Guest post by Margherita Belgioioso, Stefano Costalli, and Kristian Skrede Gleditsch.

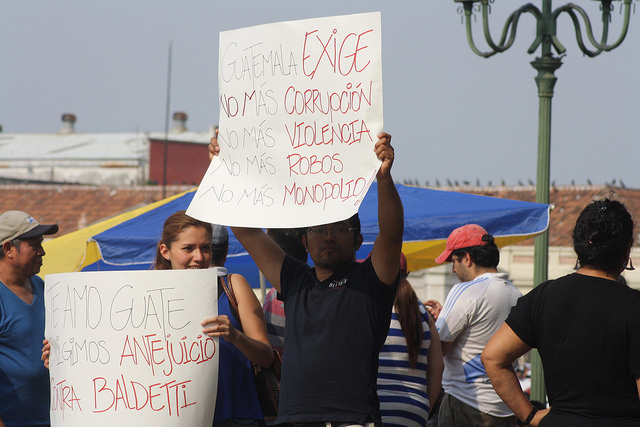

Recent research shows that nonviolent dissent can be more effective than armed violence and often presents many strategic advantages. Nonviolent campaigns are conceptually distinct from violent campaigns: however, mass nonviolent dissent campaigns often see break-away fringe groups engaging in terrorist campaigns. In a forthcoming article in Terrorism and Political Violence, we examine the impact of fringe terrorism on likely outcomes of non-violent campaigns. Fringe terrorism presents a credible challenge to nonviolent campaigns—although terrorist groups rarely manage to bring about large-scale armed uprisings or revolutions, they pose a risk of radicalization and violent escalation.

Violent fringe groups embedded within the broader context of nonviolent mass mobilization often see themselves as a revolutionary vanguard, resorting to terrorist attacks to provoke the state into confrontation in order to elicit broader support for armed struggle. For example, the Red Brigades, a violent flank of the New Leftist movement in Italy, expressed the logic of terrorist attacks as a strategy to attract greater support in their 1978 strategic manifesto:

“In this phase, the struggle must assume, by the initiative of the revolutionary vanguards, the form of war. …we …want war! …revolutionary violence pushes the enemy to face it, … it forces the enemy to react, to operate on the terrain of war: we intend to mobilize and to flush out the imperialist counterrevolution from the folds of the ‘democratic’ society where it has comfortably hidden in better times!”

Many violent groups have succeeded in discrediting nonviolent movements and driving away supporters from the moderate factions in nonviolent movements. Governments and moderate leadership of nonviolent campaigns generally hold opposing interests on the main issues in a conflict; however, they often have some degree of shared interest in avoiding escalating violence. On one hand, moderate organizations in nonviolent campaigns do not want to risk losing credibility and supporters as a consequence of terrorist outbidding. Similarly, governments are unlikely to accommodate factions that turn to terrorism, but may be willing to offer concessions to nonviolent movements. In short, moderate nonviolent dissent does not directly threaten the personal security of officials on the government side and leaves more space for negotiations, compromise, and possible future political influence for regime supporters.

Governments also know that simply offering token concessions to moderate organizations does not necessarily guarantee decreased support for groups engaging in terrorist violence. On the contrary, granting concessions could encourage more extremist violence. Concessions to nonviolent campaigns become more appealing when a government also believes that the leadership structure of a mass civil resistance campaign will have sufficient capacity to prevent increasing support for violent groups and the escalation of conflict after concessions. We argue that this is more likely when mass civil resistance campaigns have a hierarchical organizational structure and thus better prospects for preventing growth in support for fringe terrorist groups. We find that moderate groups with a stronger structure are more likely to see concessions in situations with fringe terrorism.

Take, for example, the events leading to the end of Communist rule in Albania in 1990-91. During the second half of 1990, mass civil resistance demonstrations emerged across Albania, fuelled by economic deprivation and decreasing fear of repression after the fall of the Berlin wall. Only a few months after the beginning of the protests, Albanian president Ramiz Alia found himself confronted by both a large-scale mass civil resistance campaign and a series of terrorist attacks against police forces and public governmental buildings.

In response to the escalating violence, the nonviolent opposition to Alia formed an umbrella organization called the Democratic Party of Albania. This group possessed a centralized, hierarchical structure, and immediately demonstrated its ability to maintain non-violent discipline and avoid further escalation of violence. The leader, Arben Imami, denounced episodes of violence and stressed the Democratic Party’s desire for continuing peaceful dialogue with Communist leaders. Alia subsequently met with Democratic Party leaders and initiated a process of concessions, including the sacking of five politburo members and a promise to hold multi-party elections the following February. Over the subsequent months, the communist party joined the opposition parties in a coalition government to secure political stability and isolate violent fringes. Alia eventually decided to step down because the violence was quickly escalating and threatened political stability in the country.

Fringe terrorism is a clear risk to non-violent dissident campaigns and often undermines ongoing campaigns, either through outbidding or scaring away potential supports. But the example of Albania shows that better organized movements are more resilient to fringe violence, and they are often able to convert potential challenges into opportunities.

Margherita Belgioioso is Assistant Professor of International Relations and International Security at Brunel University London. Stefano Costalli is Assistant Professor of Political Science in the Department of Political and Social Sciences at the University of Florence, Italy. Kristian Skrede Gleditsch is Regius Professor of Political Science at the University of Essex and a research associate at the Peace Research Institute Oslo (PRIO).