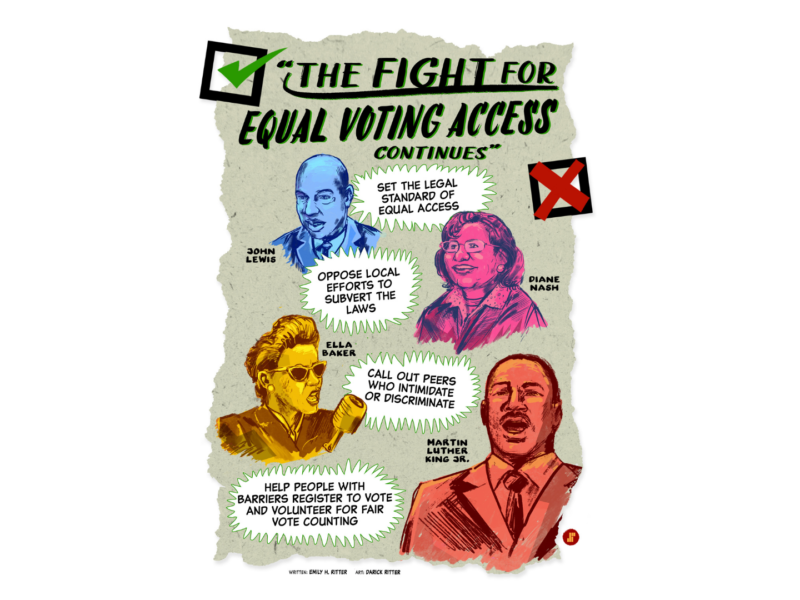

By Emily Hencken Ritter and Sequential Potential

Dr. Martin Luther King spent his adult life fighting without violence for people of color to have equal access to vote in elections in the US. He did so alongside many other brave leaders, like Ralph Abernathy, Ella Baker, John Lewis, Diane Nash, and A. Philip Randolph. The movement culminated in President Lyndon Johnson signing the 1965 Civil Rights Act into law.

King’s fight for equal voting access continued well after 1965, and it continues today, as government policies add requirements and create obstacles to voting and poll watchers intimidate voters. King’s family has decried these efforts and said about Martin Luther King Day that there can be “no celebration without legislation.”

The US needs federal legislation like the Freedom to Vote Act, which would extend the voting franchise, and the John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act, which would re-establish many elements of the original Civil Rights Act. The Senate failed to pass these acts yesterday. But even if senators had moved the bills forward, passing laws isn’t enough. The US must address the federal and local systems and stakeholders who participate in oppression.

Even during the Jim Crow era of discrimination, it was legal under federal law for Black citizens to vote in all elections. But discrimination at a variety of levels made it nearly impossible for Black people to vote in practice.

When legislators pass laws to prevent someone from voting based on race, gender, beliefs, or some other characteristic, or when police prevent someone from entering a polling place, this is repression. Repression is sometimes violent. National leaders create the conditions for repression through laws or the absence of laws, but repression is carried out locally by groups with power, and often by those who control the use of force—police, military, or pro-government militias.

Yet security agents aren’t the only ones who carry out leaders’ preferences for discrimination and control, and national legislators and executives aren’t the only ones who direct or facilitate repression. Jim Crow laws and practices illustrate this perfectly: state and local governments passed ordinances that allowed for poll taxes, literacy tests, and the like; bureaucrats in state and local offices implemented those laws by unequally enforcing them according to race; and citizens enforced these laws and norms with intimidation and even violence against people who tried to register themselves or others to vote.

These layers of repression are vastly understudied in political science—sociologists do a bit better. By studying primarily security agents or criminal justice actors as agents of repression, scholars miss the vast infrastructure and behaviors that create and implement discrimination and harm. In so doing, we fail to understand, explain, predict, and end it.

Luckily, activists tend to have a better understanding than scholars of this complex ecosystem. Movements like the Civil Rights movement and Black Lives Matter, along with non-governmental organizations, tackle the full range of stakeholders and systems that perpetuate repression. Stacey Abrams’ organization Fair Fight brought civil rights lawsuits against Georgia government offices on claims of disenfranchisement. The Tennessee Equity Alliance mobilizes underrepresented voters and draws attention to local and state laws that would discriminate.

Citizens and local bureaucrats are the ones who, ultimately, either carry out repression or fight it. Changing national laws is important but insufficient without addressing this base.

To answer the call of civil rights leaders past and present, people should do much more than march in support of national legislation. They should oppose local efforts to subvert those laws with their voices and votes. They should spread values of equity and equality in their communities, calling out peers who intimidate and discriminate. They should help people who face structural and personal barriers that keep them from the polls to register and vote, and volunteer to ensure fair vote counts.

If the persistent presence of repression is local, so are the solutions.

Text by Emily Hencken Ritter. Images created by Sequential Potential. The words in these images are fictional and written by the post author—not quotations from the persons represented.