By guest contributor Divya Ramjee

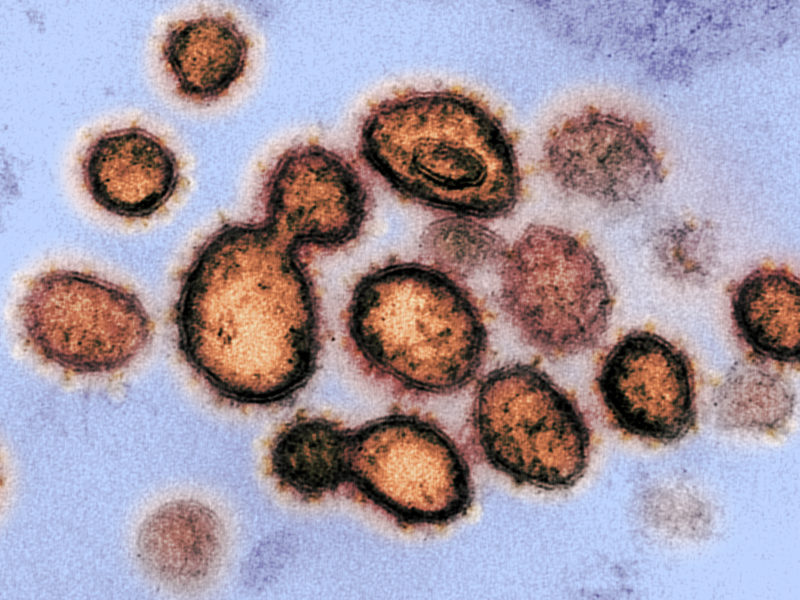

We are fighting an “invisible enemy.” The phrase has been frequently used to describe global efforts to rein in the spread of SARS-CoV-2, better known by the disease it causes—COVID-19. The current pandemic has caused unparalleled levels of fear and panic across the world and, in some countries, has resulted in faulty and myopic policies.

All pathogenic viruses are invisible enemies; they infect and spread surreptitiously, causing damage before symptoms make them known—hence the use of the word “virus” for malicious computer programs, which act similarly. As with pathogenic threats like SARS-CoV-2, the scope and scale of cyber threats are pandemic as well. Cyber threats, better specified as cybercrime, affect society on a global scale, oftentimes with the points of origin halfway across the world, and cause trillions of dollars in losses. Today, cybercrime is perpetrated by different types of malware, including computer viruses and other malicious software (e.g., ransomware, spyware, etc.), and social engineering techniques (e.g., phishing, fraud, etc.).

Both of these types of threats behave similarly and deserve similar considerations when constructing policies for preparedness and response. In the World Economic Forum’s Global Risks Report 2020, emerging infectious diseases and cybercrime are listed as top threats—with a high likelihood of occurrence and potential for long-term national and global instability. Both are infrequent but potentially devastating. Both should be approached as ongoing threats.

The COVID-19 pandemic has jeopardized the stability and security of countries across the world. The United States has attempted to adopt a war-like response to contend with failures of preparedness, but at present has fallen short. Despite warnings from researchers about a pandemic threat and the Global Health Security Index 2019 report’s warning that no country was adequately prepared to handle a pandemic—the US neglected to make the nation adequately ready.

Perhaps the most critical realization for the United States, and for all countries worldwide, is that COVID-19 is merely the most recent example of the complex and continuing threats of emerging infectious diseases. The threat of emerging pathogens is foremost a public health problem, one that existed long before this pandemic and one that will continue to exist well after. Similarly with cyber threats, while there are instances of national-level events, the threat of cybercrimes—foremost a criminal problem—continues to remain prevalent before and after every high-level cyber event.

Trying to institute protections against something that can neither be seen nor properly quantified fuels anxiety among the public and policymakers. Our lack of expertise with such abstract threats, and the fear-inducing emotional priming of worst-case scenarios, makes us view large-scale yet infrequent events as “doom”-like threats. We have a low tolerance for uncertainty and anxiety when it comes to understanding risk, and, in a paradoxical way, find comfort in the structure of expecting a catastrophic but rare event rather than considering the fluid spectrum of risks that are more likely.

Complicating matters is a combination of policymakers neglecting to proactively develop preparedness measures and a public that often fails to perceive a threat as significant. Policymakers are rarely held accountable for their lack of preparedness and rather are graded more harshly by the public on the success or failure of their response. The reward of increased public support from backing response relief outweighs the risk of losses from lack of preparedness. However, this continued focus on reactive processes inevitably leads to harsher defensive measures and more extensive damage. This is the case with COVID-19 and the failure of leadership to act in January and is also true of major data breaches and the significant delays before threat mitigation and victim notification occur.

There are two critical elements to consider when developing preparedness policies for these invisible global threats. The first is tracking, testing, and tracing. We must improve our abilities to track emerging threats, strategically test for their presence, and trace their exposure. Accurately understanding invisible threats relies on having enough comprehensive data. With COVID-19 in the US, there was a six-week lag before widespread testing and tracing of SARS-CoV-2 infections were federally implemented. This lag allowed the virus to spread both domestically and internationally and added an additional risk of the virus becoming endemic. Unfortunately, testing is still not implemented at a sufficient scale for the nation to properly gauge the scope of the threat; we will most likely only have partial data after this wave of the pandemic. Even so, it is critical the United States, and all countries, invest in developing newer computational models and machine learning algorithms for tracking future invisible threats with any data available. The second, and equally crucial, element is increased and consistent investment. Invisible threats will continue, and mitigating the risks they pose requires increased funding and routine support for preparedness research, development, and implementation.

Across the globe, criminals will continue to find ways to take advantage of anxiety and uncertainty during times of emergency and disaster. Agencies including the US Department of Homeland Security, the Federal Bureau of Investigation, Europol, Interpol, and the World Health Organization have issued warnings to remain alert for COVID-19-related scams, malware, phishing campaigns, and counterfeit personal protective equipment (PPE), among others. Concern about contracting SARS-CoV-2 tends to eclipse concern of being defrauded, making us all more susceptible to falling victim to cybercrime. We need to remain vigilant to the pandemic threat of COVID-19 as well as the global threat of cybercrime, and in both situations, practice good hygiene.

Divya Ramjee is doctoral student at American University. Her background includes prior work in infectious disease research, federal pandemic policy, cybercrime, and intellectual property crime.

1 comment

A further complication in combating cybercrime is that securing the Internet against criminals means closing weaknesses that governments use for various state security functions of dubious legality and even weaker legitimacy.

There is a binary choice between an Internet that’s safe for the public and an Internet that’s open for mass surveillance and offensive cyberattacks against adversaries. Governments have repeatedly chosen to prioritize the latter over the former and the epidemic of cybercrime is the result.

Technologically hardening the Internet against cybercrime is not possible as long as most technology companies are subject to the whims of the US government and the US security establishment continues to feel entitled to low-cost mass surveillance and cyberattack capabilities.