By Marie Berry for Denver Dialogues

Last week the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) convicted former Bosnian Serb leader Radovan Karadžić of genocide for his role in the atrocities in Srebrenica in 1995. The court acquitted him of genocide in seven other municipalities.

The Karadžić verdict came on the heels of Secretary of State John Kerry’s declaration that ISIL is committing genocide against minority groups in Iraq and Syria.

These two events reveal the continued political salience of the term “genocide” and have renewed debates about the international community’s responsibility to intervene in foreign atrocities. They also reveal some of the complications with naming certain conflicts to be “genocide,” implicitly relegating other types of violence to the somehow less morally abhorrent “crimes against humanity”—or further still, to the problematic arena of “legitimate war.”

I’ve written more extensively elsewhere about the problems related to this “politics of naming”—to use Mahmood Mamdani’s term—but there are a few key points to note here related to these recent events.

The 1948 UN Genocide Convention describes genocide as “an odious scourge” that must be condemned by the “civilized world,” establishing genocide as violence that is evil, amoral, and barbaric. For many other genocide scholars and activists, genocide is “worse than war”; as such, they view the international community as having a moral obligation to intervene. The R2P doctrine formalized this responsibility, establishing that the international community had a “responsibility to protect” that trumped state sovereignty in the case of genocide, crimes against humanity, or war crimes.

Naming a conflict to be genocide can play a powerful role in generating international attention. Yet I reject the idea that genocide is violence that is evil or amoral, while war is considered within the normal—and acceptable—purview of state behavior (see related critiques by Mamhood Mamdani or Dubrovka Zarkov). This framing elevates the suffering of victims of genocide over victims of other forms of violence. Further, it can create a moral hierarchy that demonizes perpetrators of violence labeled as genocide, while allowing the perpetrators of other forms of violence to avoid condemnation and justice. In short, the politicized process of “naming” has allowed human-rights discourse to provide cover for political agendas and obscure the fact that, in practice, as Mamdani notes, the distinction between war, counter-insurgency, and genocide is blurred.

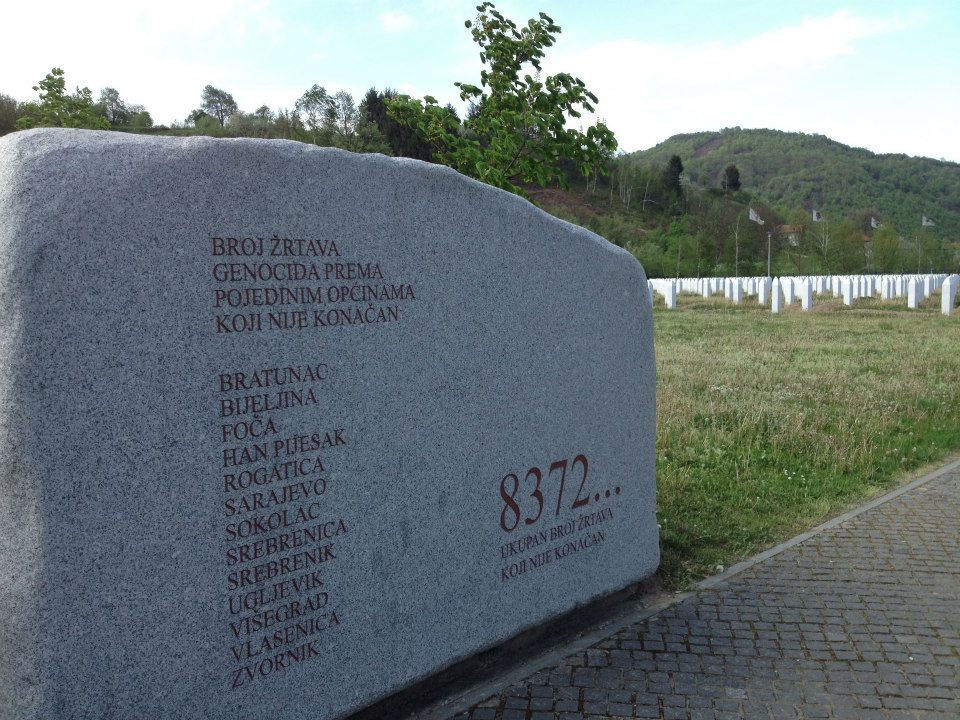

The Karadžić verdict provides a critical example of how labeling certain episodes of violence to be genocide can create a hierarchy of victimhood. Bosnian Serb forces, led by Karadžić, Ratko Mladić, and other war criminals, began a campaign of aggression in 1992 against non-Serbs in Bosnia. In the northwest region of the country around Prijedor, an estimated 5,000 non-Serbs were murdered and thousands more were sent to concentration camps where they were starved, tortured, raped, and subjected to other inhumane treatment. On the Drina river in the east, thousands more were killed, burned alive, raped, and otherwise tortured in places like Višegrad or Foča. In Srebrenica, more than 8,000 men and boys were murdered.

