Guest Post by Tim Wegenast and Gerald Schneider

Angola’s capital Luanda is considered to be the most expensive city in the world. While oil rents make luxury condos and yachts affordable to a tiny minority of businessmen and politicians, most people live in squalor. The paradoxical combination of resource wealth and pervasive poverty, familiar to social scientists as the “resource curse”, is omnipresent across African states. Oil in Angola and Nigeria, coltan in the Democratic Republic of Congo, iron ore in Guinea, gold in South Africa and Ghana, uranium in Niger or diamonds in Zimbabwe contribute to enduring poverty, inequality, corruption, weak institutions and conflict within these countries.

Multinational oil and mining companies are often accused of complicity in plundering the nation’s immense wealth and fostering local conflict. In his new book, Tom Burgis, a longtime African correspondent of the Financial Times, describes a network of multinationals, anonymous corporate investors and bankers who make nontransparent deals with coup leaders and ominous African elites, allowing the siphoning out of the continent’s natural resources. The author notes that “just 2.5 percent of the $41 billion that the mining industry generated in Congo flowed into the country’s meager budget.”

Multinational oil or mining firms have a bad reputation worldwide and there are numerous examples on how the resource extraction by international investors creates local communal grievances. Media and NGO reports describe how these companies degrade the environment or how they undermine the social fabric around mines and oil fields. However, almost no research has systematically analyzed whether international resource-extracting firms systematically produce more social conflict than domestic, state-owned companies.

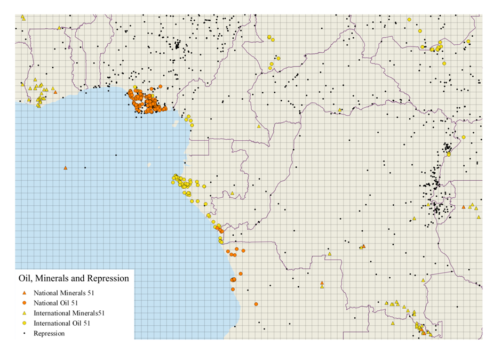

In a recent study, we examine how control rights of oil and minerals affect social dissent within Sub-Sahara Africa. We thereby rely on the occurrence of state repression as an indirect indicator of resentment among local communities. This follows the logic that repression is the government’s answer to quell protests prompted by internationally-controlled resource extraction. International oil companies (IOCs) have for instance been accused of complicity in human rights abuses and repression in countries such as Nigeria or Sudan.

We show that multinational oil corporations are linked to more state repression compared to domestic, state-controlled firms. This is especially the case if these firms operate in an uncertain legal and political environment. There is, however, only weak indication that gold and diamond mines operated by international investors have the same detrimental consequences.

The following figure illustrates how we conducted our study and how we are able to link government repression to extraction sites. To conduct our study, we compared whether GIS grid cells with or without a particular resource ownership arrangement experienced state repression or not. The usage of such highly disaggregated data is increasingly used to study economic development and a variety of other social outcomes.

There are several reasons why internationally-controlled hydrocarbon productions triggers social dissent. First, a foreign company is often less inclined to cover the environmental or social costs of resource extraction if the state is unable to regulate these activities effectively. Second, multinationals do often not know whether the governments of the host countries will respect the exploration licenses in the long term. The fear of expropriation drives them to extract as much as possible in the shortest amount of time. State-owned companies often face longer time horizons and might therefore have higher incentives to engage in stakeholder dialogues with local communities. Third, the social corporate responsibility codices, which have become a standard tool for multinational companies, face higher hurdles in the extraction industry. International mining and oil companies consequently adjust their social responsibility practices to the level of corruption and the regulatory capacity of host countries. Bribing local officials in order to obtain drilling licenses seems common practice. Once operations start, IOCs are hardly compelled to maintain good relationships with affected local communities. Finally, unlike private companies that seek profit maximization, national oil corporations often pursue non-commercial goals such as the provision of infrastructure or public goods and employ more workers in order to buy-off political support.

Our evidence qualifies the so-called “resource curse.” The findings described in our article stress that it is important to consider how states regulate the access to their natural resources and under what institutional environment resource extraction is pursued.

Tim Wegenast is a post-doctoral researcher at the University of Konstanz. He has published widely on the relationship between resource extraction, intrastate conflict and local development. Other research interests include long-term consequences of climate change and the role of religion in explaining social unrest.

Gerald Schneider is professor of international politics at the University of Konstanz, editor of European Union Politics and co-editor of International Interactions. His main areas of research are European Union decision making and the eoncomic causes and consequences of violent conflict.