Guest Post by Jared Oestman

In a recent Politico op-ed urging Congress to consider the importance of United States foreign aid programs, Admiral Mike Mullen (Ret.) and General James Jones (Ret.) insisted that “[s]trategic development assistance is not charity; it is an essential, modern tool of U.S. national security.” The authors focus particularly on the importance of this tool in countering violent extremism in distant regions.

With the advent of the “Global War on Terror” directed at al-Qaeda and its affiliates, the United States has developed a pattern of increasing aid funds to countries that experience any terrorist activity that poses a clear threat to its security. This has led to increasing concern among activists that the United States has taken a turn away from targeting development related goals to focus more on using foreign aid to strengthen the military capabilities of recipient governments. Such a shift presents a potential problem as aid aimed at activating an immediate counterterrorism response is often allocated directly to the recipient government with low accountability for how those funds are used.

This concern over the militarization of aid is reminiscent of the United States’ prioritization of foreign assistance during the Cold War to achieve its military and political goals over those related to the development needs of recipients. When the United States’ interests were fixed on countering its Cold War rival the country was less willing to drawback funds from leaders who were strategically important but failed to pursue economic reform. Foreign assistance to such countries was generally ineffective at promoting growth until after the Cold War when the United States could credibly enforce its aid conditions.

Still, until recently, little scholarly work identified the extent to which the United States’ foreign aid strategy has again shifted from focusing on development to privilege the military. This is a task that Tobias Heinrich, Carla Martinez Machain, and I set out to accomplish in a recent publication.

Our findings reveal that increases of both military and non-military aid occur in response to terrorist activity carried out by groups with ties to al-Qaeda. More specifically, we show that countries that experience attacks by al-Qaeda affiliates receive increased proportions of military aid while their surrounding neighborhood only notices a significant increase in aid earmarked for development and civil society.

Indeed, foreign aid has played a significant role in accomplishing the counterterrorism goals of the United States in the current century. Through programs administered by USAID, the State Department, and the DOD, the United States has channeled large sums of aid to countries in which terrorist groups are located. Such funds not only target the security sector but also aim to improve the recipient state’s levels of education, health and civil society. Foreign aid can effectively reduce terrorism that originates from the recipient state when targeted in such a comprehensive manner, namely by undermining terrorist recruitment. Moreover, donor countries may use foreign aid to strategically purchase cooperation over counterterrorism policy from the recipient government.

Still, to what extent are allocations of development aid directed or replaced by the security interests of the United States? We propose that when a terrorist group with ties to al-Qaeda resides and carries out attacks within a state, higher levels of both military and non-military aid will be allocated by the United States to that state. Moreover, since recruitment efforts, attacks, and the basing of al-Qaeda affiliates tend to transcend state boundaries, the amount of aid channeled to the surrounding neighborhood should also increase.

To test whether these expected patterns of foreign aid allocations hold, we set our focus on the region of sub-Saharan Africa, an area that draws strong development concerns from the international community. Utilizing available data for 46 countries for the years 1996 to 2011, we find that, in general, military and development aid respond in different ways to al-Qaeda sponsored terrorist attacks.

When at least one attack, or an increase of attacks, occurs within a country, the United States responds by increasing its flow of both military and non-military forms of assistance to that country. In contrast, we do not find that military aid directed to neighboring states increases in response to the occurrence of acts of terrorism. Instead, these states only experience increases in civil society and development aid in reaction to terrorist attacks.

Given that military aid allocations increase for targeted states but not their neighbors, it is likely that the United States relies on the law enforcement powers entrusted to the executive branch of the targeted state to ramp up their counterterrorism capabilities and respond with crackdowns immediately following attacks. Provisions of military assistance are often aimed at ensuring cooperation over such efforts. In contrast, the more preventive-oriented development aid that is expected to make populations less vulnerable to terrorist recruitment is provided to both the targets of the attack and neighboring states.

