Folke Berandotte Academy, they are the co-editors of A Systematic Understanding of Gender, Peace and Security: Implementing UNSCR 1325 (Routledge, 2015).

*The opinions expressed in this blog are those of the authors