Guest post by The Conflict Consortium.

As readers of this blog know, the study of political conflict/violence (e.g., genocide, civil war, terrorism and human rights violation/repression) and peace (e.g., civil resistance, negotiation and community building) is extremely important. Where should graduate students go to study these topics? In order for prospective graduate students to select the right doctoral program, they need access to a wide range of information. It is often difficult, though, for potential students to locate the kind of data that they need to make an informed decision. The most widely used guides (e.g., US News World & Report rankings and the National Research Council rankings) only report information about departments as a whole, rather than about their strengths in particular areas, such as conflict, violence, and peace studies in particular. This is also typically true of program reports published in other blogs, bulletin boards, and online fora. One result of this is that graduate students might have insufficient information to make a crucial career choice, potentially causing them to attend a program that is not a good fit for their interests. What is clearly needed then is a comprehensive guide to political conflict/violence and peace programs. For the third straight year, the Conflict Consortium has created such a guide for US political science PhD programs. The Conflict Consortium’s general goal is to provide scholars of conflict, peace and violence (broadly conceived) with information about conducting research and opportunities for scholarly engagement.

This review is based on a large survey that we conduced of scholars in research-oriented political science departments (the exploration of other departments is in the works). Specifically, we sent the survey to all 3,413 faculty members at the 120 institutions listed in the 2018 edition of US News World & Report’s Best Political Science Programs ranking. During the week we collected the data, 60 participants across 43 institutions completed the survey. Our hope is that more conflict/peace scholars will participate in future years.

We report the lightly cleaned results of our survey on the Conflict Consortium website. We also provide this data in a raw text file and in wide- and long-form datasets for grad students to more deeply examine. Our hope is that this information can help prospective conflict graduate students make better informed decisions about where to conduct their studies.

