Guest post by Kelsey Norman

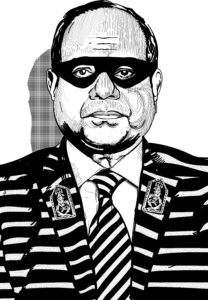

Egypt has arguably seen the most heavy handed retrenchment of authoritarianism in the Middle East and North Africa since the 2011 revolution failed to usher in a democratic transformation. Since rising to prominence in 2013, and solidifying his rule through elections in 2014, Egyptian President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi has proven to be more repressive in his crackdown on opponents—Islamists, activists, opposition figures, and anyone else he deems a threat—than former President Hosni Mubarak. Fearing popular mobilization, the government passed a law in 2013 that banned public protest.

And yet on September 20, 2019, Egyptians took to the streets in isolated—but substantial—protests across the country in cities including Cairo, Suez, Damietta and Alexandria. Those who dared to participate, in the face of almost certain repercussions from authorities, were responding to a set of videos released in the preceding weeks by a wealthy contractor-cum–actor, Mohammed Ali. Broadcasting via YouTube from self-imposed exile in Spain, Ali told fellow Egyptians—60 percent of whom are either “poor” or “vulnerable”—about the corruption and graft he witnessed and participated in while working with the Sisi government. Claiming he is owed millions, Ali presented a slew of dates, financial figures, and names of individuals in the military involved in the schemes. This specificity helped him connect with viewers who were likely aware that corruption was occurring, but might not have had a tangible sense of what form it was taking, and the extent of it.

While the government’s initial reaction was to claim that protests were small or simply did not occur, the response by security forces was immense. Anyone who dared protest risked indefinite detention, and the Egyptian Commission for Rights and Freedoms reported that 166 individuals were arrested on September 20th and 21st alone. As Mohammed Ali called for a second set of protests, police cordoned off the streets leading to Tahrir Square in central Cairo, and began conducting “spot-checks” of pedestrians’ phones, scanning their social media and YouTube history for any evidence of having watched Ali’s videos. Some individuals who happened to be passing through the square or entering the metro station beneath it were also detained and moved between police stations and national security offices, with friends and family unable to locate them.

The government also targeted well-known Egyptian activists, including Alaa Abd El Fattah, who was imprisoned in 2013, and was only recently released on parole. Abd El Fattah’s family issued a statement after visiting him in prison, documenting an exchange with an officer who told Abd El Fattah that prison is made to “teach people like [him] a lesson” and that he “will be in prison for the rest of his life.” Alaa Abd El Fattah’s lawyer was also arrested, as were other human rights lawyers who attempted to defend those who were detained, including Mahienour el-Masry and Esraa Abdelfattah. In total, there were more than 4,000 arrests in four weeks.

The immense and ongoing crackdown since September is evidence of a state concerned for its own survival. Disbelieving that a former government contractor could be so influential, the state lashed out at any private or public indication of dissent and targeted well-known activists in order to send a message to those who might consider defying its authority. While Ali claims to be acting alone, the state asserts that he is supported by the Muslim Brotherhood (their usual scapegoat). Still others are suggesting the possibility of internal dissent, and even a “soft coup,” wherein elements of the military hope to cultivate external popular support for an internally led leadership transition. One theory asserts, for example, that the general intelligence service (el mukhabarat) is attempting to reclaim power from the military intelligence (idarat el mukhabarat el harbiya wel istitla), from whose ranks Sisi rose to prominence.

It remains unclear whether we are witnessing the beginning of an end, or a retrenchment of control within Sisi’s authoritarian regime. Egyptians—both within Egypt and those in exile abroad—are skeptical of Mohammed Ali’s intentions, uncertain about possible dissention underway within the military regime, and weary of what would come next if Sisi were removed from power. Regardless, the sudden wave of protests in Egypt demonstrate that those who participated in the 2011 uprising—as well as a new wave of youthful activists—have not been entirely deterred by the repressive measures of the last eight years. What is more, these protests come after a summer that saw protests unseat governments in Algeria and Sudan, and amidst mobilization that has erupted in recent weeks in Iraq and Lebanon. While commentators and policymakers have branded the so-called Arab Spring a failure and proclaimed the onset of “winter,” recent events show that activists and those seeking reform, freedom, and social justice are willing to play the long game.

Dr. Kelsey Norman is a Fellow for the Middle East at the Baker Institute for Public Policy at Rice University, where her research focuses on women’s rights, human rights, refugees in the Middle East and North Africa.