Guest post by Roxani Krystalli.

On Monday, April 9, 2018, Colombia marked the National Day of Memory and Solidarity with Victims of the Armed Conflict. As of February 2018, according to the Colombian state, over 8.6 million Colombians were included in its Victims’ Registry. This means that roughly 1 in 6 Colombians is recognized as a victim of the armed conflict.

This day marks the second commemoration since the government signed a peace agreement with the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) to end one dimension of an armed conflict that has lasted for more than 50 years. It also marks the 8th commemoration since the passage of the 2011 Law of Victims and Land Restitution, which laid out the Colombian government’s plan for reparation for those recognized as victims of the armed conflict.

While the law has received some international praise for articulating a comprehensive approach to reparation, many have decried the ways in which some of its promises remain unfulfilled. Colombian commemorations on April 9, 2018, highlighted the ways in which advocacy communities participate in memory initiatives not only as a way to remember past violence, but also as a mechanism of demanding accountability for ongoing violations.

Further, as feminist research has shown in Colombia and elsewhere, victim advocates trouble binaries between conflict and peace, or what is framed as ‘political, conflict-related violence’ versus ‘ordinary, criminal violence.’

Finally, the commemorations underscored that memory and victimhood are not synonyms of passivity or vulnerability, but potential sites of power and politics.

Memory in the present

Victims’ associations in Bogotá’s Plaza de Bolívar highlighted that memory does not belong in the past. Rather than solely emphasizing violations that they suffered during the armed conflict, victims’ groups drew attention to violence against human rights defenders that has continued since the signing of the peace accords.

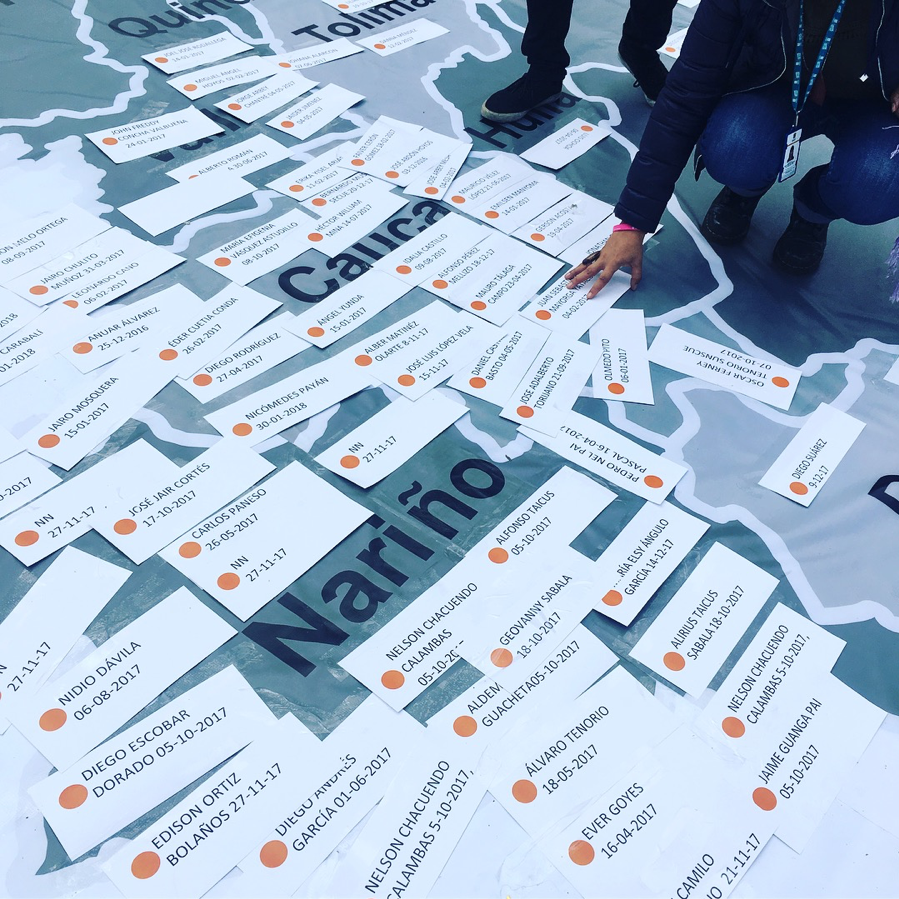

Between January 2016 and February 27, 2018, the Colombian Ombudsman (Defensoría del Pueblo) registered 282 reports of assassinations of human rights defenders. Afro-Colombian and indigenous leaders have been especially affected. These official numbers do not include threats, failed attempts, or individuals who may be afraid to report such incidents to the state.

