Guest post by Matthew Hauenstein and Madhav Joshi.

Two weeks ago, the US envoy to Afghanistan announced that American and Taliban negotiators had drafted a negotiation framework to end the 17-year long war in Afghanistan. Though American troops ousted the Taliban government following September 11th, the Taliban initiated a long-running insurgency against the US-backed Afghan government. After more than a decade of fighting, the Afghan government, the United States, and Taliban insurgents each failed to secure victory and, instead, the conflict has reached an unfavorable equilibrium for each of the parties. The framework deal, therefore, is expected to shift the status quo in Afghanistan’s politics and provide an exit strategy for US troops.

There are two potential obstacles in the negotiations. First, the Taliban have refused to meet with the Afghan government. Proxy negotiations are uncommon but can be successful. For example, in Macedonia, the government negotiated with representatives of the Albanian minority before the Ohrid Agreement. While the primary insurgent group was excluded, the political representatives were seen as proxies for the rebels. In Burundi, the main rebel group was excluded from the 2000 Arusha Accords but signed an agreement in 2003.

The American negotiators made a full agreement conditional on talks between the Afghan government and the Taliban. However, it is unclear whether the Taliban will accept this requirement. The New York Times reported that an anonymous Taliban official told the paper “he did not see the agreement as being dependent on… direct talks between the Taliban and the Afghan government.”

Second, the withdraw of American forces will be contentious. On the one hand, President Trump has made clear his preference for a smaller US military presence. In December, he announced the US would withdraw about half of the 14,000 personnel in Afghanistan. American negotiators offered to completely withdraw US forces if the Taliban agree to a ceasefire, negotiations with the Afghan government and to prevent terrorist groups from using Afghanistan as a base.

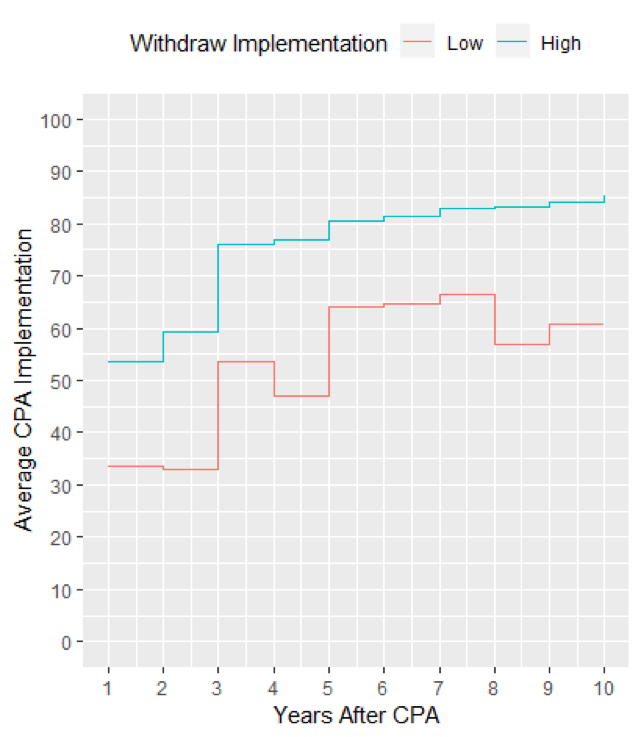

However, both the US and Afghan governments fear the Taliban will return to war after US forces leave. For comparison, we identified twelve Comprehensive Peace Agreements (CPAs) that included foreign troop withdrawals. Among those cases, withdrawals improved peace quality. When foreign troops leave, agreements are 77 percent implemented (on average), compared to 47 percent when they stay.

Still, American policymakers may see parallels to the collapse of South Vietnam or the civil war that followed the Soviet exit from Afghanistan. However, our data suggest that American withdrawal might not doom a settlement. The 1991 Paris Peace Accords succeeded in Cambodia, despite the withdrawal of the Vietnamese forces that installed and supported the government. Similarly, the 1995 Dayton Accords experienced high implementation, despite NATO’s transition from pre-agreement military operations to peacekeeping operations.

A major concern noted by both scholars and pundits is the fact that the current framework lacks a way to prevent the resumption of conflict after American troops withdraw. However, it is important to distinguish between a comprehensive agreement and a framework agreement. The former resolves the core dispute and often contains provisions for outside verification or enforcement. The latter simply sets out the conditions under which the former will be negotiated. The current agreement is even more preliminary: it is a draft framework agreement that has yet to be agreed to. Just because certain provisions are not being discussed does not mean they are off the table.

If the framework is agreed to, expect a series of lengthy negotiations that could result in multiple partial agreements before a comprehensive settlement. For example, the 2016 agreement between the FARC and Colombian government started with a similar peace process agreement. The parties then signed another six agreements before negotiating the final agreement. Similarly, in the Bangsamoro conflict in the Philippines, the first partial agreement was signed in 1997. The final settlement was not signed until 2014.

Not all peace processes result in a comprehensive agreement. Failure is still possible. However, our research shows that when negotiations fail they improve the likelihood of success in the future. As a result, there are few downsides to negotiations. Policymakers and scholars are right to worry about the viability of peace after the U.S. leaves. But, political science research suggests that—while negotiations are difficult and often protracted—they hold the potential for delivering peace in Afghanistan.

Matthew Hauenstein is a postdoctoral research associate at the Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies in the Keough School of Global Affairs at the University of Notre Dame. Madhav Joshi is an associate research professor and associate director of the Peace Accords Matrix at the Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies in the Keough School of Global Affairs at the University of Notre Dame.