Guest post by Phillip Davis

The murder of Ahmaud Arbery, a 25-year-old Georgia resident, by two private citizens was a stark reminder of the problem of vigilantism. Though romanticized in US popular culture with heroes such as Batman and The Green Arrow, vigilantism is a response to governance failures and can lead to further violence.

Defined as “premeditated acts of force—or threatened force—by autonomous citizens,” vigilantism is a calculated, willful activity that takes place outside formal institutions, but is sometimes tacitly supported or perpetrated by institutional actors. Vigilantes are more prevalent in times of political and cultural transition, in areas with high levels of cultural diversity, and in times of institutional instability. And though vigilantes sometimes solve problems when states cannot, vigilantism is prone to opportunism and can generate violence, corruption, and social othering.

Vigilantes often operate in weak states that lack the capacity to provide security and services to citizens, and legitimacy among their populace. Take the case of Nigeria. In 2013, the Civilian Joint Task Force (CJTF) was created by citizens of the city Maiduguri to defend their community from Boko Haram and the government’s counterinsurgency operations. With knowledge of the local language and culture and ties in the community, CJTF was more trusted among locals than state security forces. CJTF was so successful that state officials provided them with resources and training so they could manage intelligence, surveillance, arrest, and patrol operations, even outside of Maiduguri.

There were downsides, however. Some CJTF members exploited their positions to engage in drug trafficking and other criminal activities, while other members insisted on “donations”—i.e., bribes—from community members. There were also cases of violence, including when vigilantes paraded 40 heads of alleged Boko Haram members on pikes.

Mexico provides another example. There, government inability to counter violence from drug trafficking organizations led vigilante groups to emerge in over 60 Mexican cities to control crime. Since 2014, these self-defense organizations have become heavily armed; some collaborate with local authorities, and some have helped to contain violence. But some groups also carry out violence themselves. In Michoacán, vigilante groups conducted citizen arrests of local police forces and firebombed city hall. Such violence limits the space for nonviolent civil action or negotiations. Additionally, as in Nigeria, some Mexican vigilantes have deviated from the original self-defense mission to collude with and join criminal gangs.

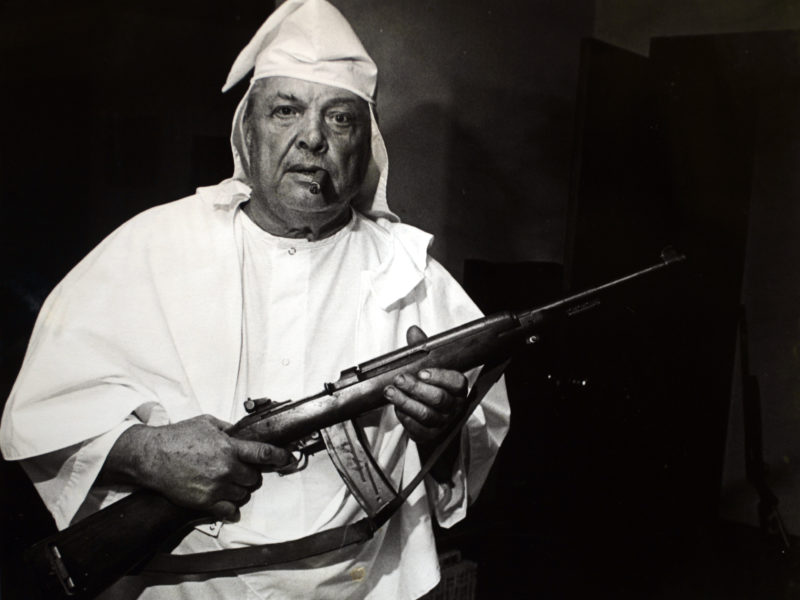

Weak states may seem an obvious home for vigilantes, but vigilantism can also emerge in strong states—especially in areas transforming culturally or institutionally. In the US, systemic racism has provided the impetus for vigilante groups for centuries. Beginning in the 17th century, patrollers made up of poor whites would, in the name of fighting crime, punish and kill Blacks in order to suppress potential slave rebellions. This continued after the Civil War eliminated slavery, with groups such as the Ku Klux Klan, acting at times with the tacit support of law enforcement, carrying out lynchings with impunity.

In 2020, we see both isolated incidents of vigilantism—such as in Seffner, Florida, where a Black teenager was illegally detained by a 54-year-old community member who falsely accused the teenager of breaking into cars and stealing a bike—and larger demonstrations, including the armed protests against pandemic lockdowns. The government’s lack of force in the latter cases contrasts sharply with its use of force against non-violent protests against police injustice supported by Black Lives Matter, and suggests some form of government complicity with right-wing militias.

A majority of militia groups—typically anti-government, right-wing, and motivated by conspiracies—view protests against police injustice and racism as illegitimate. To provide “crime control,” vigilante groups have threatened the use of violence to deter “rioting.” For example, in Omak, Washington, students organizing a protest against police injustice were confronted with messages characterizing the assembly as “target practice”. While 400 people protested, an armed militia stood guard on the ground and on rooftops awaiting any protestors who got “out of line.” These threats and use of violence by private citizens is supported by President Donald Trump, who has characterized vigilantes as “good people” while describing protestors, especially black protestors, as “thugs”.

Recently, a Black militia group named Not F***ing Around Coalition peacefully marched through Stone Mountain Park near Atlanta, GA arguing for the removal of a confederate statue. Time will tell whether more Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC) vigilante groups will emerge as the US confronts societal and governmental transition. But without explicit or implicit support from the government, BIPOC vigilante groups are unlikely to have the same impact as their white militia counterparts.

Political scientists agree that vigilantism often indicates aspects of government failure. In Nigeria and Mexico, vigilantism has appeared as the governments struggle with insurgency and cartel violence. Failures in governance can also appear in strong states, though, in the presence of societal changes. In America, systemic racism has led to myriad varieties of vigilantism. Though vigilante action can address governance failures, if prolonged, left unchecked, or rooted in a system that excludes and oppresses, it can cause more harm than good.

Phillip R. Davis II is an appointed Presidential Management Fellow and graduate student at the Josef Korbel School of International Studies – University of Denver studying International Security.

1 comment

Great article, Phillip. The intersection of weak governance, vigilantism, and corruption is space we need to pay attention to. The availability of (il/legal) weapons is also a huge component of this. Thanks for sharing.