Guest post by Travis Curtice

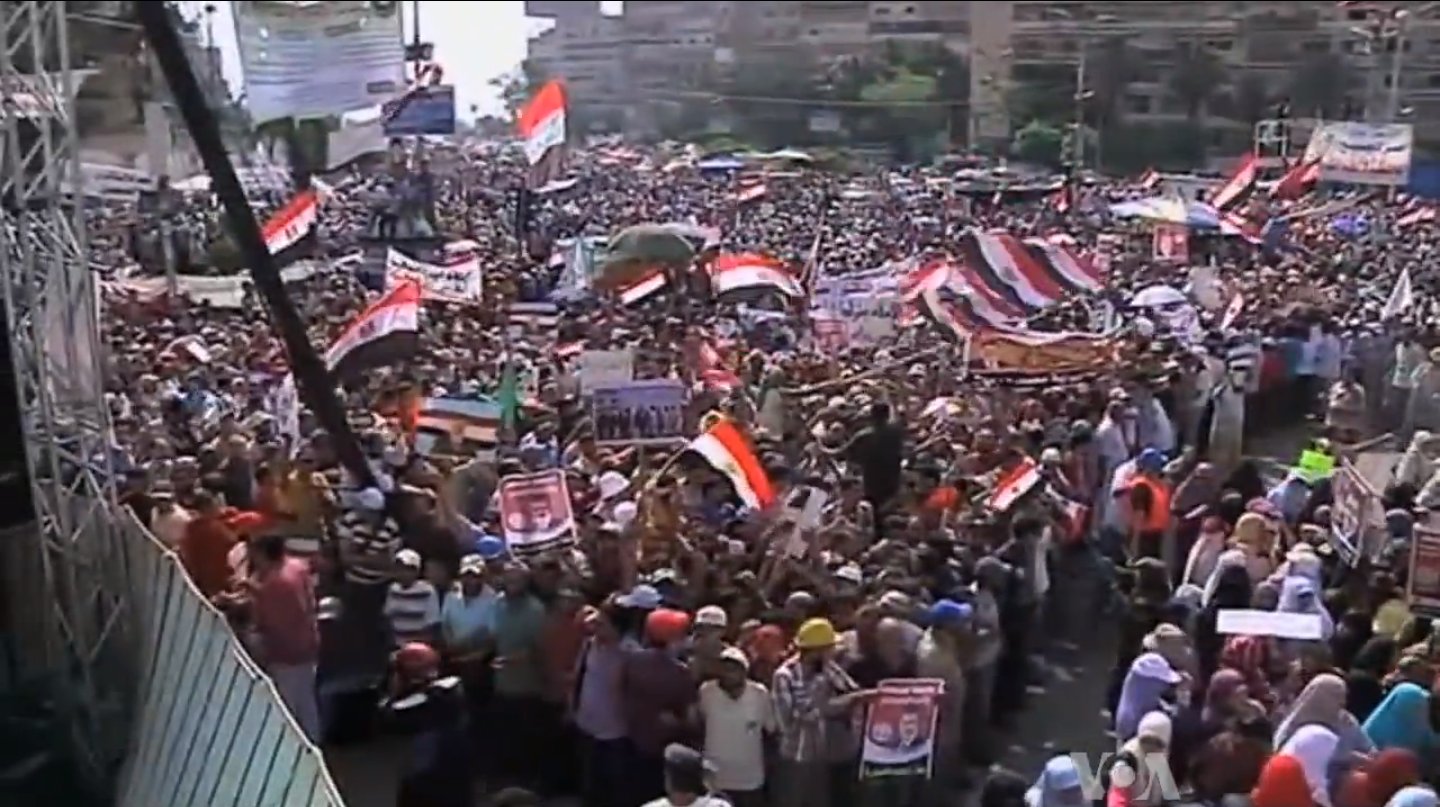

In the United States, thousands of protestors continue to take to the streets to protest the murder of George Floyd by a Minneapolis police officer. Floyd’s murder occurred about two months after Breonna Taylor was killed in her home by Louisville Metro Police Department officers. These extrajudicial murders are but the latest tragic reflection of an unjust criminal justice system that employs “coercion, containment, repression, surveillance, regulation, predation, discipline, and violence” as mechanisms of control—disproportionally meted out against Black and Indigenous communities.

