By Sarah Bush and Lauren Prather.

An ongoing FBI investigation is currently trying to determine the nature and extent of Russia’s intervention into the 2016 US election, including whether it involved collusion with people working for the Trump campaign. The House and Senate Intelligence committees are also pursuing the issue.

A recent news report suggests that the Obama administration learned about Russian efforts to influence the election as early as the summer, but some worried that going public with the information before the election would only further Russian goals to undermine confidence in the system.

Did Russia’s meddling affect the public’s views of the election and democracy more generally? To find out, we launched a survey just before the election and then followed up with those same people just after. The survey reached a national sample of more than 1,000 Americans and asked questions about foreign interference in the election, trust in the election, and political participation more generally.

How Democrats and Republicans perceived foreign meddling

One key set of questions related to perceptions of foreign meddling. Specifically, we asked people if they thought other countries influenced the results of the recent election and which countries had the most influence.

Around two-thirds of the people we surveyed both before and after the election perceived at least some foreign meddling. Of those who perceived meddling, 74% said it was Russia who tried to influence the results of the election. In other words, many Americans were attuned to the possibility of Russian interference, even though the most forceful statements about Russia’s meddling by US intelligence officials were made well after the election.

We also wanted to understand not just whether Americans perceived foreign interference, but who in the American public was most aware of this issue. In our survey, we found that perceptions of foreign influence in the election did not vary much by gender, education level, or political interest. In contrast, younger Americans and those with more political knowledge were more likely to perceive foreign influence than older Americans and those with less political knowledge. Voters were also less likely to perceive foreign influence than non-voters.

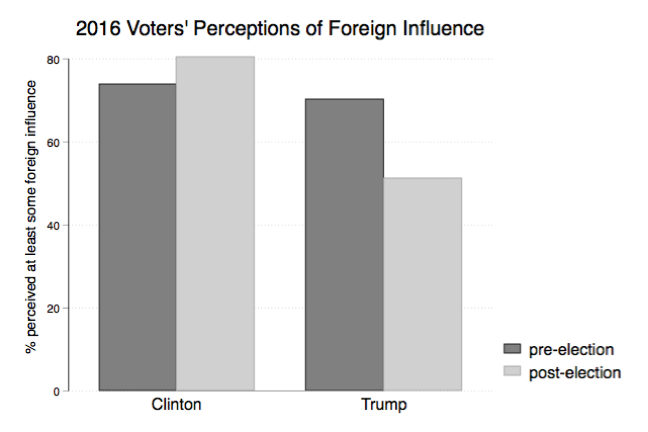

The largest differences in perceptions of foreign influence were between Trump and Clinton voters – but only after the election. As the figure shows, both Trump and Clinton voters perceived similar levels of influence before the election, but their perceptions changed after the election. Before the election, Trump and Clinton voters were equally likely to perceive some foreign influence (73% of Clinton voters vs. 70% of Trump voters). Their attitudes changed dramatically after the election, when 80% of Clinton voters perceived some foreign influence in contrast to only 51% of Trump voters. This drop among Trump voters may be a response to the president’s questioning of Russian interference in the election. Months into the Trump administration, the president’s supporters have repeated his uncertainty about whether Russia was responsible and downplayed the hacking’s importance for the election outcome.

How foreign meddling undermines trust in elections

In March 2017 testimony to the House Intelligence Committee, former FBI Director James Comey stated that a goal of Russian meddling in the US election was to undermine Americans’ trust in their democratic institutions. He said, “One of the lessons they may draw from this is that they were successful because they introduced chaos and division and discord and sowed doubt about the nature of this amazing country of ours and our democratic process.”

To shed light on that possibility, we asked Americans how much they trusted the outcome of the election after the results were announced. We asked people to place themselves on a scale from 0 to 10, with 0 meaning no trust in the election result and 10 meaning absolute trust in the result. Most Americans trusted the election result, with an average response of around 7.

However, when people perceived foreign meddling, their trust in the election was lower. For people who did not perceive foreign meddling, their average trust in the election was at 8.2 on the 10-point scale. Among people who perceived some meddling, this number dropped to 6.5. This finding is correlational, which is to say that we don’t know that perceptions about meddling caused people to have less trust in the election.

That said, the difference is not simply a result of partisanship. Although there was a difference in perceptions of meddling across Clinton and Trump voters, the effect of perceived meddling on trust in the election was the same for both groups: individuals who suspected meddling in the election trusted the outcome of the election less. The average trust for Clinton voters dropped from 7.2 to 6.1 when they perceived meddling, and the average for Trump voters dropped from 8.7 to 7.9 when they perceived meddling.

Why trust in elections matters

Many scholars have noted that trust in election results is related to whether people participate in politics, including whether they vote in elections. This pattern holds in both the United States and other countries. Our survey found a similar relationship between Americans’ trust in the 2016 election and their intentions to participate in politics in the next five years through voting and other means.

As we argue in recently published research in the Journal of Politics, perceptions about election credibility matter. That study examined perceptions of election credibility in Tunisia, a new democracy where an election lacking in credibility could have undermined not only democracy but also peace and stability. Like Americans, Tunisians’ perceptions about election credibility were rooted in their information about the election but were also shaped by partisan biases.

The extent of Russian interference in the US election is still under investigation. However, across party lines, perceptions of foreign meddling have been associated with less trust in the election, and that relationship underscores one way that foreign meddling can harm American democracy.

Since harming American democracy was the likely goal of foreign interference, Americans should prepare for future elections to feature even more foreign interventions. It is incumbent upon elected officials to agree upon an appropriate response to such meddling and to take pro-active steps to protect our democratic institutions moving forward.

Sarah Bush is an Assistant Professor of Political Science at Temple University and a regular contributor at PV@Glance. Lauren Prather is an Assistant Professor of Political Science in the School of Global Policy and Strategy at the University of California, San Diego.

2 comments

Would be good if Americans and Europeans develop some protecting measures together.

This is a fascinating study, since as far as I know no primary evidence, much less proof, of Russian intervention in the 2016 election has been offered to the public. General belief in the intervention has been entirely a media production and might as well be entirely a fable. I have no trouble believing in the possibility of such things — I imagine states and other important actors try to affect foreign elections when they perceive an interest in doing so — but in this particular case the solid facts have been few, if not non-existent. Which casts an interesting light on public perceptions, and poses obvious problems for doing anything practical about the alleged interventions.