Guest post by Christoph Steinert

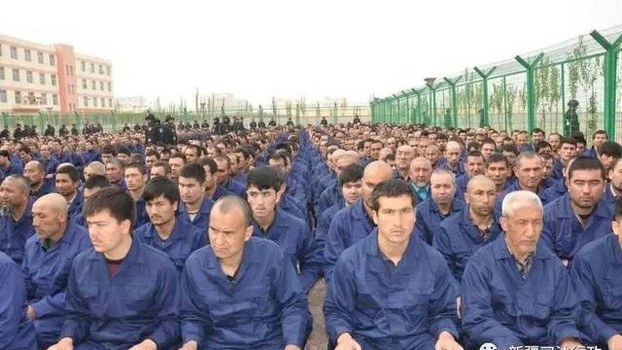

Since spring 2017, the Chinese province Xinjiang has been the site of an unprecedented forced re-education campaign resulting in the detention of up to 3 million people, especially Uyghur, Kazakh, and Kyrgyz minorities. While the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) euphemistically refers to the detention camps as “vocational education and training centers,” human rights organizations such as Human Rights Watch have accused the Chinese government of horrific human rights abuses. The detention system is extra-legal in nature, operating parallel to the regular prison and detention system. Inside the detention camps, detainees are forced to work, learn Mandarin Chinese, and praise the CCP while suffering physical and psychological abuse.

Despite CCP denials and systematic targeting of non-governmental organizations (NGOs) that seek to uncover the human rights abuses, robust evidence of the existence of the detention camps in Xinjiang exists. Among the key pieces of evidence are construction bids related to the facilities; leaked government documents such as the China Cables or the Karakax list; eyewitnesses reports; and satellite imagery.