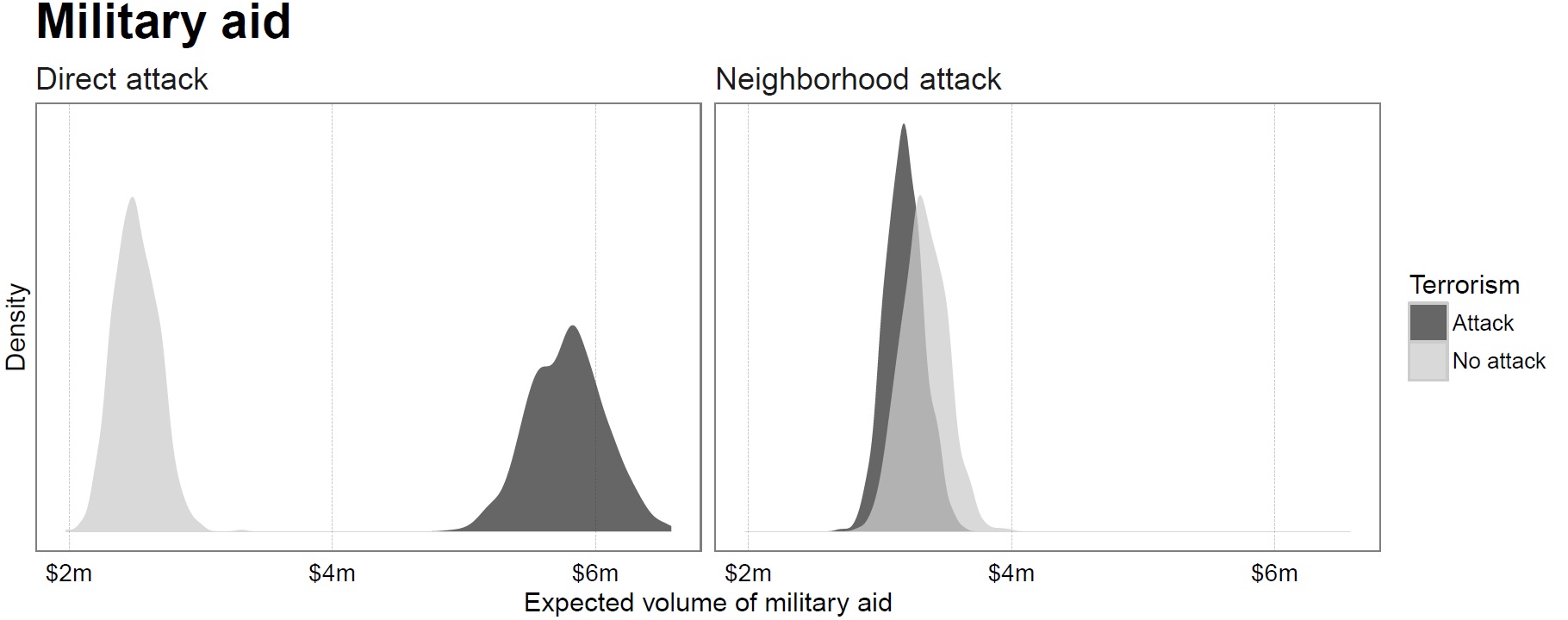

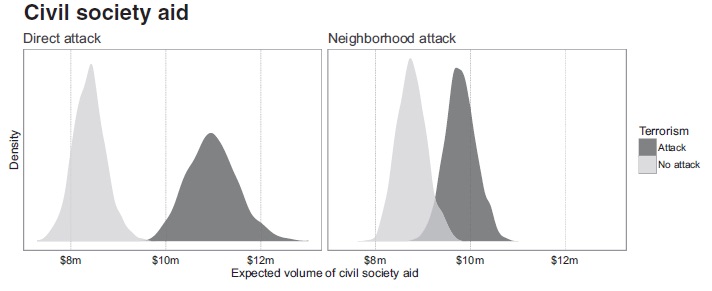

The figures below show the difference in the expected amount of military and civil society aid for a typical recipient country and its neighborhood when no terrorist attack occurs and when at least one attack occurs. The average increase of military aid that goes directly to a country that experiences a terrorist attack is 3.3 million USD whereas military aid to neighboring states does not change. In contrast, the expected increase of civil society aid that goes directly to states that experience an attack is 2.6 million USD while a typical neighboring state also notices an increase of 1.0 million USD (note that we also look at development aid separately and identify significant increases). While these changes reveal that the United States responds to terrorist activity by increasing aid, we wanted to further identify whether aid funds are more likely to become “militarized.”

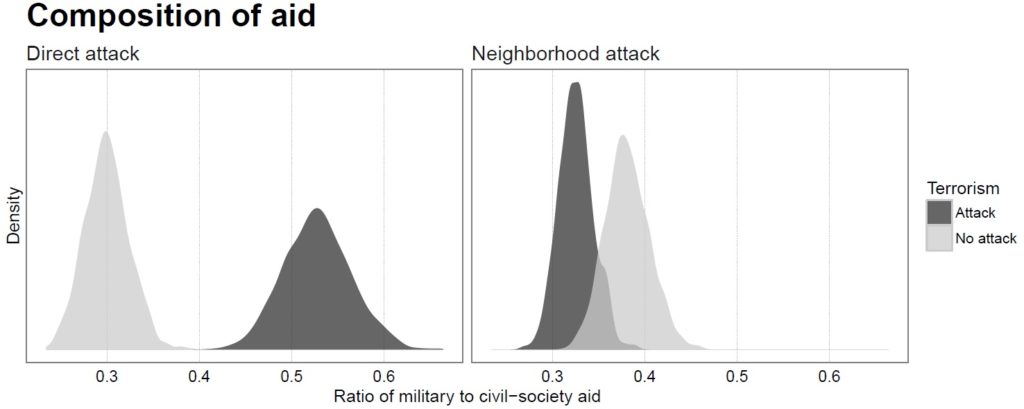

To gain a better understanding of this, we compared the ratios of the expected levels of military and civil society aid when an attack does and does not occur in a typical country and its neighborhood. By comparing these ratios, we see that when an attack occurs within a country, though both types increase, the average level of change in military aid is greater than the change in development aid. We do not find that the same is true for states that are in the same neighborhood but that are not attacked directly.

The figure below depicts this finding. The ratio of military to civil society aid to countries that experience a direct attack increases from 0.3 to 0.5 while little change occurs in the ratio of these funds to neighboring states.

Does this evidence lend support to advocates’ concerns that United States foreign aid has become militarized? We conclude that foreign aid is clearly used by the United States as a tool for counterterrorism in sub-Saharan Africa. The composition of aid provided to states that experience at least one terrorist attack directly on their soil favors the military. However, this is not the case for the surrounding neighborhood. Moreover, the United States also increases its allocations of civil society and development aid to the entire neighborhood.

These patterns are likely driven by a comprehensive effort to undermine terrorist recruitment activity with the aim of contributing to the security and economic development of recipient states as well as promoting good governance and civil society. Future research should work to further identify whether aid serves as an effective counterterrorism tool and the potential consequences of this policy approach.

Jared Oestman is a PhD student in the Department of Political Science at Rice University. He is interested in conflict, foreign policy, and peacekeeping.