Guest post by Jaclyn Johnson and Christopher Faulkner

The Nyiragongo volcano in the North Kivu region of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) has displaced thousands since it erupted last month. The reports out of Goma are nothing short of horrific. Children have been separated from parents with more than 100 missing as of May 25. Moreover, some 450,000 have fled their homes since the start of the year due to conflict. This disaster does not appear to be relenting soon, with the threat of a second eruption and earthquakes rattling the country daily.

On its face, the eruption is a devastating natural disaster, hammering an already grief-stricken region in a country that has experienced decades of protracted armed conflict. However, the eruption of Nyiragongo is an inflection point that signals a looming uptick in violence. What do policymakers and the international community need to know about Nyiragongo’s most recent eruption?

Natural Disasters and Conflict

There is a well-established link between natural disasters and the onset of civil conflict. Specifically, rapid-onset disasters such as earthquakes or volcanic eruptions are significantly associated with an increase in the likelihood of armed conflict. Such instances can increase grievances and exacerbate tensions within society. Not only can this create opportune conditions to challenge the state, but these events can push the state to employ violence as a tool to re-establish control and authority. Additionally, natural disasters, by straining resources and limiting state capacity, can also prolong ongoing war and exacerbate public health crises. While the state distributes resources to recovery efforts, it reduces its ability to counter insurgent threats. When and if the military becomes a critical component of the state’s crisis response, it is less effective in counterinsurgency campaigns. The DRC’s recent “state of siege” demonstrates the potential competing security situation in responding to the most recent eruption. Finally, the infrastructure capacity of the state is reduced by natural disasters, tipping the balance of power in favor of insurgents.

Nyiragongo could spur all three of these links between disaster and increased conflict duration. Goma was economically strained even before Nyiragongo’s recent eruption; the COVID-19 pandemic caused food prices to soar in the region; poverty in Kivu is among the highest in the country. COVID-19 is also impacting the capacity of the state, and the vaccination rate in the DRC is lagging, with less than 0.1 percent of the population vaccinated. As a result, COVID-19 will likely continue to slowly drain state resources from the already limited pool. Any aid that is redirected to crisis response is aid that will not be used to contain rebel groups in this region.

The United Nation’s peacekeeping mission in the DRC, MONUSCO, has had an active presence over the course of the last decade as an intermediary and peacekeeping force between warring factions. However, MONUSCO has redirected its efforts from traditional peacekeeping operations to crisis response. MONUSCO was already drawn away from their original mandate by the COVID-19 pandemic, and are now flying reconnaissance missions to evaluate the likelihood of a second volcanic eruption. This redirection of MONUSCO—from conflict prevention and civilian protection to crisis response—while not unprecedented, will likely provide opportunity and motive for rebel groups to resume their use of ever-escalating, violent tactics. The porous border between the DRC and Rwanda (and other neighboring states) is likely to become even more permeable, easing the movement of illicit weapons, insurgents, and other conflict facilitating materials.

Geography and Conflict

Where the Nyiragongo disaster is occurring within the DRC is also important in assessing its likely impact. Natural disasters in the midst of civil war can dramatically impact rebel group resiliency and strength. While some insurgent groups may be negatively impacted by a natural disaster, others thrive. Notably, insurgent groups that engage in smuggling are more resilient when faced with external shocks like natural disasters. This is particularly concerning news for the Eastern DRC where many groups are known to be engaged in the smuggling of various conflict minerals.

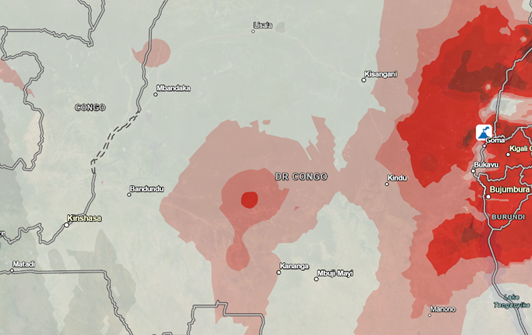

As civilians flee en masse, there will be a dramatic influx of civilians into areas of heavy conflict. The map below illustrates the projected density of violent events using ACLED data since November 2020. As the map demonstrates, if civilians desire to stay within the borders of the DRC, they will almost certainly have to move into the most conflict-prone regions of the state.

Nyiragongo’s last eruption in 2002 left at least 250 killed and over 120,000 homeless. Following that event, thousands of Congolese refugees fled to neighboring Rwanda, many reporting they were met with challenging conditions. Many ultimately made the decision to return home instead of staying in refugee camps—a pattern also emerging with this recent eruption. If history tells us anything, this eruption will have a negative impact on health and human security, especially amid a global pandemic.

Jaclyn Johnson is an independent researcher and instructor at the University of Kentucky. Christopher Faulkner is currently a Visiting Assistant Professor in International Studies at Centre College and an incoming Postdoctoral Fellow in National Security Affairs at the US Naval War College. The views expressed here are solely those of the author and not of the Naval War College, The Department of the Navy, the Department of Defense, or the United States Government.