Two weeks ago, Deborah Avant wrote that the #metoo movement could be good for men, focusing on how it provides a vehicle to address some of the ill-effects of sexualized power that have plagued the national security arena throughout its existence. Indeed, national security in general, and the military in particular, is notorious for its attempts to maintain the status quo power dynamics through a preferencing of hegemonic, and often toxic masculinity. Indeed, the importance of the cult-of-masculinity has often been the cornerstone for arguments against women’s increased participation in the military.

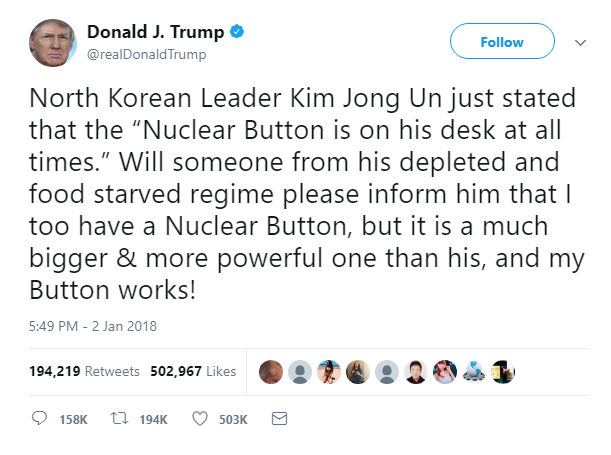

The current administration’s discussions about defense policy and strategy have provided several examples of what sexualized power and its resulting practices of masculinity look like, reinforcing the ideal type of the masculine soldier. The president recently tweeted that his nuclear button was “bigger” than that of North Korean Leader Kim Jong Un’s. In discussing the new National Defense Strategy, senior Pentagon officials have asserted that “real men fight wars, [and] like the clarity of big wars.” The rhetoric of this administration, dominated by appeals to hard power and definitive violent action, is a clear departure from the past cautions about assuming that military power was the answer to every problem.

Given the clear message from the very top that sexualized power is here to stay, the military may seem an odd place to focus on positive outcomes to #metoo. From a personnel standpoint, senior leadership has been less than open to the idea of women’s participation. The Chairman of the Joint Chiefs recommended excluding women from combat roles when he was Commandant of the Marine Corps, and the Secretary of Defense has his own checkered past with regards to beliefs about what men and women are “suited” for. Additionally, the military is still plagued by a legal system that does not allow victims of assault and harassment unbiased access to justice. However, despite the tone set from the top there have been moves within the military community by men rejecting the belief that hegemonic masculinity and sexualized power is appropriate. Scratching below the bombastic rhetoric of the national security arena, we see three areas of response to #metoo that the military as made that can serve as models for both the civilian national security community and beyond.

- Development of a Bottom-Up Alliance Network. One of the most surprising responses to the increased attention on sexual assault and harassment in the military has been the willingness of male service members–especially enlisted–to speak out against it. From TED talks to honest conversations about ally-ship, men in the military have been willing to openly have hard conversations with themselves and others about their role as being part of the problem. The public nature of these discussions is important. DoD data indicate that the number of reports of sexual assault and harassment have increased over the past decade. While this could be used to argue that the incidence of sexual harassment is up, many service women see a different picture. In focus groups with both male and female service members I conducted as part of the Defense Advisory Committee for Women in the Services, both senior enlisted and officer women stated that they were more likely to report incidences of harassment now than when they had joined. Likewise, junior service member expressed nearly no hesitation in reporting incidences.[1] Central to their reasoning was a belief that it was ok to talk about it because the majority of their peers would believe them. Many expressed sentiments that it was important now to discuss it because of the beliefs of the most senior leaders.

While in nearly every industry there are “good men” that “do the right thing,” staying behind closed doors does little to actually change culture. Remaining silent allows the status quo to endure. Especially in organizations that are still numerically dominated by men, “good men” need to speak out. The willingness of those not necessarily in positions of power to speak out is an important model for those outside the military.

- Visibility of Key Male Leaders. While the bottom-up ally network has proven important, so, too, has been the ability of key leaders to openly set the tone. Recently Scott Jensen, a retired Marine Corps Colonel with an illustrious combat record, took over as CEO of Protect our Defenders. The imagery of a white, combat-decorated Marine speaking of misogyny and toxic masculinity as a national security threat is important. Col (Ret) Jensen’s leadership forces the conversation into the mainstream. No longer can it be dismissed as a “women’s problem,” or something that liberal politicians are trying to impose on military culture.

Getting buy-in from men to combat the roots of the #metoo movement will require leaders that look like them and typify masculinity to stand up.

- Rebranding and Reframing. To combat the power imbalances at the root of the #metoo movement, the problem will have to be reframed as being beyond just sexual harassment. While sexual harassment is important, it is also easy to dismiss as a distraction. In many ways, it can be used as an argument against women’s increased participation, proving that they are a distraction and a detriment to the organizational purpose of the institution. Despite the formal focus on hard power and war from the DoD, there is encouraging evidence that the military leaders most closely related to the day to day conduct of war have become aware of the importance of emphasizing that sexual harassment is not a distraction but a detriment to the core mission of warfighting. The Personnel Studies Office (PSO) has launched a series of “unconscious bias” training for all levels of service members. At the opening of the December 2017 training, General Walters, Assistant Commandant, reiterated that this was important because “any warfighting depends on the people you fight with.”

The military is nowhere near a perfect organization when it comes to combatting sexual harassment. Nor do all military men believe that changing the culture is the right thing to do. However, despite the cultural and structural hurdles, change is beginning that can be replicated.

[1] Findings will be published in the FY17 DACOWITS recommendation report, available March 2018.