After Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) agents executed a search warrant at the Florida residence of former president Donald Trump, officials reported threats of political violence against federal law enforcement. A Pennsylvania man was charged after issuing violent online screeds against the FBI. Threats turned to action in Cincinnati, Ohio, as a self-professed Trump supporter attempted to attack the FBI’s local office before being killed in a firefight with police. Reacting to these events, a former New Jersey Attorney General remarked that “extremist rhetoric” from politicians with respect to the FBI would have “real-world consequences” such as escalating violence.

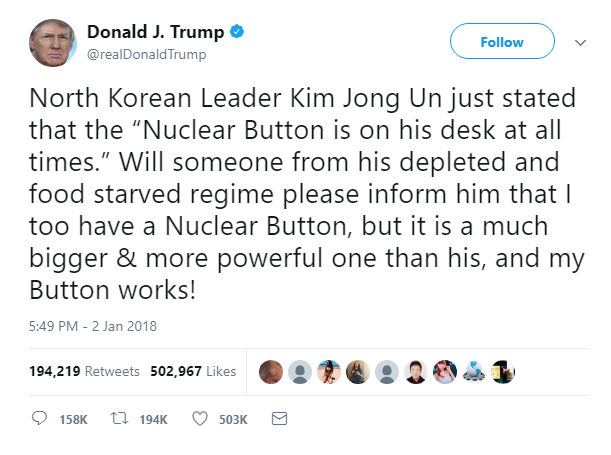

While scholars have studied political extremism and armed groups in the United States—investigating the causes, targets, tactics, organization, and online behavior of extremists—the sophistication of these groups and their ties with politicians have reached a perilous point. During the January 6, 2021 riots against the certification of the 2020 presidential election results, the founder of the extremist group Oath Keepers attempted (unsuccessfully) to contact President Trump. Trump, however, gave only “inspiration” to these groups leading up to January 6, never overtly coordinating with them. David Rapoport characterizes this “intensified” alignment between the Trump administration and extremist groups and the potential for a splintered far-right to “merge into larger movements” as aspects of a new “fifth wave” of modern terrorism.

As the 2022 midterm elections and 2024 presidential campaign approach in the US, what are the implications of violent extremists acting in the name of a politically powerful former—and potentially future—president? Such a situation is unprecedented in recent United States history, but not for another country in the Americas: Argentina. My research looks at what happens when extremists use violence against security forces and political elites to support the comeback of a former president, using evidence from the lead-up to Argentina’s September 1973 elections. Our findings offer insights—and warnings—for the present situation in the United States.

Argentina’s September 1973 elections occurred soon after the country’s return to democracy from military dictatorship. The 1966-1973 right-wing military regime crumbled in part because of unrest among organized labor and students. From these disaffected populations emerged left-wing extremist groups such as the Montoneros and the People’s Revolutionary Army that used terrorist tactics to weaken public support for the military and hasten the return of ex-president Juan Perón, whose political movement had been banned for almost two decades. Perón played a dangerous game with the extremists, using them to aid his return to office and to defeat his nemeses in the military. As historian Luis Romero describes:

“[Perón’s] strategy of confrontation with those who expelled him from power consisted of using the youth, and the popular sectors that they mobilized, to harass his adversaries, and at the same time to present himself as the only one capable of restraining his followers.”

Even after the military dictatorship announced that it would hold elections in which Peronists would be permitted to run—and even after Perón himself laid the groundwork for his September 1973 candidacy—attacks by extremist groups continued. The former president would not formally disavow the groups acting in his name during the campaign, recognizing the political benefit of having them “harass his adversaries.” Bombings, kidnappings, and assaults on military, business, and educational establishments demoralized Perón’s opponents and signaled the outgoing regime’s inability to maintain security.

Perón’s belief that stoking confrontation between his armed supporters and political opponents would pay off was correct. Areas that extremist groups targeted with terrorism in the months leading up to the election shed support for Perón’s military-backed opponents in the Federalist Popular Alliance at a higher rate than other areas, but had no decrease in turnout—suggesting that demoralized right-wing voters sought other political movements not targeted by violence. The ex-president cruised to victory with almost 62 percent of the popular vote.

While the scope and scale of extremist violence in Argentina in 1973 far exceeded events in the United States in 2022, the case offers three lessons for scholars and policymakers.

- Demonstrate resolve: In a confrontation between armed non-state actors and the security community, a firm and consistent response to extremist violence avoids signaling weakness. In Argentina, the military noted that one of the effects of widespread attacks among the public included “alarming signs of disbelief and hopelessness” with respect to politics. As confidence in United States institutions plummets to record lows, a judicious response to attacks on those institutions could avoid making matters worse.

- Respond constitutionally: Security agencies’ response to armed non-state groups can sow the seeds of its own failure. Any actions that violate—or could be plausibly argued to violate—due process protections and First Amendment rights are repression under Christian Davenport’s definition. Repression of these groups and politicians aligned with them, besides being unconstitutional, can backfire and increase public support for the groups if it fails to dismantle their organizing capabilities.

- Reinforce democratic control: Responding to armed non-state groups, no matter the size of the threat posed, brings with it delegation of power and an increase in resources allocated to the security community. Ensuring these agents are accountable to their democratically-elected principals keeps the cure for violent extremism from becoming worse than the disease.