Guest post by K. Chad Clay.

Governments often use economic sanctions for the expressed reason of curbing poor human rights practices by targeted states. However, previous research on the topic (e.g. Peksen 2009; Wood 2008) has found that the imposition of economic sanctions is regularly followed by increases in the use of torture, extrajudicial killing, political imprisonment, and enforced disappearance (also known as physical integrity rights abuses) by the targeted government, even when the sanctions are imposed over the target’s human rights practices. This raises a question: if sanctions produce worse human rights outcomes in the states targeted with them, why do governments continue to use them to try to improve human rights?

There are many possible answers to that question, but in my recent article at the Journal of Global Security Studies, I focus on two in particular. First, while the imposition of economic sanctions may very well lead to increased abuse in targeted states, the threat of human rights-related economic sanctions may lead to improvements in the targeted government’s human rights practices (e.g. Drezner 2003; Lacy and Niou 2004). Second, targeted states may not be the only, or even the most important, audience for the signal sent by sanction activity (Baldwin 1985). As such, by showing observing leaders around the world that there is a possible additional cost associated with human rights abuse, rights-related sanction activity may cause some governments that were not targeted with sanctions to think twice before engaging in rights violations.

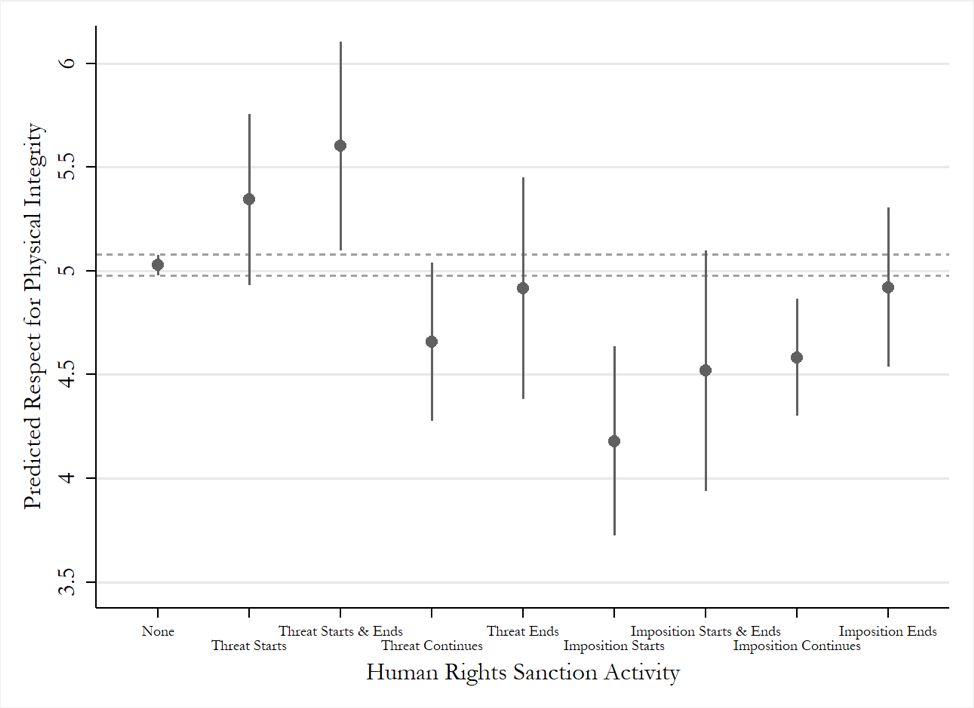

I test these arguments in a couple of different ways. First, I focus on the direct effect of human rights-related sanction activity, seeking to determine whether the predicted level of respect for physical integrity rights in a state that is average along all of the other dimensions included in my model is significantly different after sanction activity than it would be in the absence of that activity. The figure below shows that human rights sanction activity is only significantly associated with improved respect for physical integrity rights when economic sanctions are threatened, not imposed, and ended all in the same year. If sanction threats extend beyond the first year, they are not associated with significant changes in the target’s human rights practices.

On the other hand, the figure above also shows that government respect for physical integrity rights tends to be significantly worse in the targeted state in any year in which a rights-related sanction is imposed and does not end. As such, the direct positive effect of human rights-related sanction threats is lost if that sanction has to be imposed.

However, as I mentioned above, it could be that human rights-related sanction activity makes things better in states other than the targeted state, particularly if it signals that abuses in the non-targeted country could lead to similar economic costs. In particular, I argue that this is likely to happen if the state in question (1) has similar or worse human rights practices than the targeted state and (2) tends have similar foreign policies and relationships with other countries as the targeted state. In these cases, sanction activity against the target state may be more threatening to an observing leader because that activity suggests that the leader’s human rights practices have been condemned as unacceptable by the sanctioning country, and the sanctioning country is targeting states like the observer’s country, particularly with regard to their relationship with the sanctioner and the rest of the world.

