Guest post by Alex Thurston

Around the world, jihadists use a dizzying array of mechanisms to finance themselves, ranging from oil sales to control of ports. Among other sources of revenue, some jihadists appropriate the Islamic concept of zakat (religiously obligatory alms) as a justification for taxing civilians. What are the advantages of collecting zakat, versus arbitrary taxation systems imposed by conventional rebels? And how are civilians affected by these taxes?

A look at the Islamic State West Africa Province (ISWAP) shows the advantages of zakat for jihadists—and the burden they impose on civilians. Based in northeastern Nigeria, ISWAP broke from Boko Haram in 2016 and eventually outcompeted it. Its relative success is partly based on the group’s claim that it is more benevolent toward civilians than the ultra-violent Boko Haram. ISWAP also inherited a favorable conflict environment: Nigerian security force abuses had alienated many civilians, and authorities abandoned some rural territory to the insurgents, opening the field for ISWAP.

Unlike Boko Haram, whose sources of revenue have been opaque, inconsistent, and predatory—including looting and ransoms—ISWAP collects zakat more systematically. In the Islamic State’s Al-Naba’ bulletin, ISWAP recently claimed that its “Zakat Office” collected approximately $157,000 during Ramadan and the preceding month. This is not a vast sum either in terms of ISWAP’s own operations or in terms of the tens of millions who live around Lake Chad, but neither is it insignificant.

Beyond the obvious financial benefit, the collection of “zakat” appears also to help ISWAP create political bonds with civilians. This isn’t unusual: rebel taxation is often an element of “rebel governance” and “wartime political orders.” Yet zakat is different from arbitrary forms of conventional rebel taxation in that the Islamic textual tradition details zakat’s mechanics, for example regarding herds. Collection of zakat also allows ISWAP to present themselves as justice-minded Muslims to a majority-Muslim local population—though many surely know when ISWAP is bending Islamic textual traditions to suit its whims. This ideological aspect has also been a factor for far richer Islamic State fighters in Syria.

The biggest benefit to ISWAP of collecting “zakat” is political. Jihadists occupy a different niche than conventional rebels within national and international systems. If many conventional rebels aspire to participate in peace deals or power-sharing agreements, such outcomes typically elude jihadists, or do not interest them in the first place. Unable to decisively take power over entire states, jihadists are stuck in “boom-bust cycles.” Attempts to build a “proto-state” elicit military interventions that jihadists cannot withstand. Yet as African jihadists “go rural,” they are not just roving terrorists—they also exercise forms of “decentralized governance.”

Collecting “zakat” represents an attempted solution to the ambiguity of ISWAP’s political position. As Mancur Olson argues, the “stationary bandit” imposes taxes, rather than just confiscating assets. Anticipating long-term rule, the stationary bandit has an incentive to nurture economic growth. But roving bandits, anticipating briefer tenures, may decide to plunder and run. ISWAP is in between those poles, facing significant uncertainty—the now 12-year-old insurgency has no end in sight—but ISWAP cannot count on stability. Limited taxation is the group’s solution for the moment.

How are civilians affected? There’s a lot we don’t yet know about the impact of ISWAP on civilians, but we have some clues.

In Al-Naba’, ISWAP relays that roughly 80 percent of what it collects is from livestock, versus only around 20 percent from crops and cash (the other two main categories of zakat-able assets). Taxing pastoralists suits ISWAP’s present modus operandi—a largely mobile ISWAP can target a largely mobile population, without making itself into a sitting duck.

Redistributing wealth positions ISWAP as a benefactor to the poor. Jihadists, drawing on the Qur’an verse that specifies who can receive zakat, also keep portions for themselves. But despite the theme of justice in Islamic State propaganda, ground realities are grimmer. Al-Naba’ makes little reference to the Lake Chad Basin’s complex humanitarian emergency involving displacement, hunger, and disease. And pastoralists are already suffering as pastures narrow and anti-pastoralist sentiment grows among farmers.

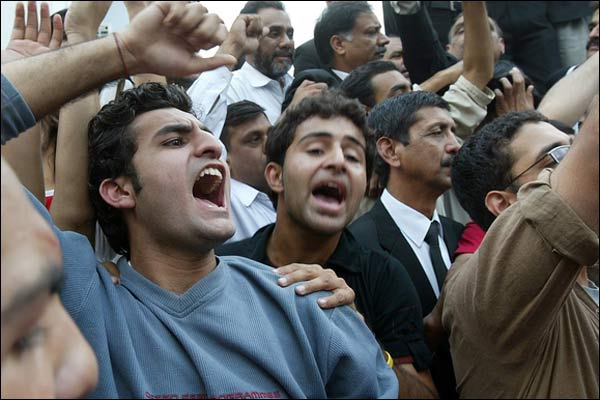

Institutionalized rebel taxation sometimes correlates with some degree of protection for civilians who pay. ISWAP’s relations with civilians reportedly range from cordial to hostile, but in various areas under its control, ISWAP reportedly allows people to conduct business so long as they pay taxes. That report quotes one ISWAP commander as saying, “It would seem that the military, even at the height of their control over these territories, did not present themselves as a value proposition to the villagers, [meting out only] injustice.”

But jihadists’ taxation is not always well received. Islamic source texts detail a system of justice, but texts do not determine how actual interactions unfold between jihadist commanders and individual herders, farmers, or merchants. With jihadist organizations fairly decentralized, multiple units may demand “zakat” from the same community. In western Niger, ISWAP’s allies in the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara are triggering backlash by imposing levels of “zakat” that locals cannot bear.

ISWAP has shown remarkable tenacity, and zakat is one element driving their success. The Nigerian federal government can argue that jihadists like ISWAP are criminals, but taxes often go unpaid even in more secure parts of Nigeria, and the wealthy live lavishly while many citizens face grinding poverty. ISWAP promises (however unrealistically) a different model to what it calls “the infidel, capitalist economic system.” Counteracting their propaganda will require a fundamental shift by West African states, which are themselves often predatory or indifferent toward the poor.

Alex Thurston is Assistant Professor of Political Science at the University of Cincinnati.