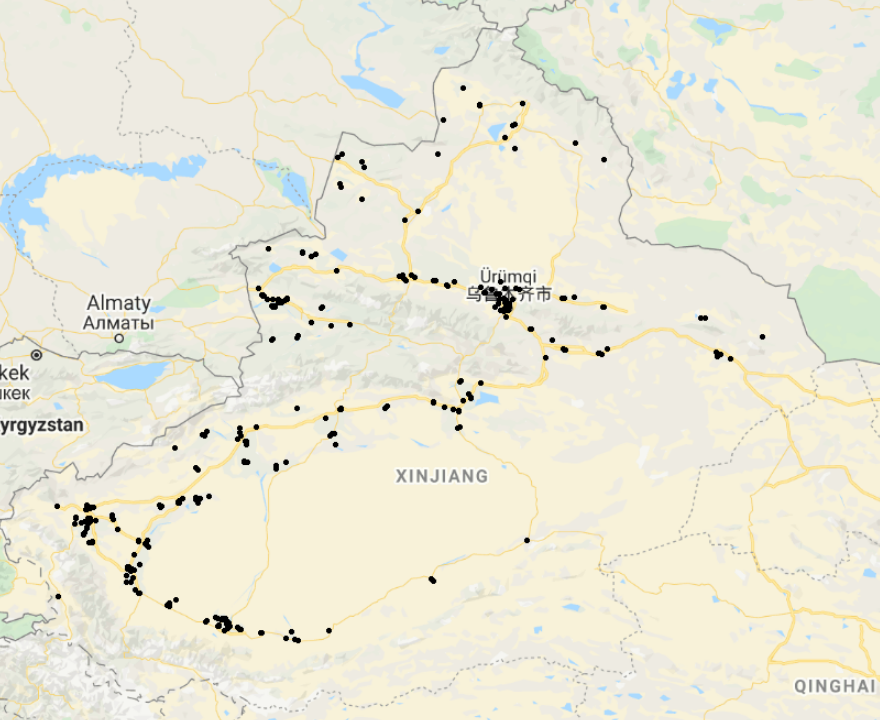

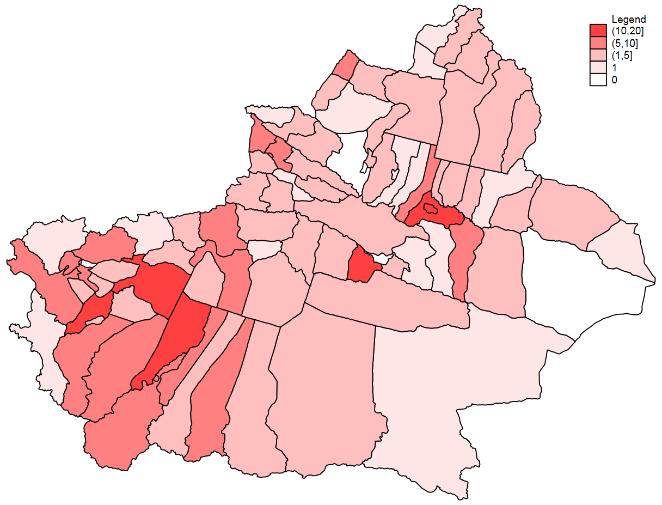

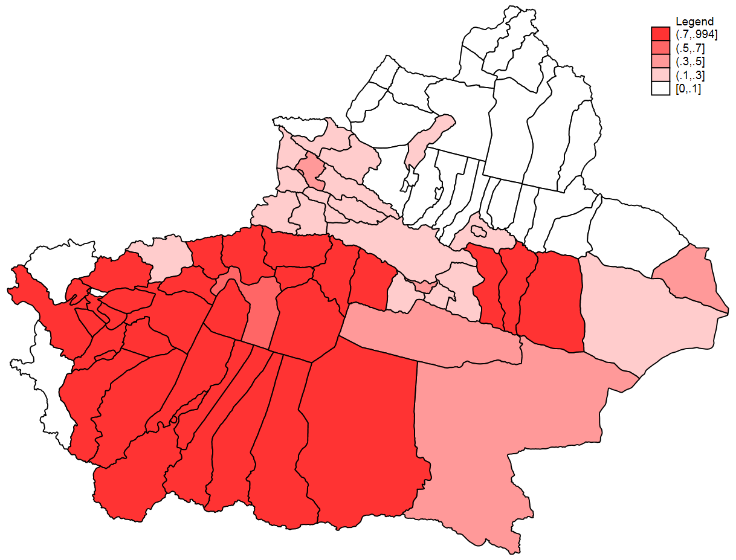

The most comprehensive satellite data of the detention camps is available at the Xinjiang Data Project, which contains the coordinates of 388 known detention facilities. Figure 1a presents a map of the detention facilities plotted to Google Maps satellite imagery. In Figure 1b, I aggregate the data by counties, demonstrating that most of the known detention camps are located in Xinjiang’s capital Ürümqi and in the south-western part of Xinjiang. Figure 2 shows that the share of ethnic Uyghurs per county is also highest in the south-western part of Xinjiang, suggesting they are particularly targeted.

