Guest post by Philip B.K. Potter, Chen Wang, and Claire Oto

The ability to control information has long been one of the most powerful tools at an autocrat’s disposal, but today’s institutionalized autocracies struggle to wield it in modern media environments. Thanks to Internet access and social media, salient events can quickly become common knowledge, pressuring authorities to acknowledge what happened—even when they would rather not. Recent protests in Russia are a prime example, with social media and independent news galvanizing more than 100,000 people to take to the streets. Something similar occurred last year in China, when slow acknowledgment of the COVID-19 outbreak in Wuhan temporarily undermined authorities’ legitimacy, especially after Chinese citizens took to social media to share independent information.

Transparency about high-profile events can legitimize an autocrat in citizens’ eyes and on the global stage—but potentially at the expense of domestic control. So how do autocratic leaders strike a balance?

China’s efforts to control information about political violence in Xinjiang demonstrate this balancing act in action. China is often credited with having a long-term strategic perspective, but their handling of information on political violence reveals an addiction to the short-term prioritization of social control.

China’s Transparency Problem

Autocracies like China are widely assumed to be more capable than democracies of depriving militant groups of the “oxygen of publicity” through control of the media, but the reality is more complicated. Authorities no longer remove all the oxygen without severely compromising their legitimacy with an increasingly connected and technologically savvy citizenry.

The tension between transparency and social control can be readily seen in the way Chinese Communist Party (CCP) authorities have approached domestic dissent on the part of Uyghurs, a Muslim minority who live mainly in the north-western region of Xinjiang. Among the 12 million Uyghurs in China, more than 1 million are being held in detention centers, in an effort the US calls genocide. Over the years, there have been various attempts at dissent by the Uyghurs, some of which have been violent, and which China characterizes as “terrorism.”

In the longer term, Chinese leaders stand to benefit from transparency in this context. Acknowledging Uyghur attacks allows China to garner international support by linking incidents to the “global war on terror,” and provides an opportunity to appeal to Han nationalism and bolster legitimacy. But in the shorter term, acknowledging attacks also invites international criticism of human rights practices, raises questions among citizens, and incentivizes further violence.

The question is: Which of these tendencies prevails—transparency or information suppression? Drawing on original, comprehensive data on all known incidents of Uyghur violence, we explore the timing of official coverage in the People’s Daily—the authoritative voice of the CCP. We find that the Chinese government promptly acknowledges violence only when the domestic economy is thriving and China enjoys diplomatic support abroad. In other words, transparency is rare. When international and domestic conditions are anything less than politically ideal, the impulse to control information and enforce stability prevails.

Risks and Rewards of Transparency

The CCP is aware of the positive returns that accompany quick official acknowledgment of negative events. Failures to officially acknowledge high-profile incidents have proven costly. The school collapses in the 2008 Sichuan earthquake, the 2011 high-speed rail accident, and recent events surrounding the COVID-19 outbreak in Wuhan are prominent examples of high-profile events that damaged the reputation of the CCP among Chinese citizens.

By promptly acknowledging Uyghur-initiated political violence, China could shape the narrative and potentially insulate its policies from criticism. Given the advantages, why does China typically obscure information about Uyghur political violence?

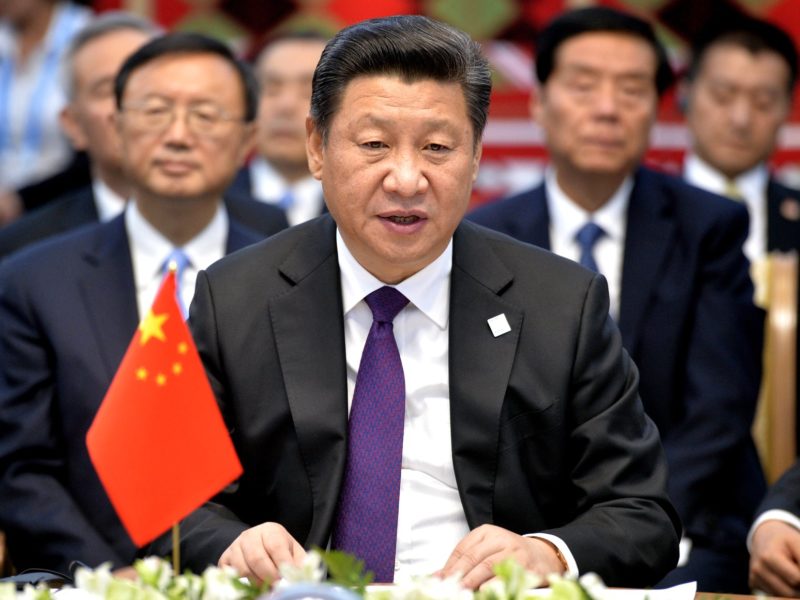

In China, “stability above all else” is a cornerstone of domestic policy, and has become even more so since the rise of Xi Jinping and the increasing personalization of authority that has accompanied his leadership. Transparency is seen as detrimental to that stability. Greenlighting popular discussion and media coverage may intensify ethnic tensions, triggering or seeming to sanction violent reprisals.

International concerns also disincentivize open discussion, particularly since highlighting Uyghur ethnic violence can invite foreign criticism of China’s highly repressive ethnic policies. Although China has leveraged global concerns over militant Islamist movements to frame Uyghur violence as Islamist terrorism, Western suspicion that China hides human rights violations behind the “war on terror” has grown more pronounced as international awareness of the fate of the Uyghur minority has grown.

China’s Bias Toward Caution and Opacity

Legitimacy at home and abroad are long-term priorities for the CCP. Domestic instability and international pressure, however, are more immediate and concerning threats, and fear of instability biases authorities toward silence.

This bias toward caution is fundamental to the Chinese system’s structure and incentives at all levels. Individual bureaucrats fear that poor performance on social stability metrics will block their promotion. For top-level leadership, fear of popular unrest—dating back to the collapse of communist regimes in Eastern Europe and the Tiananmen democracy movement—still lingers. At the same time, China’s emergence from a “century of humiliation” has combined with the increasing personalization of the state under Xi Jinping to produce a profound intolerance of outside criticism. The combination of these forces leads the system to default toward opacity.

The tradeoff between legitimacy and stability is evident beyond China. In autocracies, terrorism that occurs at politically unfavorable times is less likely to be reported, potentially biasing data that relies on local media for evidence of terror attacks. Consequences could range even further: Militants could strategically time attacks to advance their agendas, considering their own tradeoff between extra publicity and the legitimacy of their missions.

International criticism of China’s treatment of the Uyghurs is growing. But the CCP’s penchant for domestic stability and control suggests that international pressure is likely to reduce CCP transparency even more.

Philip B. K. Potter is an Associate Professor and Director of the National Security Policy Center at the University of Virginia. Chen Wang is a PhD candidate in the Politics Department at the University of Virginia. Claire Oto is a Policy Analyst in the National Security Policy Center at the University of Virginia.