By Jette Steen Knudsen and Jeremy Moon for Denver Dialogues.

In February 2017 President Trump signed an executive order striking down Section 1504 of the Dodd–Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act that requires oil and gas companies to disclose payments made to governments for the commercial development of oil, natural gas, or minerals. The oil industry, in particular, fought to eliminate the rule, arguing that compliance is costly and erodes US companies’ global competitiveness. However, Section 1504 interacts with a wide range of other regulatory initiatives embraced by the EU and other global powers, so it remains an open question if US firms will report according to Section 1504 after the end to Dodd Frank or if they will choose to be less transparent than European firms. This begs the broader question: how do government policies affect CSR?

Government–CSR Relations

In our recent book Visible Hands: National Government and International Corporate Social Responsibility (Cambridge University Press, 2017), Jeremy Moon and I show that the significance of government action for CSR is often underestimated. Traditionally, CSR has been understood as a strictly voluntary, business-led practice and relatively little attention has been paid to how public policies interact with CSR.

In our book we suggest moving towards a perspective that appreciates governments’ agency in shaping international CSR activities. Acknowledging that CSR does not take place in a regulatory vacuum, our perspective focuses attention on the interactions between different types of public policies for CSR. More specifically, we distinguish between what we call direct and indirect public policies for CSR and their interactions.

Direct and Indirect Public Policies for CSR

Governments formulate policies that directly address specific CSR initiatives. Research by Knudsen et al. (2015), for example, suggests that government regulation of businesses’ social and/or environmental activities is on the rise and is shifting in focus, from the domestic to the international level and from softer to harder forms of regulation.

In addition, governments make policies that support CSR initiatives indirectly because they address the same issues and/or regulate the wider institutional context of these initiatives. It is, of course, possible that governments can unwittingly make policies which shape the regulatory environment for CSR. However, our present interest is in those cases where the governments make indirect CSR policies in cognizance of the respective CSR initiatives and thus where the direct and indirect policies share the same policy goal.

Case Study: Increasing Tax Transparency in the Extractive Industries

To illustrate how these different types of policies for CSR interact, we use the example of the EITI, a global standard for good governance in the oil, gas, and mining sectors. The EITI’s key aim is to increase transparency of payments made by the extractive industries to host governments in order to expose corruption and hold governments accountable for the management of tax revenues.

Direct support for the EITI has come from various governments, notably the UK, which, through the Department for International Development, first initiated EITI in 2002/2003 and administered the initiative in its early years. Since then, EITI has developed into a global multi-stakeholder initiative based in Oslo and supported by the Norwegian government. National governments have thus been key actors in initializing and maintaining EITI. In addition, the EITI has been indirectly supported by two regulatory initiatives: Section 1504 of the Dodd-Frank Act in the US and the revised EU Accounting Directive.

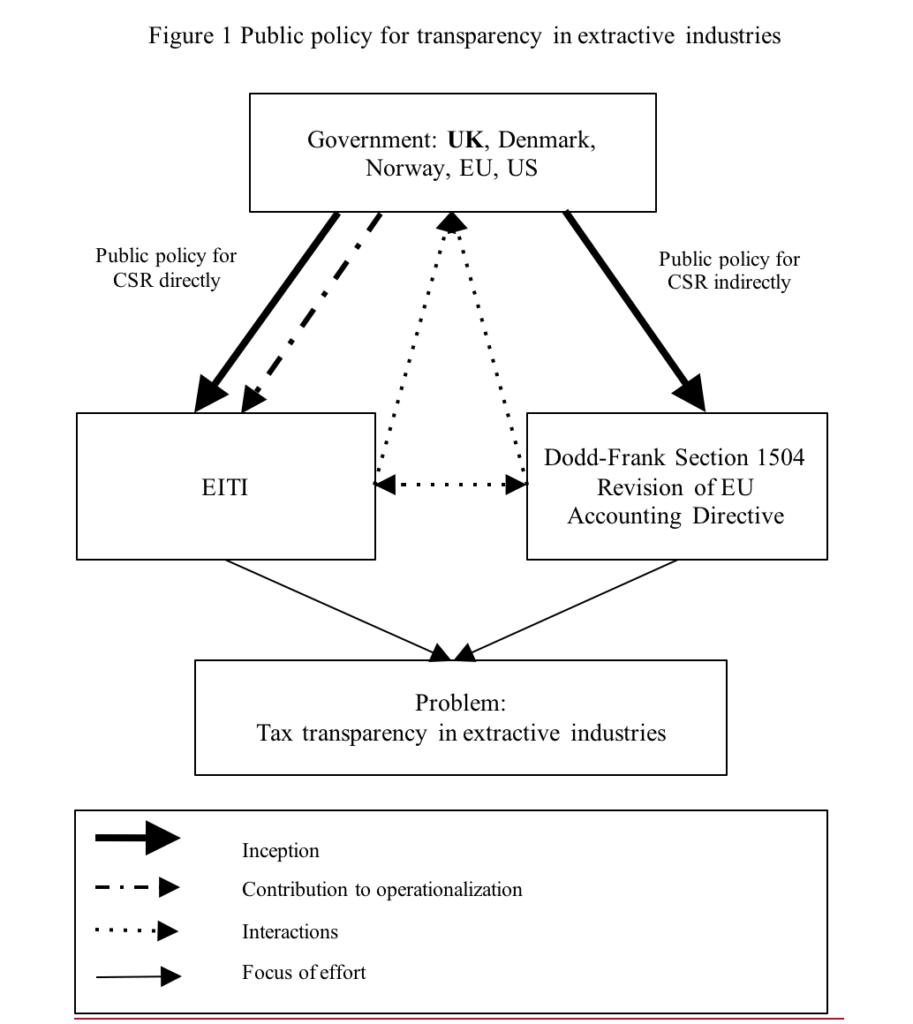

In short, a key CSR multi-stakeholder initiative (the EITI) has received both direct support from national governments as well as indirect support through regulatory initiatives, which address the wider issue of transparency in these sectors. The EITI has informed the framing of Section 1504 of the Dodd-Frank Act as well as the amendments of the EU Accounting Directive. At the same time, both regulatory initiatives have informed the strengthening of the EITI and promoted further adoption of the standard. These interactions and the ‘dual agential’ role of national governments are illustrated in Figure 1.

While our framework is useful for studying the role of governments in international CSR, a key question remains – what happens to international CSR if a strong government such as the US ends indirect support for CSR by scrapping Section 1504 of the Dodd Frank Act? Furthermore, why do governments make public policies for CSR? When do they choose to move from ‘softer’ towards ‘harder’ forms of regulation? What explains national variation? When do we see examples of conflict, tension and incompatibility?

While our book provides first steps in this direction, determining whether, when, and how CSR can make a real difference – and how government policies can support this goal – remains an important research question moving forward.

Jette Steen Knudsen is Professor of Policy and International Business at The Fletcher School at Tufts University. Jeremy Moon is Professor in the Department of Management, Society, and Communication at Copenhagen Business School.