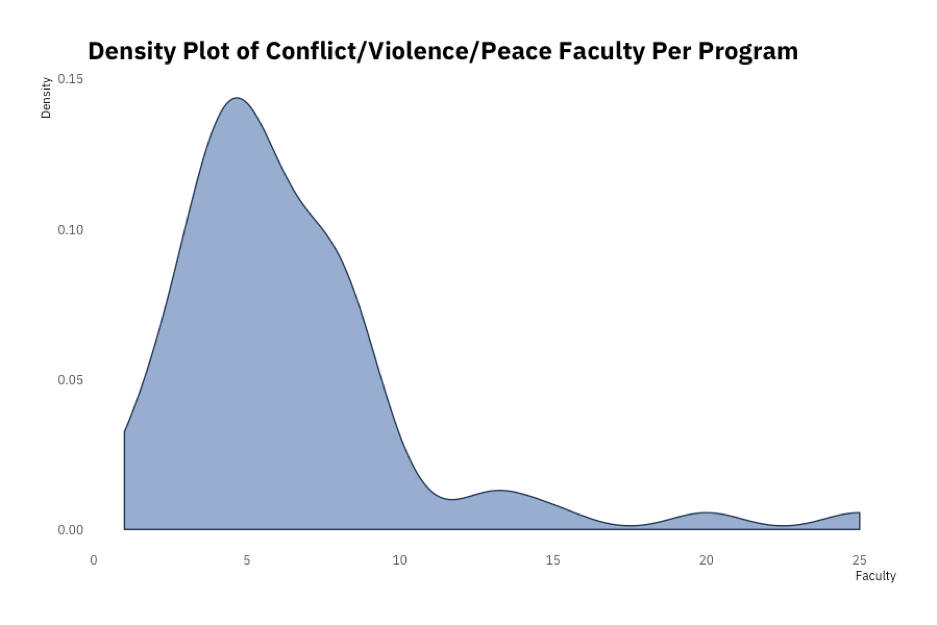

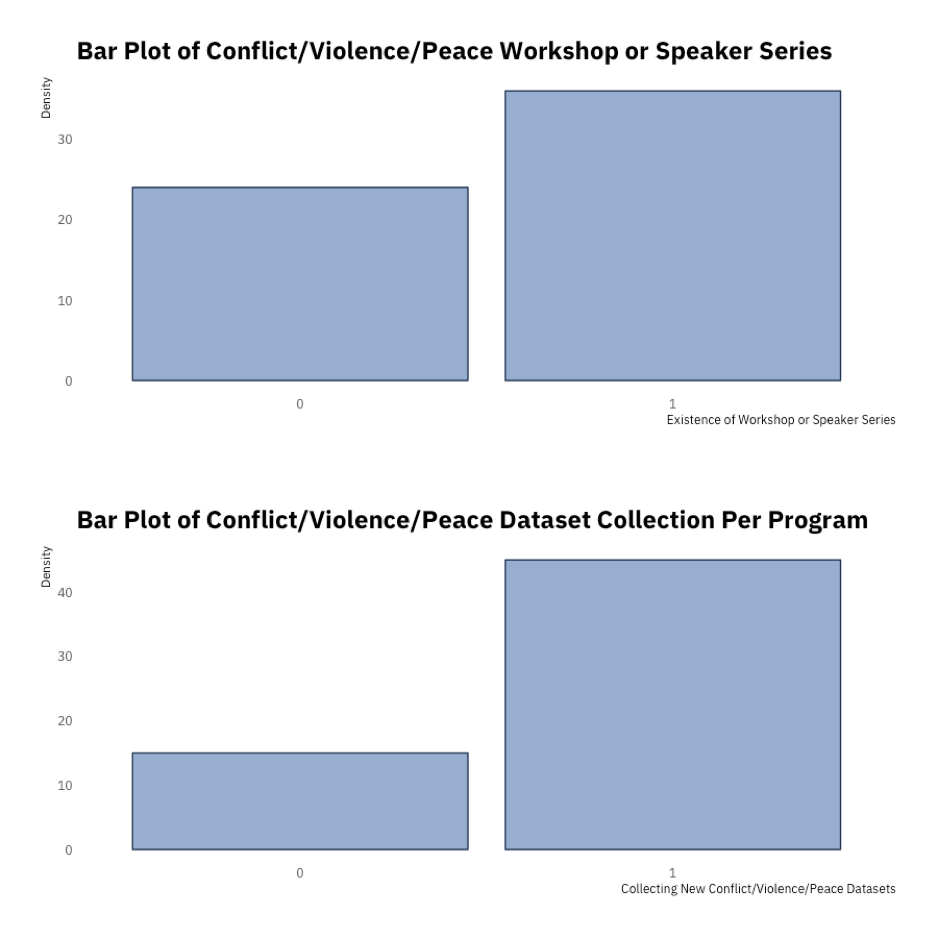

The survey results indicate that the field is thriving. Respondents from 43 different programs self-identified as conflict/peace scholars. Figure 1 reveals that there are places with a few scholars and other places with a dozen or even more; on average we find that a program has 6 in them. Figure 2 shows that these programs are places of considerable scholarly activity. Sixty percent of the programs host conflict/peace workshops or speaker series, and seventy-percent have faculty who are involved in actively collecting new conflict/peace datasets.

Figure 1

Figure 2

In addition to this information, our data also include the US News World and Report program ranking, as well as information about things like how many people study state repression, civil war or sexual violence at the global or sub-national levels.

These data could also potentially be combined to create different rankings of conflict/peace programs. To illustrate this, we create an index of program productivity and scholarly breadth. We include in this index measures of the number of conflict/peace faculty (scaled between 0 and 1), the number of different datasets being developed by faculty (scaled between 0 and 1), the number of different topics studied within the program (scaled between 0 and 1), and whether the program has a conflict/peace workshop or speaker series. We add these measures to create a continuous variable that ranges from 0-4, which we use to rank programs.

One might think that different variables should be included, or that they should be combined in different ways. Our goal here is not to create the definitive measure of this latent construct. The point is to show how the data we’re collecting can be used to transparently create measures related to conflict/peace programs, with the hope that others might do the same.

New Directions

While our primary interest in conducting this survey was to compile information for prospective graduate students, we also took the opportunity to ask respondents about the what they thought were the most theoretically and empirically underdeveloped topics in conflict and peace studies. Interestingly, respondents identified many more areas in need of theoretical development than empirical development, suggesting that researchers, including the prospective graduate students who might use our guide, should focus their effects on developing stories that explain conflict and peace outcomes, processes, and actions. A second important finding from these responses is that terrorism was identified as the topic most in need of theoretical and empirical development.

We also asked researchers about what they thought were the largest barriers to conflict and peace studies today. The majority of respondents listed issues related to data access and quality. Two respondents put it succinctly, responding with `Access to quality data’ and `Data limitations’. Others were more detailed, and high-lighted issues related to data sharing among researchers, the absence of data dealing with political elites, and the sparse resources available to conduct data-generating fieldwork.

The information we collected this year was more comprehensive than our first two surveys, but we hope that even more conflict/peace scholars will participate in future years. The success of this survey depends in part on the participation of individuals in the political conflict/violence and peace community. We would be very grateful if other scholars took a few minutes to complete the survey, which you can access here. We will update the guide and report back accordingly.

Thanks.

The Conflict Consortium

1 comment

It would be nice if anyone in the field could fill out the survey to contribute to the rankings. The first question asks which university you are a member of and if you are not a member of one of those on the list then you can’t advance. This excludes international scholars and those like me who teach at liberal arts colleges. It is easy to build in a skip in qualtrics so that we could still fill out the rest of the survey on our views of other institutions.