Police in the United States are highly fragmented, both across and within states. However, the protests have been national in response, with demonstrations in all 50 states. Others from around the world have joined to stand in solidarity with the Black Lives Matter movement and against police brutality.

Although some police officers, commissioners, and policymakers have marched in solidarity with protesters, the overwhelming response by the police in the United States has been to use repressive tactics to quell the protests. Police abuse has included targeting journalists with over 300 (and counting) violations of press freedom; arbitrary enforcement of curfews; and a countless number of physical integrity violations, culminating in over 9,000 protestors being arrested.

What effect will this have on protesters? The relationship between repression and dissent has been long examined by scholars, but we know less about how repression—illegitimate actions taken by the police—shapes people’s attitudes toward the police and their willingness to engage in future protests.

But evidence from other countries may provide some clues.

Political authorities relying on police to repress dissent is anything but new. The Ugandan government has used violence to deter political challengers since Yoweri Museveni became president in 1986. But when the police employ teargas and live fire to clear crowds, beating and arbitrarily arresting protesters, they tear away at their own legitimacy and support. Our study looking at the policing of protests in Uganda shows that when police officers are seen as excessively violent, it results in political backlash across the population, increasing dissent and decreasing support for the police.

Ostensibly, the goal of police repression is to halt protest and discourage it from happening in the future. But we find no evidence that observing excessive police violence reduced participants’ willingness to criticize or protest the government. Instead, hearing about excessive police force—even when it was only hypothetical—decreased people’s support for the police. Even Ugandans who support the ruling party were more likely to say they’d publicly criticize and protest police action after hearing about excessive force than those who heard about appropriate police action.

Adrienne LeBas and Lauren Young have studied the same dynamics in Zimbabwe. They, too, find that exposure to both repression and protest increases citizens’ willingness to engage in protest and other acts of dissent. In their study of protests in Russia, Timothy Frye and Ekaterina Borisova show that autocrats can increase trust in government by allowing protest when it is unexpected. So, although protests can improve confidence in the state, police abuse of protestors actually decreases it.

The evidence, in other words, suggests that repression is not as effective a tool in discouraging protest as is generally assumed. Uganda’s security forces’ recent crackdown on dissent resulted in even more protests and collective action across the country.

The recent wave of excessive policing of protests in the United States highlights an inherent tension. In many contexts, the police are designed to provide security, deterring crime. On the other hand, they are also coercive agents of the state used by political authorities to repress dissent and maintain control.

Police differ from other security forces, like the military, because they rely on civilians’ cooperation in order to be effective at their daily tasks. In order to provide security and deter crimes, police require the support of the public; they gain that support by building trust in the way they interact with those they are policing. When people think the police are fair and effective, they are more likely to cooperate with them to promote public safety.

Repressive action by the police, whether that involves violently shutting down peaceful protests, suppressing journalists, or implementing racially motivated stop-and-frisks, divides many citizens from their government. These acts undermine the relationship between the police and those who have been targeted, encouraging greater dissent.

In democracies—where power explicitly lies with the people, and where politicians face the possibility of electoral sanction—police abuse ought to create a political backlash. Protests might continue, shaping how voters mobilize against political authorities responsible for the abuse. But even in democracies, this is being tested. Governments of all kinds may be tempted to use force to quell opposition and maintain the political status quo, but they should know that doing so increases public criticism and provides the kindling for future protests.

This is an opportunity to reimagine the relationship between individuals and the police. But doing so requires listening to those who have experienced the police as repressive agents of the state. From police abolition to reform, scholars and advocates are already imagining what this might take.

Travis Curtice is a 2019-2020 Peace Scholar Fellow at the United States Institute of Peace, and a 2020-2021 Dickey Center Fellow in U.S. Foreign Policy and International Security at Dartmouth. His article with Brandon Behlendorf was recently accepted for publication in the Journal of Conflict Resolution.