Guest post by Jessica Di Salvatore.

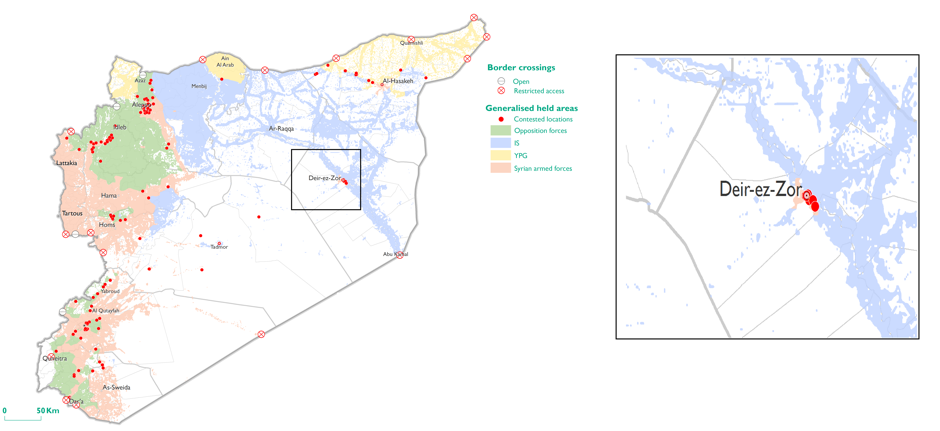

On January 16th, the Islamic State abducted 400 civilians and killed dozens after capturing the Syrian city of Deir ez-Zor. Parts of the city were enclaves of government forces surrounded by areas mostly under the control of the Islamic State. Being far away from other government strongholds and surrounded by ISIS-controlled areas (Figure 1), civilians in Deir ez-Zor were at the mercy of ISIS, which had kept them under siege for months before launching the attack. Deir ez-Zor is not an unusual case in ISIS territory. Indeed, isolated enclaves are quite common and many civilians are forced to live under siege, unable to flee. Last August, the Christian enclave of Bartella in Iraq suffered the same fate. When ISIS took Mosul, only 10 miles away from Bartella, the local population organized its defense around 600 lightly-armed volunteers. The self-defense forces could not halt the Islamic State’s advance and most of Bartella’s Christian population fled the city. Attacks against isolated minorities or pockets of opposition forces, however, are not unique to ISIS. Bayda, a Sunni majority city in the middle of “Alawite heartland” in Syria, was the stage for a pro-Assad forces-led massacre in May 2013.

The story of these and many other Syrian and Iraqi villages are the most recent instances of how territorial intermingling of groups in conflict may result in the escalation of violence, particularly against civilians. Killings in Bayda, Bartella, and Deir ez-Zor are not so different from numerous ethnic cleansings during the Bosnian conflict (1992-1995). One of the most gruesome episodes occurred in in the city of Bijeljina in 1992, at the very beginning of the war. After establishing control over the entire Bijeljina municipality located along the North-Eastern Bosnian border with Serbia, Serb paramilitary forces turned to the Bosniak population and invaded the Bosniak-majority capital where the population had gathered a small civilian resistance force. The invasion was followed by four days of mass killings against the non-Serb population. By comparing Figure 1 and Figure 2, it becomes clear how similar territorial distribution of groups in Bijeljina and Deir ez-Zor led these towns to a common tragic fate.

Why is it that armed groups in conflict use military force to cleanse enclaves of potentially enemy minorities? In a recent article in Political Geography on the role of ethnicity during the Bosnian conflict, I argue that armed groups controlling a specific region might have motivations to attack seemingly irrelevant minorities in order to consolidate control and wipe out potential opponents. Attacking isolated enclaves is also less risky because these areas might be difficult to reach and effectively protect. In most cases, attempts to resist invasion and killings come down to loosely organized and poorly armed volunteers. The need to make one’s own territory as homogeneous as possible and removing any threat to solid control becomes more pressing when co-existence of groups is not a viable option. Prior to the conflict, Bosniaks, Serbs, and Croats lived together in mixed villages where equal shares of all three groups were not uncommon. After the onset of the civil war, the increased salience of ethnic cleavages made this co-existence impossible to think of and strongly exclusionary ethnic ideologies reinforced the perception of non-coethnics as a threat to existence. ISIS’s extremist ideology and its infamous threat of “convert-or-die” suggests disturbing similarities.

The most relevant finding of my study is that violence will be more intense in areas where many minority populations are left unprotected, since large-scale killings will likely take place in order to clear such areas. Considering how fragmented territorial control is in Syria and Iraq, partly as a result of the complexity of the scenarios and the multitude of armed groups, civilians in particular are facing tremendous suffering and worryingly high risks of victimization. Under siege, unable to flee, and unprotected, they are easy targets. Protection of civilians in the midst of conflict is always a difficult task, just like in Bosnia. It could be argued that establishing protected enclaves for vulnerable populations would effectively prevent larger civilian killings, although this is not necessarily true. The creation of protected safe havens in Syria was proposed by US General David Petraeus last September, but making safe areas actually – rather than nominally – safe requires a substantial military presence. In principle, safe shelters are needed more than ever; but in practice, this translates into escalation of military action.

Consider, again, the Bosnian case. With the objective to protect civilians and provide them with security and humanitarian assistance, the UN established a Muslim “safe area” in the city of Srebrenica and then extended it to the cities of Bihac, Gorazde, Sarajevo, Tuzla, and Zepa. Lightly-armed UN peacekeepers were deployed to defend each area, but their number was exiguous and their mandate did not allow them to use all necessary means, including force, to guarantee civilians’ safety. As a consequence, the safe areas were repeatedly attacked and some of them were eventually taken by Serb forces. The most horrific event took place in Srebrenica, where the male population was almost entirely exterminated in front of helpless UN troops. The repeated violations of safe havens by both Serb and Muslim forces delegitimized the UN mission and weakened the credibility of the international commitment to peace. Safe havens, in other words, turned out to be extremely dangerous for civilians.

Identifying vulnerable locations and soft targets is crucial in order to prevent violence escalation and relieve civilians’ suffering. Particularly in Syria, civilians need protection on multiple fronts and from multiple actors as they are targeted by both ISIS and pro-Assad forces. Nonetheless, the international community needs to be aware of what safe areas would entail to be successful and how dangerous it could be to gather unprotected civilians within these enclaves. Unfortunately, the level of current involvement from the international community in Syria and Iraq is inadequate for this task and can do very little to avoid further suffering.

Jessica Di Salvatore is a PhD candidate in Political Science at the University of Amsterdam. Her current research interests include political and criminal violence, peacekeeping, and civil wars.

1 comment