By Fiorella Vera-Adrianzén, Peter Dixon, Daniel Ortega, Edwin Cubillos Rodríguez, Manuela Muñoz Ramírez, Rosario Arias Callejas, Saraya Bonilla Lozada, Oscar Vargas, Mariángela Villamil Cancino, Pamina Firchow

In Colombia, the COVID-19 pandemic and national State of Emergency have weakened an already fragile peace process. Armed groups have increased militarization and territorial control, often playing the role of authorities enforcing social isolation. Institutions of the peace process have temporarily suspended activities. The pandemic has reactivated and uncovered multiple dynamics of the conflict and slowed implementation of the 2016 Peace Accord, particularly in regions considered key to its success.

But peace in Colombia is not a total loss under COVID-19. In fact, while posing fundamental challenges, the pandemic has also highlighted where the Colombian state must make key local investments to consolidate the very real gains that communities once ravaged by war have made over the last decade. Specifically, the state must invest in the local institutions that communities rely on to build and sustain peace, whose significance often remains hidden under more normal circumstances.

To see why, take the municipality of Dabeiba. Dabeiba is known as the gateway to Urabá—a strategic corridor that was hit hard by the armed conflict and is now a key site for Colombia’s most important peace and victims’ institutions. Last December, the country’s new restorative justice court, the Special Jurisdiction for Peace, found a mass grave in Dabeiba with multiple victims of extrajudicial killings—an important step toward dealing with the past for the residents of Dabeiba, four-fifths of whom identify as victims of the armed conflict.

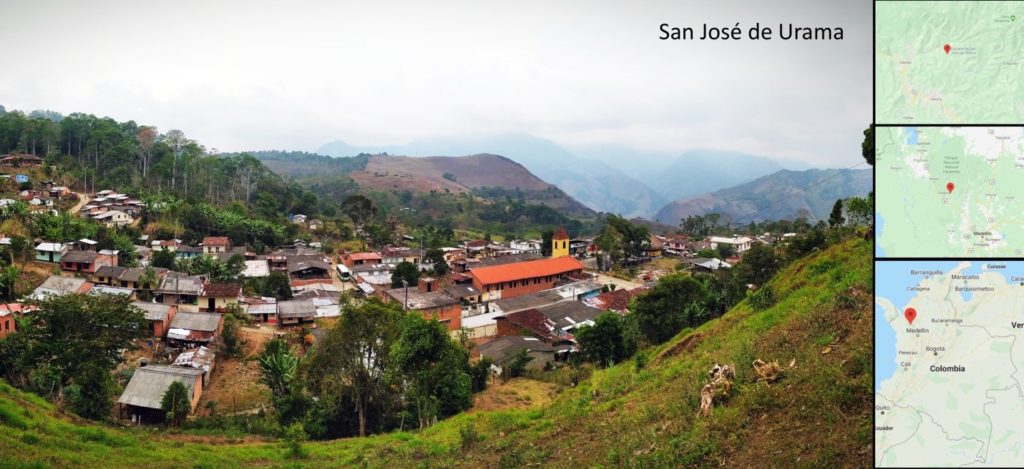

Under COVID-19, Dabeiba has suffered the same violence and economic devastation as the rest of rural Colombia. But one community stands out, both for its progress before the pandemic, and for its resilience during quarantine: San José de Urama. Following the 2006 paramilitary demobilization and 2016 Peace Agreement with the FARC, Urama was reborn. In the face of entrenched paramilitary presence, its population increased, new homes were built, and a small police outpost was established. In turn, its economy and social life were revitalized.

For the last year, our team has assessed how the peace process is fairing in communities like Urama by asking people about their everyday experiences and understandings of coexistence and justice. Compared to neighboring communities, people in Urama are more positive about how their town has fared. Our research suggests that several things are fueling these perceptions. These include increased economic activity, with people coming from afar to shop and sell at Urama’s market; organized efforts to learn what happened to loved ones who were murdered during the conflict; improved understanding of the history of the armed conflict; and improved security from the police presence, among others.

These indicators tell a range of stories. During the pandemic, we have seen that Urama has benefitted from local institutions that its neighbors lack, which have imbued residents with optimism about their economy and security and helped them manage daily life, especially under quarantine. COVID-19 has made the contributions of these local institutions to peace all the more visible.

For example, none of the other communities where we collected data have a police outpost. Before the pandemic, the police in Urama were beginning to create a unique sense of security, both for residents and visitors, which we have not seen elsewhere. Under quarantine, the police brokered the town’s relationship with the local neo-paramilitary group, Autodefensas Gaitanistas de Colombia, which had imposed its own quarantine order soon after the official one. The police also helped negotiate agreements for safe behavior with the local church, retailers, and food providers, and approved economic and cultural activities that respect social isolation rules.

To some extent, Urama has also been able to preserve its status as an economic center for villages in the surrounding hills. Under COVID-19, market activity slowed, but some movement began to resume in line with local social distancing norms about two months into the quarantine, when chivas (local buses) returned to Urama’s center on a limited schedule.

Still, these are fragile conditions. With mounting insecurity, economic struggle, and stifled social life, Urama’s progress before the pandemic represents what Colombia stands to lose if it cannot consolidate communities’ local gains towards peace. Tellingly, trash—a potent symbol among Urama residents of the strength, or weakness, of the town’s social structures—is piling up again on the streets and hillsides, a worrying sign of the deterioration of local institutions under the pandemic.

COVID-19 has exposed and tested social structures that govern society in post-conflict Colombia, and in so doing, offers a strong indication of where resilience lies at the hyper-local level. Urama stands ready to deal with the past, with strong demands for truth and reparations, but they need the state’s support and accompaniment to do so. With the continued presence of non-state armed groups in and around communities in recovery like Urama, the local state plays a crucial role in promoting an official social order, which can help reinforce peaceful coexistence and a sense of justice. To strengthen peace processes in local communities, the state can—and must—nurture peacebuilding from the bottom-up.

The authors are a team of Brandeis University researchers based in the US and Colombia working with the Everyday Peace Indicators Project to study issues of coexistence and justice in mostly rural Colombia funded by the National Science Foundation, the United States Institute of Peace, The Inter-American Foundation, and Humanity United.