Numerous scholars have drawn attention to the violence that remains after peace accords. These include, among other forms, violence by criminal actors (often not classified as ‘political’ or as part of the armed conflict), the violence surrounding mining or other extractive activities, intimate partner violence, or violence that continues because of a ‘socially permissive environment’ that normalized it.

Representatives of victims’ groups highlighted these dimensions in their commemorations. In one area of Plaza de Bolivar, a series of black coffins were arranged in concentric circles to mark the deaths of assassinated social leaders. “Being a social leader should not cost us our lives,” read one banner in the Plaza.

On each coffin, inscriptions in chalk contained messages that reflect key pillars of victims’ struggles: “Enough with corruption.” “Peace is a right.” “No more victims.”

These initiatives underscore the ways in which an armed conflict does not end with the conclusion of a formal peace accord. As one leader of a victims’ group in Antioquia told me in an interview in February 2018, “we are living in post-accord Colombia, not post-conflict Colombia.”

A systemic, comprehensive approach to violations

Existing feminist research on justice after mass violence underscores the need to frame violence not only as individual or with a focus on exclusively physical violations. Rather, as victims’ representatives highlighted in Colombia, structural violence and broader social dynamics of power are part of the complex web of memory and political claims in the post-accord era.

Highlighting the effects of conflict on the environment, one inscription read: “Mother earth is also a victim – when will they repair her?” Another banner declared: “Peace with hunger and without social justice is an illusion.”

Many victims’ associations, as well as poorer Colombians who are not part of the Victims’ Registry, deem that the focus of the 2011 Victims’ Law on conflict-related violations is too narrow. “I am a victim of state abandonment,” claimed an individual not eligible for inclusion in the Victims’ Registry in an interview in Bogotá in November 2017. “We live in the same conditions as victims, same poverty. Why are we forgotten?”

As these narratives suggest, peace and justice in Colombia cannot be divorced from socioeconomic realities. They require addressing the hierarchies that the conflict created and reshuffled, as well as those that originated in the legislative and institutional framework in its aftermath.

Victimhood as a site of agency and political claim-making

Some of the narratives visible in the commemorations push back against a framing of ‘victim’ as synonymous to passivity, vulnerability, or lack of agency. Instead, they showcase the ways in which the ‘victim’ label can be a site of power and politics during the transition from violence.

Many of the signs expressly named former presidents, seeking to hold them accountable for ongoing violations. “Uribe, don’t kill any more,” read one inscription on a coffin in the Plaza be Bolívar, in reference to the former Colombian president Álvaro Uribe. In the same city square, activists pinned the names of assassinated human rights defenders on a map of Colombia. One corner of the map declared the current president Juan Manuel Santos to be a criminal, while another stated, “this is the work of the Nobel Peace Prize.”

While the Colombian state has attempted to gather and communicate official statistics regarding its victim outreach, many of those who identify as victims resist this portrayal. “We are not numbers. We are people,” read an inscription on one of the coffins laid out in Plaza de Bolívar.

As these narratives show, recognizing that we cannot yet speak of the conflict in the past tense, that violence is not exclusively synonymous to physical violation, and that victims are political actors are essential for a meaningful path to peace and justice in Colombia.

Roxani Krystalli is a Peace Scholar at the US Institute of Peace, an International Dissertation Research Fellow at the Social Science Research Council, and a PhD Candidate at The Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy. She is currently based in Colombia, where she is researching the politics of victimhood during transitions from violence.