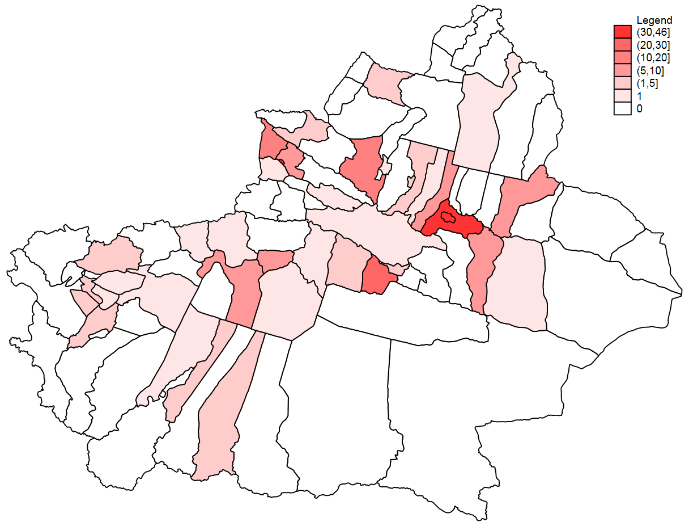

Human rights advocacy frequently relies on stories about individual victims. How much do we know about the identities of the political prisoners from Xinjiang? The names of all known political prisoners in China are stored in the Political Prisoner Database of the US Congressional-Executive Commission on China (CECC), which relies on open source information to collect demographic data of Chinese political prisoners. Figure 3a shows aggregated numbers of the political prisoners from Xinjiang who are registered in the Political Prisoner Database mapped by their presumed counties of detention. On average, only 2.2 political prisoners are known per detention camp (as of January 2021) representing a tiny subset of the true population of political prisoners.

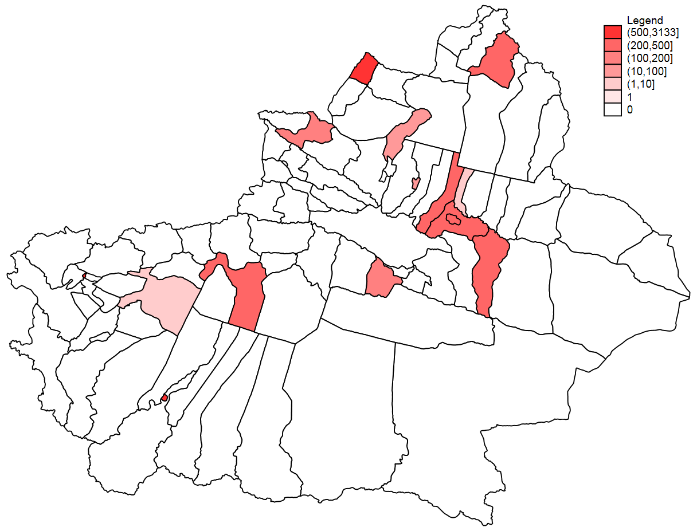

Our information differs significantly between counties. For instance, although the satellite data suggests there are nine detention camps are in Tacheng county, there are no political prisoners from Tacheng in the Political Prisoner Database. In contrast, 46 political prisoners from Ghulja City are registered in the Political Prisoner Database, where satellite data likewise suggests the existence of nine detention camps. Surprisingly, the Political Prisoner Database reports that political prisoners are detained in some counties (e.g., Wusu Shi, Yanqi) where we lack information on the existence of detention camps. Once again, the picture is different when we look at the prisoner data provided by the Xinjiang Victims Database as shown in Figure 3b, which draws primarily on testimonies of family members and acquaintances of detainees.

Obtaining information on political prisoners in autocracies is exceptionally difficult. Human rights data tend to reflect our (limited) reporting capacities rather than the actual number of human rights abuses. The under-reporting tends to follow a systematic pattern since information is especially difficult to obtain from certain locations, such as rural regions. Given the difficulty in obtaining data, the political prisoner data from Xinjiang should not be taken at face value. For researchers, the example also shows that generating highly disaggregated county-level data does not necessarily imply that human rights data is accurate in its aggregate.

The unknown identities of political prisoners in Xinjiang are not merely a statistical concern. It is a moral imperative to hold the Chinese government accountable for its massive human rights abuse in Xinjiang. Generating in-depth evidence about the detention camps may help spur policy changes, such as the recent US ban of cotton and tomatoes from Xinjiang. We need better information about both the political prisoners and the perpetrators of atrocities in Xinjiang to provide a foundation for future transitional justice and reparations. Human rights advocacy is most powerful when it is personalized—when the names and stories of the victims are known. Giving the victims a name will require investing more resources in the invaluable work of those organizations that uncover the political prisoners of Xinjiang.

Christoph Valentin Steinert is a PhD-student in the Graduate School for Economic and Social Science at the University of Mannheim. He published his research among others in the Journal of Peace Research, International Interactions, and Journal of Global Security Studies.