By Oliver Kaplan for Denver Dialogues.

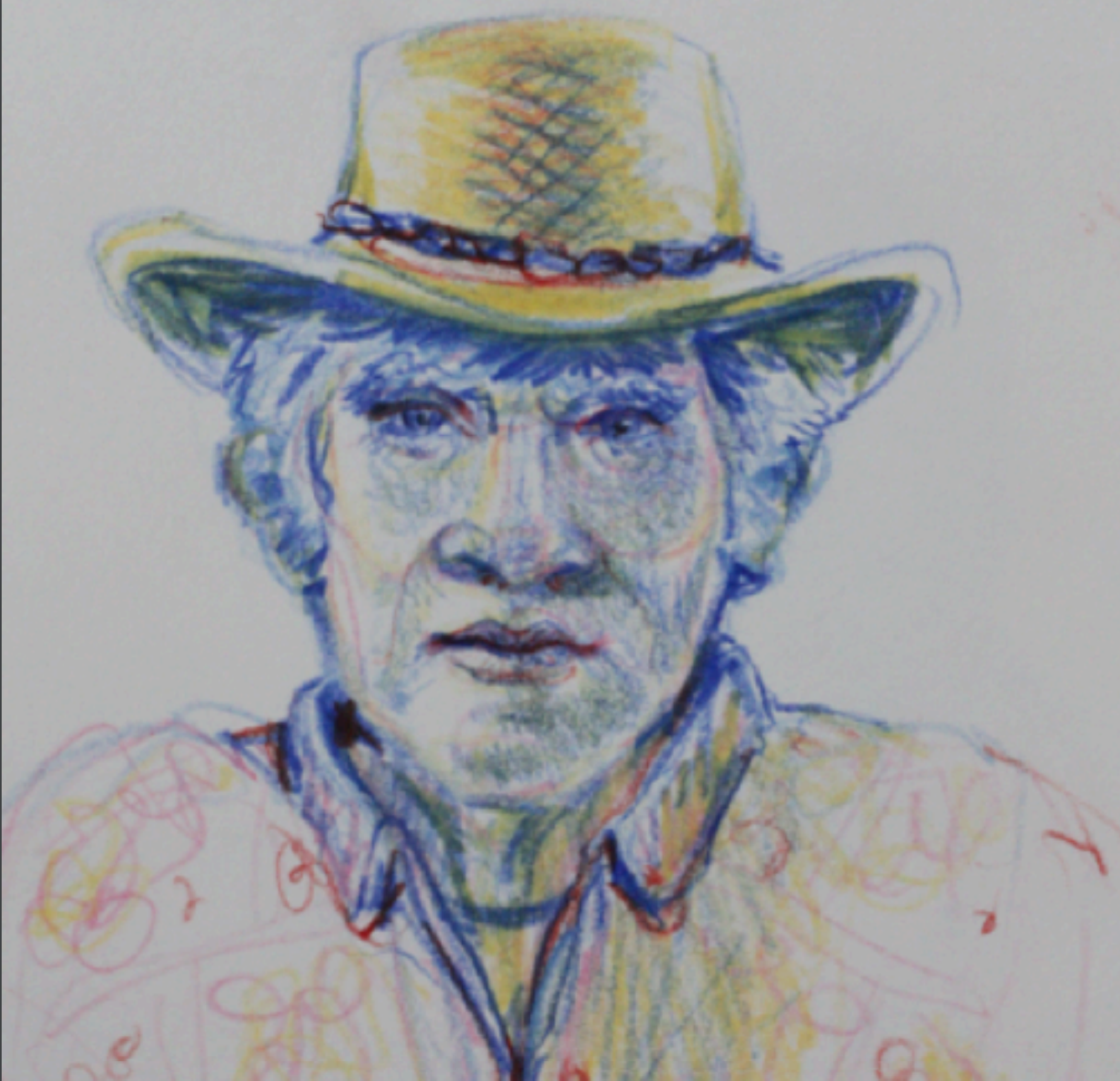

The news came via a friend’s Facebook post earlier this year. A key informant that I had spent time with a decade earlier during my field research on community peace movements had passed away.