Yet, according to rulings by the ICTY and International Court of Justice, only the Srebrenica massacre should be considered “genocide.” This implicitly elevates the suffering of those in Srebrenica over the suffering of those in other parts of the country.

This hierarchy of victimhood has real implications for ordinary people. For example, the area around Srebrenica has received tremendous amounts of foreign aid that has been used to rebuild houses, provide urgent services to survivors, and fund the memorial pictured below. Dozens of local and international NGOs work with widows from the massacre through psychosocial therapy, job creation programs, and community initiatives (although there remains a tremendous amount of unmet need). The international attention to Srebrenica is ongoing—in July 2015, Bill Clinton, Madeline Albright, and dozens of other world leaders came to Srebrenica to commemorate twenty years since the massacre.

Contrast that with this image of Trnopolje (below), a former transit camp near Prijedor, as it looked in 2013. Or Omarska, perhaps the most notorious of the camps, which is now an active iron ore mine owned by steel giant ArcelorMittal. In short, while Srebrenica is now recognized globally, sites of other atrocities across Bosnia not considered genocide lie in disarray; local politicians in the Republika Srpska prevent the families of Bosniak war victims from erecting any formal memorials to their dead; foreign dignitaries are nowhere to be seen. Prijedor is subsumed to Srebrenica in the moral hierarchy of victimhood, and people killed in Prijedor are implicitly seen as second-class victims. This has created new social divisions within Bosnia between people from these different regions.

The politics of naming can also create a hierarchy of perpetrators. If genocide is “worse than war,” it is at least in part because it deliberately targets civilians, and particularly civilians from a specific social group. Targeting civilians is, of course, counter to the Geneva Conventions and every other “rule” of war. Yet one only has to look at the high rate of civilian deaths during wars in the 20th century to note that the targeting of civilians—or at the minimum, the acceptance of civilians as collateral damage—is a defining feature of recent conflicts, which have moved from clearly delineated battlefields to more densely civilian environments. Civilian casualties have climbed from an estimated 5 percent in 19th century wars to perhaps between 50 and 90 percent in recent wars of the 1990s (estimates are complicated; see discussion here). My point is to make clear that despite our western sensitivity to civilian casualties, we generally are less aware of the relatively higher rates of civilian casualties in major conflicts today. Indeed, civilian deaths in current wars—including in Iraq, Syria, and the Democratic Republic of Congo—are suspected to rival or outnumber combatant deaths (see evidence for this claim here, here, and here). One could argue that this makes these conflicts as morally troubling as genocide.

Mamdani provides an example of the hierarchy of perpetrators by noting the irony of the Save Darfur movement in the U.S. in the early 2000s. While college students, Hollywood actors, religious organizations, and other Americans rallied against genocide in Darfur—during which between 200,000 and 400,000 civilians were killed—perhaps 200,000 or more Iraqi civilians were dying as a result of the U.S.-led invasion. This illustrates that it is the term’s embeddedness within structures of power that allows those with power to conduct “legitimate” wars or counter-insurgency campaigns targeting certain groups, while simultaneously labeling violence committed by others as genocide. These same power holders labeled Rwanda and Darfur as genocide, but neglected to label cases like East Timor and Guatemala as such, not because they were not genocide, but because it was not in U.S. foreign policy interest to do so (or, because U.S. foreign policy emboldened or facilitated genocidal processes in these places—see here or here). As such, the term “genocide” lets perpetrators of certain types of violence comparably off the hook. By elevating genocide as the “crime of crimes,” human rights activists and genocide scholars implicitly view violence that is perpetrated by states or insurgents against civilians for reasons other than to destroy an “ethnic, national, racial, or religious group” as somehow less offensive than genocide.

This problematization of “the G-word” does not mean that organizations like ISIL are not committing genocide; they are, and it is atrocious. Nor does this discussion mean that we should not use labels when discussing mass atrocities. Instead, we should consider who has the power to employ certain labels, why they are applied in certain cases but not others, and what the ramifications of those labels may be on the lives of those directly affected. Asking how it serves U.S. interests to call ISIL’s atrocities against minority groups “genocide” but not, say, Myanmar’s persecution of the Rohingya, or widespread sexual violence in South Sudan, will begin to reveal how the term “genocide” can have normative power to compel international attention, while simultaneously facilitating the creation of hierarchies of victims and perpetrators that can minimize other forms of violence. The genocide debate in Bosnia has meant that survivors from Prijedor and elsewhere feel shortchanged by the Karadžić verdict; they are once again seen as survivors of less horrific violence than their counterparts in Srebrenica. If genocide is to remain a useful category of practice and analysis, we must pay more attention to how power shapes when, how, and why the term is deployed, and to what ends.

3 comments

A very good and rather urgent point, because genocide-talk has so often been used by the propagandists of empire. They have now almost worn the word out, while they perpetrate the crime itself when it suits their interests.

Thoughtful analysis. Thank you, Dr. Berry, for shedding light on an important topic.

Thoughtful analysis. Thank you, Dr. Berry, for shedding light on this challenging and important topic.