Guest post by Margherita Belgioioso.

On January 27 2017, President Donald Trump announced the closure of US borders to refugees and suspended the immigration of citizens from several predominantly Muslim countries. The stated aim, to keep out “radical Islamic terrorists,” echoes the rhetoric of many European politicians who have drawn a link between terrorism and immigration. From the former UKIP leader Nigel Farage, to the Italian Foreign Minister, to Prime Ministers of Hungary, Slovakia, Poland, and the Czech Republic, politicians have argued that it is time for the European Union to close its borders and perform a u-turn on refugee policy.

This rhetoric is not new. In the wake of 9/11, the European Justice and Home Affair Council issued a document arguing for measures to “strengthen controls at external borders” in response to the perceived terrorist threat. More recently, this rhetoric gained momentum after ISIS gunmen and suicide bombers killed 129 people in a series of coordinated terrorist attacks in Paris. In the midst of such heightened rhetoric, the key question has been ignored: do radical Islamic migrants actually present the greatest terror threat to the European Union (EU)?

To understand the nature of terror threats facing the EU, I filtered terror attacks recorded by the Global Terrorist Dataset (GTD) to evaluate terror attacks in member states of the European Union from the beginning of the migrant crisis in 2014. Terror attacks are defined as the threatened or actual use of illegal force and violence by a non-state actor to attain a political, economic, religious, or social goal through fear, coercion, or intimidation.

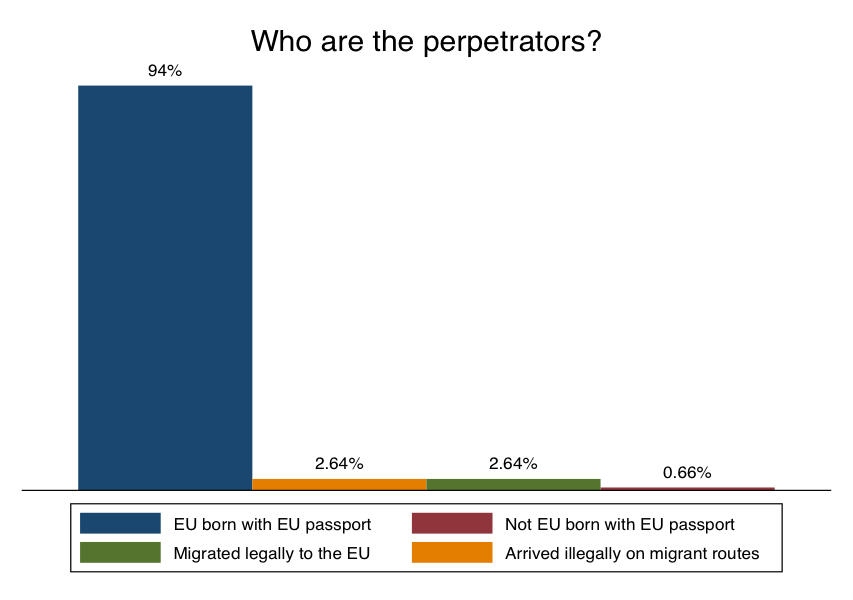

The above bar chart shows that the majority (62%) of terror attacks in European member states between 2014 and 2015 were perpetrated by European homegrown organizations (e.g., Continuity Irish Republican Army), while only 3.89% were perpetrated by Islamist organizations such as Al-Qaeda or ISIS. Almost 15% of terrorist attacks with unknown perpetrators targeted immigrants, including refugees’ centers and asylum lodgings for unaccompanied children.

