Guest post by Lise Morjé Howard and Anjali Kaushlesh Dayal

The UN Security Council’s five permanent members—the United States, the United Kingdom, Russia, France and China—are unlike-minded states with diverging foreign policy agendas. Media coverage of the Security Council typically highlights divisions between its Permanent Five Members (P5). This week, for instance, we read about Russia blocking a resolution for a cease-fire to bring humanitarian aid to a suburb of Damascusin Syria. In January, CNN declared a “big power showdown” at the Security Council.

The narrative of five great powers at loggerheads with one another, each with a unilateral veto over any of the Council’s actions, is a powerful explanation for the UN’s stasis on some high-profile issues of international peace and security. But the largest category of Security Council action—UN peace operations—does not fit easily into this narrative, and examining it should lead us to reconsider the way we think about Security Council politics. For peace operations, agreement, not gridlock, is the norm at the Security Council. In general, P5 cooperation is a vital common good, because it enables multilateral responses to global crises. When it comes to peace operations, however, the Council has settled on a puzzling, often counter-productive point of agreement.

Peacekeeping and the Use of Force

In a new article at International Organization, we demonstrate that since 1999, the Security Council has authorized all multidimensional peacekeeping missions in civil wars to use force (often to protect civilians). The force authorization breaks with previous peacekeeping practice. Peacekeeping is different from other forms of military intervention because it is based in three non-coercive principles: impartiality, consent of the warring parties, and the use of force only in self-defense. Peacekeeping is not mentioned in the UN Charter. For decades, peacekeeping missions were authorized under the Chapter VI “Pacific Settlement of Disputes” provisions of the Charter. However, since 1999, the Council has shifted to authorize all multidimensional peacekeeping missions in civil wars under Chapter VII “Enforcement” provisions.

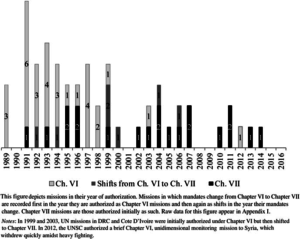

Mandates of UN Missions in Civil Wars, 1989-2016

This shift has important implications for worldwide peace and security. Today, there are more than 100,000 peacekeepers in 15 different missions, making UN peacekeepers the largest external troop presence in violent conflicts worldwide. Unlike regular military forces, peacekeepers wear blue helmets and drive in white vehicles to symbolize their non-lethal intent. The troops hail from dozens of different countries; their equipment is not inter-operable; they do not train together beforehand; nor do they consistently speak each other’s languages. Peacekeepers do not have the capacity to use force, because peacekeeping was not designed that way.

Despite the absence of coercive capacity, for decades, UN peacekeepers have succeeded in fulfilling difficult, complex mandates using nonlethal means; they have not, however, wielded force well. Use-of-force mandates incur a variety of negative effects. They undermine peacekeepers’ claims to impartiality; open peacekeepers and humanitarian workers to attack; and generate false expectations about the UN’s abilities to achieve goals by military means. Although recently some field commanders have asked to use force, and floated a new set of peacekeeping Kigali principles, no P5 member has expressed an interest or a normative commitment to have the UN develop an actual fighting capacity. And yet, all complex missions are now authorized to use force.

What explains this puzzling outcome? Why does the P5 repeatedly authorize peacekeepers to use force?

The P5 and Group Preserving

The repetition of force mandates does not stem from rational cost-benefit analysis about the likelihood of mission success, nor from organizational routines at the UN, or from a normative shift in beliefs among the P5 favoring the use of force in UN peacekeeping. Rather, we find substantial evidence that reiterated force mandates are a result of small group dynamics.

Group preserving, a term we develop, privileges the achievement and repetition of agreement over the content of the agreement, in order to maintain group status and legitimacy. The Security Council is unlike any other group in the history of international politics: its permanent members have the largest militaries in the world; it enjoys unparalleled legal authority; and its reach is global. While the members of the P5 have divergent interests and beliefs, they must cooperate regularly to produce decisions on the use of force—gridlock on more than a few matters would devalue the Council as an authoritative forum in international relations. Thus the P5 have an incentive to produce an agreement in order to preserve the status and legitimacy of their group, but no one wants to haggle over the terms of the agreement, especially in conflicts that are not of first-order strategic interest. As a result, once the P5 have agreed on a policy solution, they repeat the solution in subsequent rounds of decision-making, even when the solution may not fit well.

Agreement among the P5 is desirable from most perspectives: the Security Council was designed to facilitate cooperation between powerful countries in the service of producing solutions to complex collective problems, and to prevent the outbreak of a third World War. The repeated use-of-force mandates for peace operations reveal that the P5’s desire to strike bargains, and thereby protect the status of the Council, may sometime produce ineffective solutions. For scholars, policy makers, the victims of civil wars, and the P5 themselves, deep consideration of the mismatch between peacekeeping mandates and means may be necessary to better maintain international peace and security.