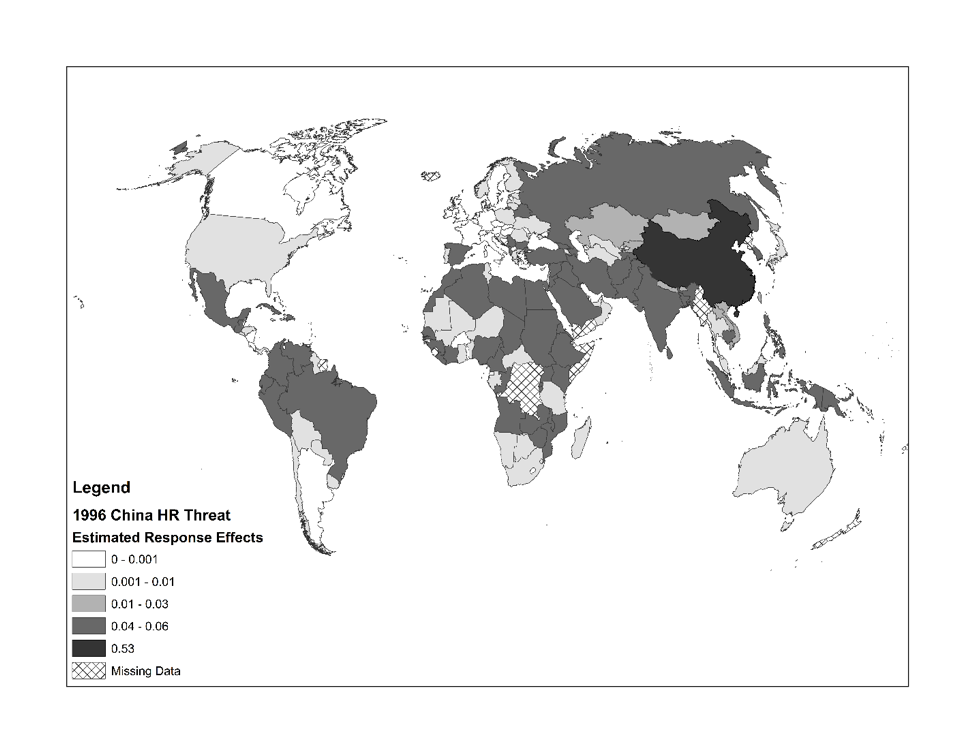

Looking at whether human rights-related sanction activity affects non-targeted states’ human rights practices, I find that rights-related threats tend to be significantly related to improvements in human rights in non-targeted states with the similarities to the target discussed above, but impositions are not significantly related to the practices of targeted states. For instance, if we look at the global estimated effects in 1997 of a human rights-related sanction threat made against China in 1996, we see that many countries are expected to have improved practices in the aftermath, as shown in the map below.

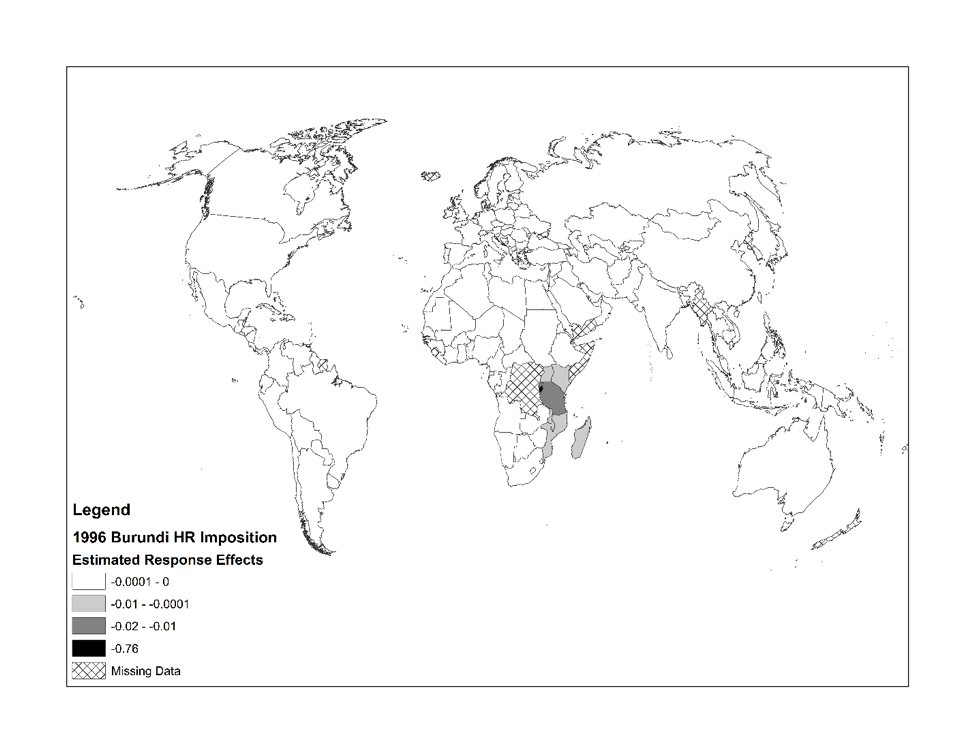

However, if we look at the global estimated effects in 1997 of a human rights-related sanction imposition against Burundi in 1996, we observe that the effects are almost entirely negative and limited to Burundi and the countries immediately surrounding it, as shown in the map below.

On a global scale, the estimated positive effects of the threat against China greatly outweigh the negative effects of the imposition against Burundi. However, no single country receives an estimated positive effect from the human rights-related threat as large as the negative effect estimated for Burundi after sanctions are imposed.

Overall, if these findings hold up under additional scrutiny from other studies, this work shows that economic sanctions may be better tools for improving human rights practices than we previously thought. However, these findings also lead to a dilemma. In order for the threat of economic sanctions to continue to have the positive effect on human rights practices shown here, those sanctions must be imposed from time to time. Otherwise, targeted governments will have no reason to fear sanctions and will not respond to threats. As such, the question of whether it is ethical to use human rights-related economic sanctions – whose effectiveness depends on periodically engaging in action that will lead to worse human rights outcomes in some locations – remains crucial.

K. Chad Clay is an Assistant Professor of International Affairs in the School of Public & International Affairs at the University of Georgia. His research focuses on the determinants, diffusion, and measurement of human rights, collective dissent, and economic development.