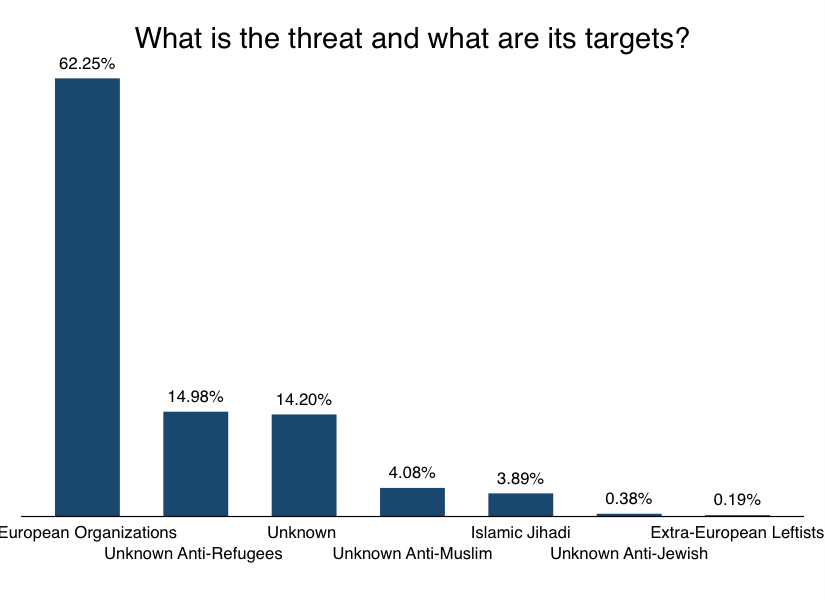

The second bar chart shows the total number of terror-related casualties by perpetrators and targets. The data reveals that Islamist organizations perpetrated the deadliest attacks in European member states between 2014 and 2015. This is followed closely by anti-Muslim unknown perpetrators and European homegrown dissident organizations. While the perpetrators acting on behalf of Islamic Jihadi organizations were extremely deadly, the data demonstrates that the vast majority of terrorist attacks –and the majority of casualties in the European member states – are related to homegrown anti-government(s) radicals and white xenophobic supremacists rather than “Islamic terrorists”. The prevalent rhetoric that sees radical Islamic migrants as the major threat to the member states is at best misleading

Where do the “terrorists” come from?

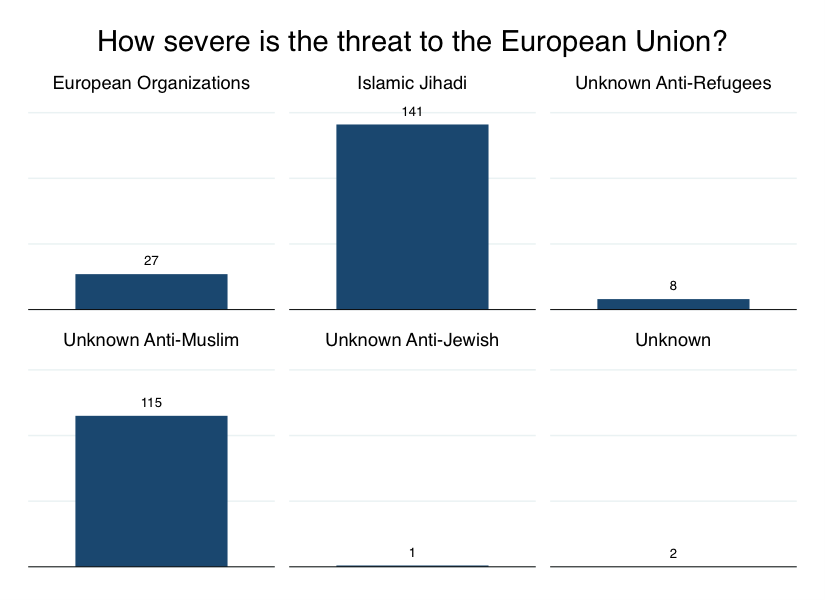

Using news reports, I coded information on the perpetrators’ nationality, residence, the modality of the perpetrators’ arrival to the EU, and whether they received military training in warzones. While it is difficult to identify who the perpetrators are using open sourced data, extant data does reveal some illuminating trends.

The third bar chart shows that 2.64% of the perpetrators of terrorist attacks since 2014 arrived in Europe illegally, while 95% of perpetrators are European citizens born in European member states. From the available information, it also emerges that only 10% of the European perpetrators of terrorist attacks travelled outside Europe to receive military training in countries such as Syria or Iraq. However, this figure is likely to be an overestimation, since the identities of the perpetrators who act on behalf of European domestic organizations are systematically under-reported.

Finally, among the individuals that perpetrated terrorist attacks in name of Islamic Jihadist organizations, 83.3% were born in Europe and possessed a EU passport, 11% arrived illegally through major migrant routes and the remaining 5.5% entered the EU legally. Thus, the data do not indicate that the terrorist threat in general – and the Jihadist threat in particular – come from the main migration routes. If anything, these descriptive statistics suggest that European member states should pay more attention to those individuals who migrate towards warzones rather than those people who flee from them.

Despite these facts, public discourse based on fear and the construction of strong ‘othering’ has a powerful effect on people. A recent survey shows that the refugee crisis and the threat of terrorism are very much related to one another in the minds of many Europeans. However, extant research indicates that migrant inflows per se actually lead to a lower level of terrorist attacks. European citizens, rather than immigrant jihadists, carried out the vast majority of terrorist attacks in the European member states from the beginning of the refugee crisis. Unfortunately, as Erica Chenoweth points out in a recent blog post, policy-makers are incentivized to react to terrorism as if the media hype about it were true. However, in doing so, policy-makers reinforce a narrative that is likely to have counterproductive effects on security by creating the social and political polarization that is the goal of groups resorting to terrorist attacks.

Margherita Belgioioso is a PhD candidate at the Department of Government at University of Essex. Her research focuses primarily on dissident tactical choices and the outcomes of mixed dissent methods.