By Emily Hencken Ritter and guest contributor Jennifer N. Barnes

On June 24, 2022, the US Supreme Court released a decision in the case of Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization that overturned the precedent of Roe v. Wade, the landmark 1973 decision that protected the right to an abortion. The decision leaves the question of abortion rights up to individual states, with 11 states already making abortion illegal or heavily restricted and another 11 set to do the same soon.

The decision delegates the policy to subnational and private actors, allowing them to be repressors rather than the federal government itself. Criminalizing abortion is a tactic of discriminatory political repression, one that highlights the cooperation between different actors to control women’s lives.

Criminalization of abortion is discriminatory

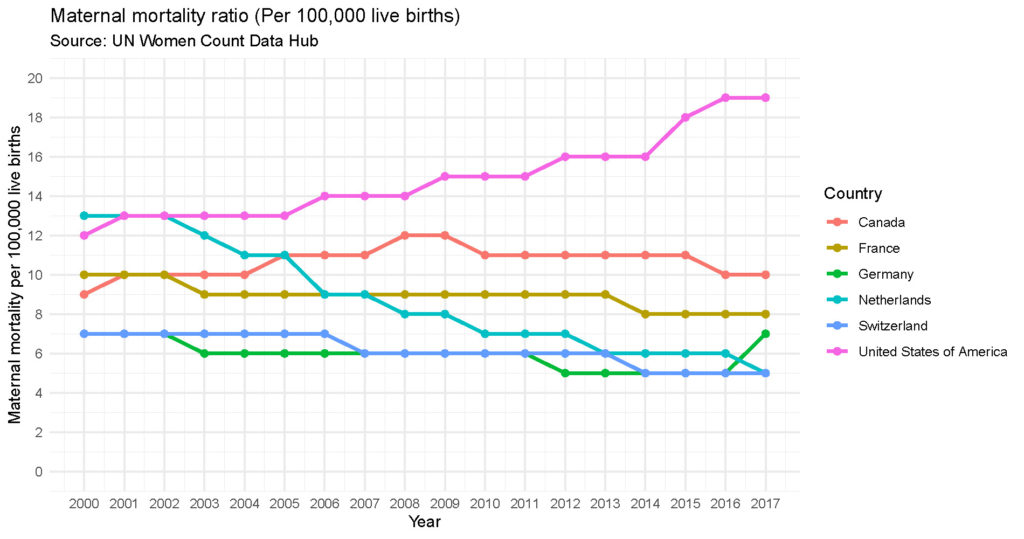

The decision inherently disproportionally affects women and girls. An estimated 73 million induced abortions take place globally each year. Approximately 45 percent occur unsafely, primarily in developing countries. Unsafe abortion is a leading—and entirely preventable—cause of maternal deaths and morbidities worldwide. As shown in the figure below, using data from UNWomen’s Database, the US already leads on maternal mortality among industrialized democracies.

Abortion bans do little to prevent them from occurring. Instead, restricting abortion makes critical contraception and healthcare services more difficult for women—especially poor women—to obtain, or inaccessible altogether, in a country that already underperforms on women’s health relative to other high-income countries.

Abortion bans are considered discrimination under international human rights law. They directly violate numerous rights of women and girls, including the right to life; the right to the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health; the right to benefit from scientific progress and its realization; the right to decide freely and responsibly on the number, spacing and timing of children; and the right to be free from torture, cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment and punishment.

Why would a country that values human rights and equality allow such obvious discrimination and harm? The answer is simple: because some Americans—men and women, authorities and civilians, people at the national and local levels—benefit directly from control over the social and economic prospects of women and girls.

Criminalizing Abortion Is a Tactic of Political Repression

Repression—when governments use violence or other coercive tactics to raise the costs of challenging political power—can take many forms. Often it looks like police using violence against protestors, laws restricting freedom of assembly, or barriers to voting. Repression also takes more subtle forms like discouraging ethnic groups from forming organizations or providing low-quality education to one group compared to another. These more nuanced forms of repression make it difficult for minoritized people to band together and use creative tactics to change their lack of power in society and politics.

Political decisions such as the overturning of Roe v. Wade fall into this second, more subtle category of repression. In making it more difficult to obtain an abortion, many women will endure greater and more lasting trauma from rape, financial burdens for which they have few resources and higher barriers to economic, social, and political advancement. Outlawing abortion will affect women’s ability to obtain higher education and therefore economic advancement. Without control over when and with whom to have a child, women lack control over their economic, social, and political experiences.

Those in favor of restrictive and discriminatory policies benefit from the ability to maintain sexual control, economic control, and power over household outcomes. Men benefit from more freedom, more money, and more power than women, and the authorities whom the dominant group elects to power benefit from their support.

Criminalizing Abortion Is also a Tactic of Societal Repression

In new research, we argue that government actors benefit from and allow private actors to repress women and other minority groups as part of a repressive strategy to collude with members of a dominant social group in order to control and disenfranchise a minoritized group.

In a process we label societal repression, members of a dominant societal group derive social, economic, and political benefits from their position in the social hierarchy (or caste). The dominant social group is dominant because of the power they hold over other groups, not necessarily because they are a majority. Men maintain that position and its economic and social benefits by, first, enforcing the hierarchy against the marginalized group in private spheres, like arranging marriages, restricting girls’ access to education, and committing domestic violence at home, or refusing to hire or fund women in local economies. Second, the dominant group collaborates with government authorities to create policies that allow the violating behaviors to occur without punishment. For their part, government actors remain in political power with the support of the dominant group.

In other words, both government authorities and the dominant group benefit from societal repression, largely because it happens in spaces where governments cannot reach and the public cannot see. Men benefit in social and economic spheres when abortion rights are restricted, and those men vote for leaders who will restrict them. Of course, many women also support abortion bans, and their agreement with the dominant group gives them some access to its power. Indeed, opponents of abortion access often don’t think of their position as being one of strategic repression, instead focusing on questions of morality, but it still has the effect of restructuring who has more power and who has less. Governments disenfranchise and discourage women from participating in society and challenging them politically, continuing male dominance.

It Could Get Worse

In his concurring opinion, Justice Clarence Thomas goes as far as to suggest that the court should, in future cases, also reconsider Griswold (protecting privacy rights related to the use of contraceptives), Lawrence (protecting consensual same-sex sexual activity), and Obergefell (protecting same-sex marriage). In doing so, he connects the logic of the Dobbs decision to other US legal decisions that protect personal and social rights for women and LGBTIA+ persons. If these rollbacks occur, these minoritized groups will lose the gains they have made in the social hierarchy of the United States, with benefits once again accruing to the dominant social group and the government it supports.

Though we often think of repression as direct—like security agents using violence against minorities—women’s rights are violated and controlled most often in the private and social spheres. Government authorities benefit from it and avoid responsibility for it by delegating the discrimination to private actors, as Turkey does with femicide, Pakistan does with girls’ education, and Iceland does with domestic abuse. Women’s rights are violated, and the government keeps its hands officially clean.

Because repression through abortion bans is indirect, putting pressure on the government to change its policies and practices will probably be less effective for improving women’s rights than it is with other, more direct types of repression. With abortion rights now determined sub-nationally, advocates for women’s rights must simultaneously address the front-line repressors—members of the dominant cohort—and the state authorities that make the policies. It’s a two-front battle, but one that affects and marginalizes half the US and global population. That’s a battle worth fighting.

Emily Hencken Ritter is a permanent contributor at PVG, as well as an associate professor at Vanderbilt University. Jennifer N. Barnes is a political science PhD student at Vanderbilt University.