Guest post by Rebecca Cordell.

Following the launch of the War on Terror, the United States established a global rendition network that saw the transfer of CIA suspects to secret detention sites across the world. Conventional accounts of foreign complicity show that 54 diverse countries were involved, including many established democracies.

CIA Rendition, Detention, and Interrogation (RDI) practices would not have been possible without international cooperation. While some states hosted CIA secret detention sites, others carried out the arrest, capture, detention, and interrogation of detainees on behalf of the CIA, shared intelligence during detainee interrogations, and provided staging posts for rendition flights to rest, refuel, and regroup at their airports.

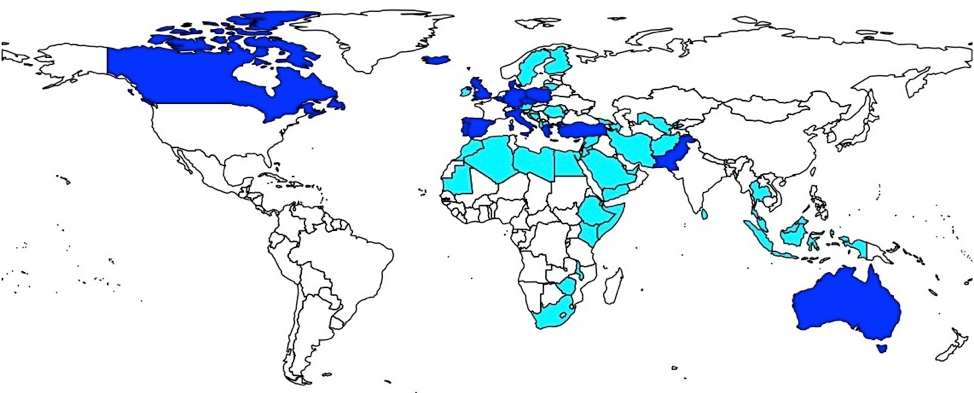

Why did more than a quarter of the world’s countries choose to participate in RDI operations during the post-9/11 period? This clandestine security coalition becomes particularly intriguing when we take a closer look at the diverse group of states alleged to have collaborated with the US (see Figure 1). For example, why did Denmark and the UK participate, but not Norway or France?

Figure 1: International cooperation in rendition, secret detention, and interrogation (Alliances).

In a recent article, I argue that the US screened countries according to their preferences on security-civil liberties trade-offs. In short, countries with similar preferences to the US on human rights would have been cheaper to buy off and would have required less persuasion to cooperate. Given the sensitive nature of RDI cooperation and a desire to maintain secrecy for as long as possible, it was crucial that the US avoided approaching countries that could decline cooperation and risk leaking controversial counterterrorism activities.

To arrive at this finding, I created a new dataset that measures international cooperation in CIA RDI using information contained in the Open Society Foundation’s report on Globalizing Torture: CIA Secret Detention and Extraordinary Rendition. To test my argument, I created a new ideal point measure of common interest on human rights between the US and partner states using United Nations General Assembly raw voting data on human rights resolutions. Voting patterns on human rights resolutions provide us with some indication of a country’s willingness to bend human rights regulations for the sake of national security.

For example, in 1999 the United Kingdom, Poland, and Romania (known RDI partners) demonstrated identical voting behavior to the United States by abstaining on a Human Rights and Terrorism resolution that included provisions on upholding human rights in the context of counterterrorism. However, in comparison, in 2000 the Netherlands and Norway (countries that did not cooperate in the RDI program) voted in support of a resolution to uphold the Geneva Conventions, whereas the United States voted against it.

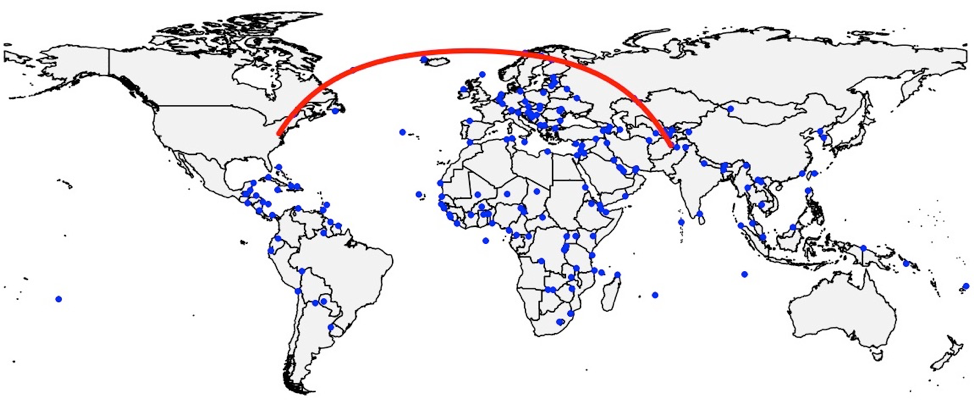

Due to the limited range of the private civilian aircrafts used by the CIA, extraordinary rendition operations included a series of stops where aircrafts could rest, refuel, and regroup during a long journey from the United States to secret detention sites located across the globe. Accordingly, we might be more likely to observe cooperation from countries with an airport closer to a central rendition transit corridor during the transfer of a detainee. To capture this, I used public flight data to model a country’s logistical utility during the transfer of a detainee based on their distance to a central rendition transit corridor between the US and Afghanistan (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Central rendition transit corridor control variable.

I find that countries with similar preferences on human rights to the US were more likely to trade-off civil liberties for national security and participate in CIA RDI. Interestingly, I find that core international relations theories fail to fully explain this form of cooperation, including the expectation that US allies should be more likely to cooperate—this is likely due to the fact that secret nature of RDI operations imposed an entirely different dynamic on alliance formation that required the US to be far more selective beyond its usual cooperation partners.

This research provides a unique insight into the causes and dynamics of cooperation on sensitive areas of international security that are often shrouded by secrecy. The results also have important policy implications, as they indicate that democracies are willing and able to abuse human rights in the name of national security when they expect these activities to remain hidden.

Rebecca Cordell is a Postdoctoral Research Associate at Arizona State University.