When I heard the news, I paused a moment. I was taken aback. At first, I felt remorse. I had hoped to see him again after my fieldwork wrapped-up, but hadn’t gotten to. I reflected on how he was a good man—buena gente—who persevered through turbulent times to help bring peace to his community, and was suddenly no longer with us. I felt an unexpected wave of emotions. Mainly, I felt sad, and missed him, like it was a friend. But there was also more of a mix given our unique relationship. I noticed the urge to check myself, to not feel too much, “I’m a dispassionate political scientist, after all.” What was I going through? I couldn’t put my finger on it (is there a German word for it?!). Then I realized it: I was feeling key informant loss.

There are various professional, transactional, or non-familial relationships where we still experience loss. “Doctor loss.” “Therapist loss.” And certainly others. The researcher-informant relationship, as a professional interaction, is like these relationships in some ways, but is also distinct. Our informants may appear in our lives for only fleeting moments, but they help us with our projects by sharing their insights (in theory for some greater good). At least for that, we are deeply indebted to them. But they also often help in many more ways.

When one is out in the field in isolated areas for extended periods, alone, far from friends and family, these informants—these people—can’t help but become friends and family (how many Godchildren have you taken on?!). This is especially the case in risky conflict settings where one can’t go safely alone, and where those locals’ knowledge and instinct is indispensable and protective. The connection is also simply a product of sharing daily life: dancing, playing, attending church and birthdays and funerals, and other events that don’t cease just because of fieldwork. They become far more than a key quote or data point in a spreadsheet.

The key informant-researcher relationship is an interesting one because it is a kind of give-and-take, a dialogue, but is also bound by rules and norms of fairness and distancing. By the nature of research topics, researchers and informants may share some commitments and interests, and perhaps have natural affinities because of that. Yet researchers, from their perch, and informants, with their lived experiences, don’t always share the same incentives, motivations, power, or privilege in the interaction. And, true to the scientific method that is drilled into us during graduate training, we are taught to think of research as removed, dispassionate, and sterile (and you can almost hear the research ethics board admonishments: “Don’t get too close! Don’t create unreasonable expectations of reciprocity! No favoritism!”).

Meeting informants generates some dilemmas—questions that were in the back of my mind during my research that I could only later articulate: Do I get close? Do I attach to these informants, these people? Do I keep in touch with them, and how? I haven’t quite resolved these ethically-laden questions for myself yet (and certainly each researcher has to for her/his own).

But then there’s the unavoidable human connection. That’s what happened when I was in the campo (countryside), with lots of downtime and just hanging out and shooting the breeze (in plastic chairs, of course) between spurts of “data collection,” or sometimes just waiting for interesting things to happen. People take you under their wings, they’re excited you’re there, and want to share their lives with you, even if they have no particular reason to. And you share back…

In the process of coming to terms with my key informant loss, I accepted that it’s okay to feel. To be emotional. To care about these people (this in turn raised the question of what emotional duties do we have toward these informants? And are the relationships perhaps easier to manage after a project’s rigors have concluded?). All is to say these contradictions made fieldwork a more intriguing navigation than I first expected.

So, here’s to you, key informants, who have helped us all, shared your valuable time, and even offered friendship to awkward outsiders when you never had to. Thank you. And Rest in Peace.

Oliver Kaplan is the author of Resisting War: How Communities Protect Themselves.

1 comment

Dear Oliver,

thanks for sharing this with us.

I think it fits well into the whole range of emotions that we (peace practitioneers) develop towards our foreign partners: The local activists who endure and act in a situation that we only visit.

And I don’t think there is a German word for it. MITLEID in the meaning of suffering together with the directly affected person (not to be confsued with “bemitleiden” (to pity someone)) may fit to some aspects.

Otherwise we would speak of “die kleine LEERE, die jemand hinterlässt”, e.g. the empty spot within our selves that a deceased person leaves behind.) This “Leere” (emptyness?) can then be thoroughly described…