Guest post by Mark Peffley, Marc L. Hutchison, and Michal Shamir

During President Biden’s recent trip to Israel, he reaffirmed the United States’ commitment to a two-state solution to Israel’s conflict with Palestinians living in the territories occupied by Israel since 1967. Biden’s pledge, however, was met with silence from Israel’s prime minister, Yair Lapid. One could hardly blame Lapid. Israel is preparing for its fifth round of elections since 2019. And the opposition to Lapid’s coalition is led by Benjamin Netanyahu, whose right-wing coalition is known for two things: opposing any concessions to the Palestinians to achieve peace, and curbing the democratic freedoms of Israel’s Arab citizens, about 20 percent of Israel’s population.

How did Netanyahu become the longest-serving Israeli prime minister in history and why did political intolerance toward many domestic groups increase during those years? The answer is relevant for democracies everywhere. As we show in our recent article, chronic terrorism increased the Israeli public’s willingness to deny basic liberties to domestic groups alleged to be “fellow travelers” of the perpetrators of violence.

History is littered with examples of threats from war or terrorism stoking public support for repressing domestic groups who pose little objective threat—think about the internment of Japanese-Americans during World War II and the post-9/11 surveillance of American Arabs and Muslims. During the McCarthy era in the US, Samuel Stouffer and others coined the term “fellow travelers” to refer to groups on the left—socialists, atheists, pacifists—who were alleged by anti-communists to be philosophically supportive of communism despite no formal association with the US Communist Party. In our research, we used the term to refer to domestic groups whose sociological makeup—i.e., their national, religious or ethnic background—or political views are alleged to enable or support terrorism. While Stouffer and political scientists have studied political intolerance for many years, our study is the first to show how chronic terror attacks precipitate political intolerance toward several domestic groups alleged to be fellow travelers of the actual perpetrators.

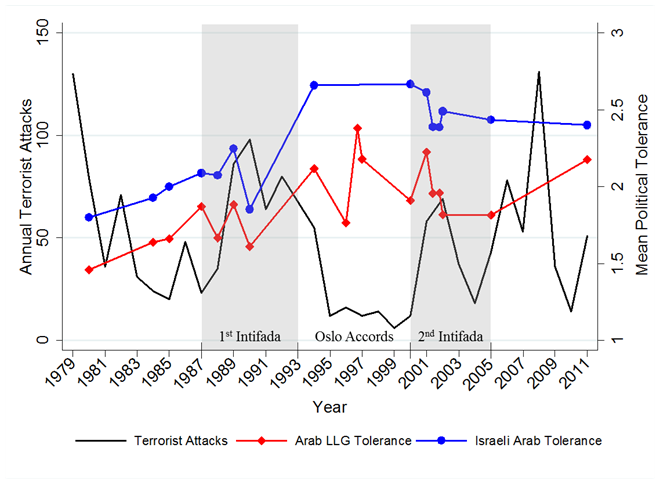

Israel has suffered from chronic terrorism for much of its history, with most of the attacks carried out by Palestinian terrorist groups in the West Bank and Gaza. During the 30-year period covered by our study, from 1980 to 2011, Israel faced close to 1,500 terror attacks (Global Terrorism Database), with two organized terror campaigns bracketing the Oslo Peace Accords. We tracked political tolerance among Israeli Jews during the same period and found that political tolerance toward three groups distant from the actual perpetrators—Israeli Arab political groups (e.g., the Islamic Movement, Balad), Jewish leftist groups (e.g., Peace Now, Meretz), and Arab citizens of Israel—falls precipitously as the number of terror attacks increases (Figure 1).

Our focus is on public support for allowing members of the three fellow traveler groups to demonstrate, which is not only a fundamental democratic liberty but is essential in Israeli because demonstrations are the most common form of political participation by the Arab minority.

But exactly who is intolerant toward whom, and how far does intolerance travel from the actual perpetrators to more distant domestic groups who pose no security risk?

We found that chronic terrorism strengthens the political identities of right-wingers and widens the pool of who they consider to be part of the outgroup—i.e., a group viewed as distinctively different from the ingroup. When the threat is high, a confluence of psychological and political forces blurs outgroup boundaries among rightists, who view their ingroup (“we”) more narrowly and fellow traveler outgroups (“they”) more broadly but with less differentiation. Overall, it is only the Right that reacts to higher levels of terrorism with a diffusion of intolerance toward all three fellow traveler groups. Faced with the same levels of terrorism, Jews in the Center and on the Left do not become more politically intolerant.

In Israel and elsewhere, the diffusion of intolerance has serious consequences for democratic backsliding. In Israel, public support has allowed right-wing governments in power to pass legislation limiting the rights and liberties of Arab parties and Arab citizens. In the words of one observer, the fear of terrorism triggered an impulse among the Right in Israel to “choose identity over democracy.”

Intolerance toward fellow traveler groups is clearly a global concern. The Kurdish citizens of Turkey, Kashmiri citizens of India, and Muslim citizens of many Western countries have all been subjected to increased surveillance and intolerance after attacks by terrorist groups sharing a common ethnic background.

But the diffusion of intolerance toward fellow travelers is not inevitable. Elites play a central role in interpreting “raw” international events like terrorism for the public. Authoritarian leaders from Turkey’s Erdoğan, to India’s Modi, to Hungary’s Orbán stoked fears of terrorism as a pretext for expanding executive powers and diluting or dismantling liberal democracies. Closer to home, the terror attacks of 2015–2017 in the US and Europe prompted right-wing populist presidential candidates Donald Trump (US) and Marine Le Pen (France) to propose sweeping measures targeting the civil liberties of Muslims at home and abroad.

Counterexamples of leadership emphasizing tolerance and democratic values include the Obama administration’s 2015–2016 counter-radicalization strategy of organizing community engagement activities with Muslim groups, George W. Bush’s visit to a mosque to condemn attacks against American Muslims just days after 9/11, and the concerted response of Danish elites to tamp down public fears and intolerance after the Danish “Muhammad cartoon crisis” led to fierce protests by Muslim groups.

In addition to damaging democracy, the repression of fellow travelers can be counterproductive in the fight against terrorism. Students of terrorism point out that an important goal of terrorists is to recruit followers by provoking the government to over-react and lose legitimacy. Other studies show that the intensity of anti-Muslim hostility at the local level in Western Europe was linked to online pro-ISIS radicalization; and that punitive counterterrorism strategies that seriously compromise civil liberties and human rights end up “[hampering] counterterrorism while increasing terrorist activity.”

Mark Peffley is a Professor of Political Science at the University of Kentucky. Marc L. Hutchison is a Professor of Political Science at the University of Rhode Island. Michal Shamir is a Professor of Political Science at Tel Aviv University, Israel.