Guest post by Rebecca Cordell, K. Chad Clay, Christopher J. Fariss, Reed M. Wood, and Thorin M. Wright.

Last month the US Department of State released the 2017 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices. Since the mid-1970s, US law has required that the State Department submit to Congress a summary of human rights practices for all states receiving financial assistance. They have become an important tool for policymakers, activists, and scholars worldwide.

Recently, however, observers have scrutinized the reports for signals from the Trump Administration reflecting its position on human rights in the US and around the globe. The absence of any formal press conference or speech by the Secretary of State announcing the release of the 2016 report marked a striking deviation from longstanding practice. Additionally, the sections covering human rights conditions in Gaza and the West Bank and reproductive rights have been omitted from the reports.

Are these changes representative of a systematic shift in the content of the reports? In order to explore this possibility, we compare the structure and content of the 195 country reports produced in the last year of the Obama administration and the first year of the Trump administration (390 reports total). Using a text analysis process created for the Sub-national Analysis of Repression Project (SNARP), we systematically catalogue and analyze text-based data from the annual human rights reports.

Changes in Report Length and Coverage

Overall, the length of reports declined by 14% between 2016 and 2017, implying that each report now contains less information (this difference is statistically significant). The word count of the reports declined in 92% of all country reports and increased in only 8%. By comparison, the average length of the word count of the individual country reports in the first year of the Obama administration (2009) is 12% greater than the word count in the last year of the Bush administration (2008), though this change is not statistically significant.

For decades, the report for each country has consisted of a number of specific sections that broadly represent clusters of human rights issue areas. While the length of all sections decreased in the 2017 reports, the decreases were statistically significant for two sections: one for discrimination, societal abuses, and human trafficking, and the other for corruption.

This focused reduction is troubling because these sections contain information on abuses such as rape and sexual violence, domestic abuse, and discrimination based on race, ethnicity, gender, or sexuality. Because these reductions are topic-focused (and not uniform across sections), it is unlikely that the changes are simply due to the trimming of the State Department in 2017.

Changes and Implications

Given the Trump administration’s public rhetoric on policies related to women’s rights, minority populations, and refugees, we also look at the changes in how often these topics are discussed in the 2016 and 2017 reports.

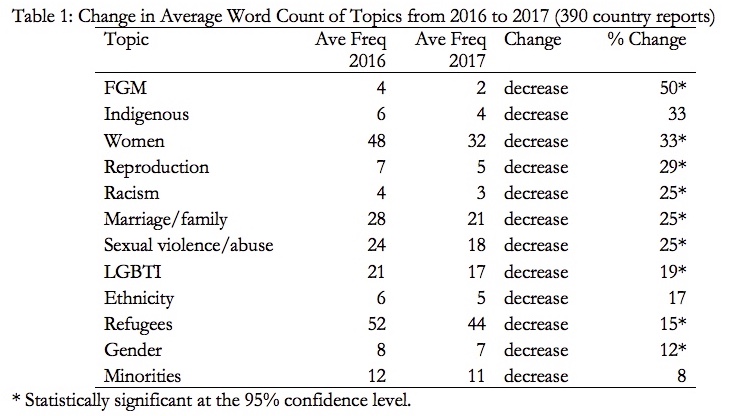

Table 1 groups associated words and a subset of topics that experience the greatest change in average word frequency from 2016 to 2017. We find a systematic decrease in the frequency of terms associated with women, reproduction, racism, sexual violence and abuse, LGBTI rights, and refugees. The average use of terms associated with women dropped by one third between 2016 and 2017. Digging deeper, we find that not only was the section pertaining to reproductive rights removed, the words “reproductive(ion)” and “family planning” were effectively eliminated in the reports (decreasing in average word frequency at 100%).

The average use of terms associated with reproductive rights drops by 50% when the terms “abortion” and “sterilization” are removed from the category – which only feature more frequently in 2017 reports because of a new passage in the majority of reports that states “there were no reports of coerced abortion, involuntary sterilization, or other coercive population control methods”. This new passage is in a small subsection “coercion in population control”, which replaces the detailed reproductive rights section.

The minimization of human rights topics previously included in the report is tantamount to trivializing these rights and represents a retreat by the US from its position as a global human rights leader. Our results offer guidance on where other human rights groups like Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, or International Lawyers for Human Rights should consider investing in additional monitoring and reporting to make up for – and directly critique – these changes.

Rebecca Cordell is a postdoctoral research associate at Arizona State University. K. Chad Clay is an Assistant Professor at the University of Georgia. Christopher J. Fariss is an Assistant Professor at the University of Michigan. Reed M. Wood as an Associate Professor at Arizona State University. Thorin M. Wright is an Assistant Professor at Arizona State University. All authors are working together as part of the Sub-National Analysis of Repression Project (SNARP), funded by the National Science Foundation (award numbers SES 1626775, 1627464, 16267101).